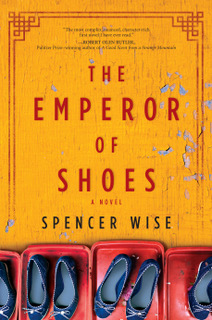

The protagonist of Spencer Wise’s debut novel, The Emperor of Shoes (HarperCollins/Hanover Square Press), is Alex Cohen, a twenty-six year-old Jewish Bostonian in the process of reluctantly taking over his father’s shoe factory in the Chinese province of Guangdong. The narrative charts the the clash and tenuous merger of Chinese and American business culture, and its storyworld features an international community of seekers—looking for money, power, justice, or some combination thereof—who converge on the factory town of Foshan.

The place is prosperous for the owners of its factories and for mayor Gang Xioadan, the rising Chinese star in business/politics who runs the city like a bribe-taking feudal lord. But Foshan is not quite so prosperous for the people who work in the factory, and caring about that fact is how Alex gets himself into trouble. He falls in love with a line worker named Ivy, a woman who’s deeply involved in the workers’ rights movement, and becomes increasingly sympathetic to her cause over time. As Alex gets deeper into the situation he’s made for himself, he ends up pulling himself into a new identity that we—and he—would not have thought himself capable of at the novel’s outset.

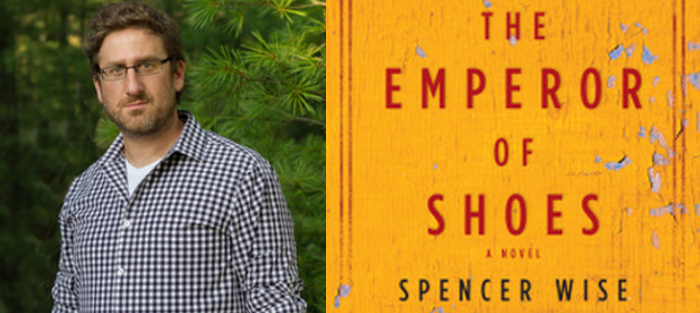

Wise himself comes from a shoemaking family that traces its roots to pre-Holocaust Poland. His work has appeared in such venues as Narrative Magazine, Gulf Coast, The Cincinnati Review, The Literary Review, and The New Ohio Review. He earned his Ph.D. in creative writing from Florida State University and is an assistant professor at Augusta University in Georgia. We talked via email while he toured with his debut novel and settled into his new academic gig.

Interview:

Steven Wingate: The author bio for The Emperor of Shoes says that your family has been in the shoe business for five generations and that you’ve worked in a factory in China. It would appear there’s some overlap between autobiography and fiction here, so I’ll lead off with one of my favorite questions: What deal(s) did you make with autobiography in writing this novel?

Spencer Wise: We both had Robert Olen Butler as a teacher, and one of the many enlightening things he told me was to write from my white-hot center. It sounds new-agey, but it got me to face things in my writing that I’d been ducking for a long time. For one, I’m tremendously proud of my ancestors’ success as Jewish immigrants, shoemakers, in America; but I also find it troubling that Jewish people, who have been persecuted for millennia, would turn around and exploit migrant Chinese workers for a buