Editor’s Note: As we approach our tenth year of publishing Fiction Writers Review, we’ve decided to curate a series of “From the Archives” posts that we’ll re-publish each week or so during the year. Some of these features are editor favorites, some tie in with a new book out from an author whose work we’ve covered in the past, and some are first conversations with debut authors who are now household names.

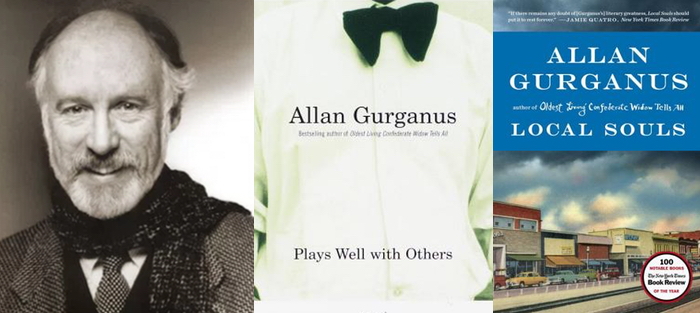

This week we’ve returned to Dana Kletter’s interview with Allan Gurganus, published originally on May 25 of 2010.

After a very New York childhood and adolescence, I was reluctantly transplanted to North Carolina. Though I thought no good could come of this, I flourished. I loved the south. New York friends could not understand my affinity for this place they believed to be primitive and hostile, and so I used to hand out copies of Eudora Welty’s Why I Live At The P.O. in an effort to explain. Now I am just as likely to refer folks to Allan Gurganus’ collection White People, because what is so irresistible about the south partly has to do with language, with words and stories. As Gurganus said in an interview published on identitytheory.com, “You would be a crazy person not to be rejoicing everyday to have been born in the south. The sheer density of narrative, the sheer capacity for telling amusing stories, not just by people that are paid to write, but people who are earning a living in service stations and who amuse themselves…”

In his most famous novel, Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All, as well as in his novel-in-progress, An Erotic History of a Southern Baptist Church, Gurganus is at once compassionate and critical as he explores the people, communities, and culture of this problematic region, his home. His stories put me in mind of the ethnographic phrase “thick description,” anthropologist Clifford Geertz’s term for concentrated depictions based on observation through which eloquent interpretations of a culture can be made.

I sat down with Allan in November [of 2009] when he was visiting Ann Arbor as the University of Michigan MFA program’s Zell Distinguished Writer in Residence.

Interview:

Dana Kletter: To prepare for your reading, and this interview, I found myself rereading your collection White People, which brought to mind Clifford Geertz’s phrase “thick description,” and this quote by him on the meaning of culture:

Man is an animal suspended in webs of significance he himself has spun. I take culture to be those webs, and the analysis of it to be therefore not an experimental science in search of law, but an interpretive one in search of meaning.

Allan Gurganus: Well, I was taught to write about what I knew and white people seemed to be all I knew anything about, if that. I studied color theory in art school, and black is defined as the presence of all colors, and white is defined as the absence of all colors, and I look at my skin and I see that I’m pink or wheat colored or brown and I realize that our Caucasian race has been in charge of Western Civilization for thousands of years. How weird and typical that we would name ourselves for the absence of all color, for a vacuum. It is an assertion of Calvinism, of self-loathing, of fear of sensuality and sexuality. And the very phrase “white people” just strikes me, always, as kind of hilarious. And so I tried to see what that definition would mean on the basis of the stories that I’d written and tried to shape the collection around that concept. I went back in the galleys and put the word white in every story and tried to hook it into a kind of train that held together as a unit, as well as separate stories.

So, there was a kind of epiphanic realization about whiteness? Was that before you assembled the collection?

I’ve loved that title and that title has been in my book of titles for many years. I had saved it back and that seemed the perfect book for it. And then I found in writing “Blessed Assurance,” which is one of the later things I wrote, that it seemed to add another element to what you were talking about before—that definition of culture, ethnography. I think we could all…every tribe could write all of world literature about its own posse, its own traits. But the fact that white people have been in charge of the culture for so long is a way of diagnosing what’s right and wrong with the culture, and why those webs you talk about can seem so claustrophobic and disappointing ultimately.

I’ve loved that title and that title has been in my book of titles for many years. I had saved it back and that seemed the perfect book for it. And then I found in writing “Blessed Assurance,” which is one of the later things I wrote, that it seemed to add another element to what you were talking about before—that definition of culture, ethnography. I think we could all…every tribe could write all of world literature about its own posse, its own traits. But the fact that white people have been in charge of the culture for so long is a way of diagnosing what’s right and wrong with the culture, and why those webs you talk about can seem so claustrophobic and disappointing ultimately.

In addition to fiction, you write political essays, columns in the New York Times, etc. And you have been an out gay writer since your first story was published. There’s a lot of political pathologizing of sexuality, getting louder as the issue of gay marriage becomes a matter of referendum. What are your thoughts on this? Is there a way for literature to play a part in gay rights?

I’ve been both edified at the progress that the culture has made around the issue of gay rights, and disappointed at the same time. I feel there is this glass ceiling, as there was a glass ceiling for women’s advancement, for gay rights. There’s a kind of tacit agreement that, okay, it’s not good to throw beer bottles out of passing cars at two guys holding hands and yell “faggot” and so forth, but when it comes to granting full and equal rights to a gay couple I think we still have some great distance to go. And that is where leadership comes in. I mean, Obama said he would be a fierce defender—that’s a direct quote—of gay rights, and here’s the Maine referendum, which I think could have benefited immensely from a single sentence of support and of fierce defense from him.

I’ve tried to exercise as much patience as possible. It is not that I have a male bride I’m waiting to marry, but I think that it is a simple way of talking about the whole collective experience and I can’t imagine that if Polish Americans were allowed every right in America except the right to marry other Polish Americans that there wouldn’t be riots in the street. And the patience with which we’ve treated our exclusion boggles the mind, just as the patience that African Americans have exercised in not burning down the whole bloody enterprise is just miraculous and shows you what faith in God can really do for people.

So I’m waiting and watching and hoping and trying to content myself with the advances that have been made, but never resting. And really never being casual about just how bigoted people really are about this issue. I don’t understand it. I’m only interested in the people that I’m interested in. It’s not like I’m on the street hitting on married men and children. What harm am I doing? And yet I think the word “sex” in homosexual is the biggest problem. The best sex in the minds of most Americans is the least mentioned and the least visible. It’s why, after genealogy, porn is the biggest enterprise on the Web, because people can do it in the privacy of their home and feel the communication underground with everybody else and be reassured that there are four trillion sites that will minister to their every whim about foots and boobs and animals. But let two men stand up and say I love you in public and they’re shamed and pilloried. Something is sick and wrong.

So it is moving but it is not moving fast enough for me, and I don’t think I’m going to see in my lifetime the kind of progress I’d hoped would be made. On the other hand, I think things have changed. If only for the younger generation. Kids don’t seem to care—straight, gay, bi-, what’s his story?—in that kind of user-friendly neutral judgment kind of way. I’m very heartened by that.

In contemporary high school television dramas and movies there’s a stock gay character, which would never have been true when we were growing up.

Isn’t it beautiful how it has happened?

Is there a role for literature in this? I was thinking about an interview I read in which you said something about James Joyce making the novel safe for sex.

Well, I think the natural course of literature will be that the great romantic novel can be written about a relationship between two women or two men. Not a pathologized investigation or expose. But that is how we will know that something major has been achieved, when the story of two men who fall in love and spend forty years with each other is considered dramatic and interesting and credible. Because that is the heterosexual romance—my one and only, house, home, kids, dog, car. It is hard to just will that into action, just say I’m going to write a happy love story between two gay guys. It has the feel of poster, it has the feel of political coercion. But I do think that is coming and it is something I really look forward to.

You were part of a Bloomsbury symposium at Duke last year, and Bloomsbury was a place where sexual orientation was fluid. When you said “romance” before, I thought of E.M. Forster’s Maurice. What is your interest in Bloomsbury? I mean literary, obviously, but is it also an interest because these were people who were allowed to be overtly, sexually, what they were, whatever they were?

Well, it helped to be the children of the ruling class of England. [Laughter.] Working people have less confidence and less assurance that if they are busted in a men’s room that mama or daddy will get them out. But I think there is something magical about this pan-sexual connection in which married Maynard Keynes is pursuing the boys that Strachey is after and Virginia Woolf is admiring, and Harold Nicholson is pursuing the fathers while Vita Sackville West is after their mothers. There’s something very romper room about that license to operate. And yet here’s E.M. Forster—who is, I think, one of the great writers of the 20th century; I think Howard’s End is one of the books I would save from the fire, highly influential—here’s the liberated guy with the sinecure at a university, celebrated as a novelist, who couldn’t publish the novel that he secreted in his bottom drawer because his reputation would have been ruined. At least according to his own Edwardian lights. There’s something so sad about that, that he hit that glass ceiling in his own life, his own sense of possibilities, and he couldn’t proceed. Now all the sales proceeds of that book are given to gay causes, and that’s fantastic, but think what he might have written if he had given himself permission to let that go and just be himself and wrote.

One of the paradoxes of coming out is that everybody knows you’re gay from the time you’re born. When I finally came out to my parents, very late in their lives, they just sort of forced me to, and I thought, “Oh God, do we really have to go through this drama?” They said, concurrently, “We’ve always known you were gay” and “How dare you do this to us.” Gee willikers, which of these am I to believe? And if you have had forty years to get used to this idea, couldn’t you be a little kinder to me, in that I’ve tried to be kind to you? But there’s this appetite for punishment that is unaccountable, it is one of these things about human beings. When I think about Forster just dithering his last thirty-five, forty years away it just breaks my heart.

Or A.E. Houseman, writing his encoded poems. When I was a child I read things that made me feel my existence was justified. I found myself in them. It’s how you become a writer, I think. You first find yourself in someone else’s writing.

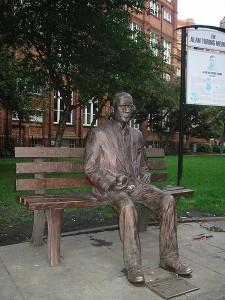

Alan Turing memorial statue in Sackville Park, Manchester

Absolutely. But the taboo. Here’s Alan Turing, who broke the enigma code that essentially let England beat the Nazis, but because he had a male lover who was slightly underage, the police prosecuted him and he wound up committing suicide on account of it. It is only in the last six months that England has finally come out and tried to reverse that conviction. But it is a little late for him. That’s what you want—not any sort of special exemption, just what equal rights means. It is just the opportunity to proceed with your life without having to crimp the hose or tie yourself in knots or put pins in your skin or beat yourself up over something that you have no control over.

What are you working on now?

I’m finishing a collection of stories and novellas I’ve tentatively titled Assisted Living, which are the things I’ve published in the last six or seven years. And a lot of unpublished material because novellas are so hard to place in magazines. I’m also working on a novel that is a companion piece to Oldest Living Confederate Widow, called The Erotic History of the Southern Baptist Church, speaking of getting sex out there. [Laughter.] That’s been in the works for many, many years, but I’ve been actively working on it in this incarnation for about a year and a half or so. It has been kind of joyful because I grew up in a religious household. My father was a born again Baptist, my mother was a Unitarian Universalist who moved south and went to Presbyterian Church as the closest substitute she could find, and my brothers and I were bartered souls being shunted between these two denominations. The Presbyterian side won, thank God, but I’m fascinated by extreme stances, religious and moral. And how those stances tend to engender extraordinary erotic feelings. The more you suppress Eros, of course, as we know, the more rampant it truly is. And so it a fascinating opportunity to go back into American history (the novel starts about 1870) and trace these lines and try to figure out what went wrong with American religion and how it ties to the Calvinist roots.

Will it be a companion piece in the same way that Home is to Gilead

Will it be a companion piece in the same way that Home is to Gilead

Not quite that literal, though some of the characters walk in and out of each book. It is set in the same town—about three miles out of the town, at an old Baptist church. But I’m beginning to feel that I have this sort of Google Earth Weather Satellite vision of the whole community, and it is wonderful, very comforting. When I’m insomniac I can walk from the church to the town and know what’s on the way. It is not based on a lived landscape, but a dreamed landscape, so it is very real to me.

A dreamed landscape…did you dream it? Or create it?

Created and then became a landscape in dreams. It is partly based on how far my grandfather’s farm was from town. And I’m sure it is based on seeing a million country churches, and visiting some. But I’m fascinated with the geography of a small town, how much city ways mean in a town of 3,000 people in 1900. And how they look down on the country people who bring their shoes in tissue paper and put them on just down the city limits and try to blend in. It is very powerful, for me especially, given the complexities of our current world—in terms of communication and just being exposed politically—to go back in time, say, to 1888, and create a farm with no telegraph poles, where if a man wants to go see another man he either walks or rides a horse.

And for me it slows down the hectic rate of invention that we’ve learned to move at. It gets me in touch with an individual soul to state the simplest needs of a story and to play it out on a kind of puppet stage, on a kind of sparser scale, that’s elegant as a horizon with these vertical figures in front. To lift them out of the chaos that I’m feeling in our world as it is now. You know, people are so divided against themselves and each other. And the paradox of communication is that the more things you have to answer in the course of a day, the less you really know. By the time you take your vitamins and return your emails and phone calls and Skype messages, there’s very little left. It is like being perpetually at the far side of a ping pong table and trying to keep the balls coming back over. So for me to inhabit the 19th century is a beautiful balm, a great comfort. It is kind of a laboratory for me, in which I take issues from the 20th century and I trot them back.

I realize that I was born in 1947, that I was born three years nearer the 19th century than this century, and my allegiance—my real nationality—is 19th century. I don’t feel akin to what’s going on. And I guess this is how they get you ready to die. [Laughter.] I’ve heard so many people my age and older say we were so lucky to have fallen in history when we did because we got the best of a kind of 20th century stability growing up after the war, and getting the comfort of returned GIs providing for their children, then getting to rebel against that after our teeth had been straightened. And then being wild and crazy, which some of us actually got to live through too. So I do feel I’ve lived through a particularly blessed period of human history. But my daydreams, my insomniac reveries, are really set in the 19th century.

I once interviewed Cynthia Ozick and she said that while she was writing Heir to the Glimmering World, she kept Forster’s A Passage To India on her desk as a talisman. Do you have a talismanic book you are keeping on your desk?

Well, the one volume that has been most useful is the 1888 Sears Roebuck catalogue. It’s fantastic. And they reprint them, it’s not an original copy. You can get it for $7.00 on line and it is 650 pages thick. If you want baby shoes, I’ve got the first, second and third best pair. It lets you see everything—what would do and what was considered chic. It is full of heartbreaking testimonial letters. “Dear Sirs, That $2.50 Sunday suit you sent me sure looks like a $3.50 Sunday suit.” The description of the hats takes about half a page because there are just so many doodads and gewgaws on them. You could order wagons and horseshoes.

Well, the one volume that has been most useful is the 1888 Sears Roebuck catalogue. It’s fantastic. And they reprint them, it’s not an original copy. You can get it for $7.00 on line and it is 650 pages thick. If you want baby shoes, I’ve got the first, second and third best pair. It lets you see everything—what would do and what was considered chic. It is full of heartbreaking testimonial letters. “Dear Sirs, That $2.50 Sunday suit you sent me sure looks like a $3.50 Sunday suit.” The description of the hats takes about half a page because there are just so many doodads and gewgaws on them. You could order wagons and horseshoes.

And houses too, right?

Exactly. They’d come on the train. In two days you’ve got a new house. And good houses, too; they are still standing. So literarily my model is Middlemarch, which I think is just everything a novel should be. And One Hundred Years of Solitude is a great, great book that I consult. I had a great blinding insight about how to use preexisting books to create a new book. I bought a brand new copy of Middlemarch and One Hundred Years of Solitude and then I started the first chapter of my novel. I worked until I couldn’t work anymore, and then I read the first chapter of Marquez’s novel about community, and then I went back to mine. And then I read the second chapter of Eliot and then went back and worked on mine. And then the second chapter of Marquez and then back to mine. And it was as if I had created a stream that was flowing between two very different shores and that the minerals of each bank were leaching into mine, liquid essence at the center of the book, conforming and shaping. It is a very beautiful experience. I’m fascinated with how reading can be used not just as a source of information or even a source of generally inspiration, but as a shaping force in the creation of fiction.

Is this the first time you’ve consciously used this as a technique?

It is. It just sort of developed. I just thought, you know, what should I do? Because I reread both and they’re both very much about villages. They’re very, very different kinds of books, but with roughly the same number of characters and a lot of connections.

I feel like that is something I learned to do when I was in the MFA program here, to be ignited by another author’s prose, to use those prose to guide and inspire your own.

To be able to use other literature for that, it is so exciting.

What are your thoughts about MFA programs? There’s lots of talk about them being “bad” for your writing. I know you went to the venerable Iowa Writers’ Workshop

Well, it’s hard to argue with anything that gives you two years to write. And I guess I’m a believer, because I’m going back to Iowa to teach in January for a semester. I’ve always promised Connie Brothers—who has been second in command since I was a student—that I would come back and teach, and so this seemed like the perfect time to do it. I’m really looking forward to it. I’ve enjoyed reading the student work here at Michigan. Very talented. I can think of a million things to say to students, among that I’m looking forward to talking to them, but also I really just want to check in with what people that age find to be interesting and important, right now. That’s a great asset, a great tool for me.

Beyond the MFA, into the writing life, how do you maintain, persist, protect and nourish your writing?

Well, I don’t read the Times Book Review every week. I just do my work. That’s the secret. I didn’t publish my first book until I was forty-two, even though I started publishing when I was twenty-five. I’m in no hurry, as long as I have a house to live in and enough to eat. I’m very patient with the work, and I don’t want to show work until I think it’s really got something going in it that’s kicking and essential. I look at the people who publish a book a year, and it’s mostly junk. You can have a baby every ten months, but just because you can doesn’t mean you should. What you risk is becoming a brand name, and some of the people who started publishing when I started have done exactly that. They literally hire people to write their books for them, and then they go out on tour, which seems to me the wrong way to do it. I’m all for staying home and writing and sending anyone else on tour.

Well, I don’t read the Times Book Review every week. I just do my work. That’s the secret. I didn’t publish my first book until I was forty-two, even though I started publishing when I was twenty-five. I’m in no hurry, as long as I have a house to live in and enough to eat. I’m very patient with the work, and I don’t want to show work until I think it’s really got something going in it that’s kicking and essential. I look at the people who publish a book a year, and it’s mostly junk. You can have a baby every ten months, but just because you can doesn’t mean you should. What you risk is becoming a brand name, and some of the people who started publishing when I started have done exactly that. They literally hire people to write their books for them, and then they go out on tour, which seems to me the wrong way to do it. I’m all for staying home and writing and sending anyone else on tour.

I was lucky in that I was published in magazines, I had a readership, and people saw what I was trying to do. But I have this great respect for what a book should be and it hasn’t changed. I want it to be important and significant, as the great books have been to me. It is a way of repaying a huge debt. People say that a novelist is just born at forty, only when you are forty have you had enough heartache and enough death in your foreground first of all to know that you’re mortal. That’s the basic drivers’ license for being a writer: I too will die. And I think about that a lot. It is very hard to know that. But until you are forty or fifty or sixty, you can believe that you and Jesus Christ might be the two holdouts. But I think that to live to be forty is to realize that you are part of a community, that you’re flawed, that you have certain talents and you lack certain others, and it is to know how much you want to work, how much you want to tell. That has to be preeminent.

I’ve taught some extremely gifted students, but the ones who have gone on to have careers as writers are often the ones who have less inherent ability and more will and more need to tell the stories. The most talented student I ever taught wound up writing code in Silicon Valley, and as far as I know has a perfectly happy life. But it is that will, that need to get up and do it every day, that is the governing droit d’état. I look at people of my generation or the younger generation who got a huge amount of attention early, in their 20s for instance, and it has just maimed them. They’ve stayed Johnny one notes; they’ve stayed party boys or wunderkind. And I think it is better to have waited until you have some vision that includes not just you as first person singular, but “we.” That’s the movement of human life—from the singular to the plural. And making your own story big enough and useful enough to include everybody else.

Marilynne Robinson is a very good argument for that: not many books, but all of them important, particularly for writers. You wrote about Housekeeping in a New York Times book blog.

Marilynne Robinson is a very good argument for that: not many books, but all of them important, particularly for writers. You wrote about Housekeeping in a New York Times book blog.

An amazing book.

In particular, you talked about the names of the triangle of female characters: Sylvie, Ruth, and Lucille. The way Sylvie captures the wildness and strangeness of her characters, “the woods come indoors only briefly”; and Lucille as “light, with all its truth-tellings; and Ruth, named for her, “that Biblical paragon.” How are you naming the characters in your new book?

I have certain names that I’ve carried around with me forever. I have journals and I save titles and phrases and character names. Sometimes I have to create a character to go under a name. The preacher, the faith healing preacher I’m writing about now, is named Dicy Pilker. I just love to say it. I can’t even remember making it up. It is as if I found it. It has a kind of inevitability. The name shouldn’t be completely on the nose about the meaning of the character, it should be slightly askew so that you could miss the larger meaning. But I love naming. I think that’s how Adam became the possessor of the Garden of Eden, when he was allowed to name the animals and became responsible to and for them at that moment. I always admire when I’m reading someone else’s book and the names are completely perfect.

That is something that I actually love about the south. I knew a woman in North Carolina named Zora Byrd Fish.

Oh, my god. That is a poem.

I do feel like naming your characters is part art, part magic. I’m not sure how it works.

It is an incantation. Sometimes you have to look through the phonebook. Sometimes you just overhear somebody called something. That’s magical.

What activities in your life stimulate or feed into your writing. Teaching? Gardening? Political activism?

Gardening is a joy because I believe in a kind of rangy English gardening that makes order look like natural spilling generosity. And the beauty of working where I live, where my garden is, is that I can go out between paragraphs and weed or clip or cut back and not commit language so that I am still on the page. Political activism sounds kind of dreary when you say it like that, but everything I do in the community, including an open house that I have every year at Halloween for the neighborhood kids and anybody who wants to come, is political theater, though it is sometimes more deeply disguised than others. Last year the election fell just after Halloween, so we had an occasion to have an Obama character and McCain and a twenty-one-year-old boy dressed as Cindy McCain. And we lost three or four Republicans, but it was my house and my candy and they can come and go as they like. But I like to think that I’ve shaped the minds of sixteen years of children in this town of five-thousand people, who know that somebody is crazy enough to put on this pageant for no money, and is willing to be foolish and dress up and to open up his house to anybody who walks in. And whose biases as a storyteller and as voter as a citizen are on display. The theme this year was healthcare—of course nothing could be scarier—so I showed an insured person and an uninsured person with the same disease at comic extremes. Kids are much smarter than a lot of people think they are; they really pick up on what’s going on. So something as simple as having this once a year for all these years I think has made a difference to the kids in the neighborhood. I know this from people who have stopped by and talked to me.

So it is not that it is any less fun for not being political, it is much more fun for having these encoded messages. And I’d like to think my work has some of those too. One of the things I’m happiest about is that “Blessed Assurance” is now required reading for the ethics course at Harvard Business School, so to whom am I accountable? It is a big question.

Your novel Plays Well With Others was an act of commemoration and remembering, and to me that is political also.

Your novel Plays Well With Others was an act of commemoration and remembering, and to me that is political also.

Absolutely. And one reason writers create characters is in order to defend them, and defense is inherently political. And it is why there are no great Republican novelists—it is because you have to come to the rescue of your babies. And I don’t think Tom Wolfe is a great novelist. Everything I do in terms of shopping, conversations with checkout people, my relation to the Mexican-American family that helps me paint my house or clean my house periodically and their citizenship, is something I’m very involved with. In a way everything is artistic, and in a way everything is political. It is foolish to do too much separating between the two because they both give energy and a forward thrust to the work, if that can be translated.

But you don’t want to be didactic?

There’s a place for that, and thank God there are people who are perpetually on guard, and I appreciate and respect them, but I want to be a painter not a poster maker, that’s the goal.

And how does teaching feed your writing?

Teaching is for me very profound. One reason I don’t teach all the time is, I think, I haven’t really found the balance between writing and teaching. When I’m teaching I wake up in the middle of the night thinking, you know, “I have to tell her about Henry Green and I have to lead him to Isaac Babel and the adverbs only at the beginning and not at the end.” You know how it is, Dana. It’s parenthood times forty, but it is parenthood in a kind of intellectual or spiritual way—you’re guiding them or guarding them much more than they know. If you are a good parent, the kids don’t really understand how much you love them or how much you are concerned for them or it would drive them mad or make them hate you. But I can remember certain decisions I made in teaching twenty-five years ago, certain connections I made for students, with students, in terms of sending them to books. I had a student at Sara Lawrence who was a very talented comic writer, and I sent her to Donleavy’s The Ginger Man and it led her to correspond with him and then visit and they’ve become inseparable friends. And she’s in Ireland all the time, making a film about him, and it is kind of great because I’ve never met him, but those are the kinds of moments when you know that you really made a connection and a correct assumption about another person.

Teaching is for me very profound. One reason I don’t teach all the time is, I think, I haven’t really found the balance between writing and teaching. When I’m teaching I wake up in the middle of the night thinking, you know, “I have to tell her about Henry Green and I have to lead him to Isaac Babel and the adverbs only at the beginning and not at the end.” You know how it is, Dana. It’s parenthood times forty, but it is parenthood in a kind of intellectual or spiritual way—you’re guiding them or guarding them much more than they know. If you are a good parent, the kids don’t really understand how much you love them or how much you are concerned for them or it would drive them mad or make them hate you. But I can remember certain decisions I made in teaching twenty-five years ago, certain connections I made for students, with students, in terms of sending them to books. I had a student at Sara Lawrence who was a very talented comic writer, and I sent her to Donleavy’s The Ginger Man and it led her to correspond with him and then visit and they’ve become inseparable friends. And she’s in Ireland all the time, making a film about him, and it is kind of great because I’ve never met him, but those are the kinds of moments when you know that you really made a connection and a correct assumption about another person.

And just as sex is a subject that must not be talked about, the role of teaching is a subject that should be talked about much more directly, and it is typical of the culture that artists and teachers are disrespected so completely. Only when the artist has made a certain amount of money are they worth discussing. I make very much the connection between writing a book and having a class you teach graduate, or these tireless teachers who year after year put on four shows with high school students and all the mishegas that goes with that.

Teaching creative writing and composition is part of the MFA program at Michigan. I think all of us struggled with that balance, and I do think it has to do with loving your students, but is there a way to be a good teacher without loving your students?

You can’t be the kind of person who doesn’t love them, but to do that completely is to risk sacrificing your work, which is not a fair trade in the long run. I’ve seen this with teachers of mine who published one book and then got stopped by the teaching. They wind up really hating the talented students and doing damage to them, and that’s a horrible, horrible condition. If that power goes wrong it is like they turn into a super villain who was maimed and fell into the acid and is getting revenge. It is terrible.

What’s the most important thing to teach your students? What have you learned from teaching them?

More and more I think about reading and the role of reading and the relation of writing and reading. It sounds like the most obvious thing in the world, but it is something that is assumed or left out. More and more for me it is reading nonfiction—reading straight history, and reading books about science, brain chemistry, things that are just beyond my reach, but which I find very, very exciting and inspiring to try to hold on to. I don’t have the technical terminology, but I’m smart enough to hold onto the movement of the book while it is happening and to see the implications, and I think that is important—not just poets reading poets and novelists reading novelists, but to be grazing in the world, reading newspapers, reading things online, exciting yourself about the world, just keeping fresh to what’s happening. I just wish I had four hours extra every day to read.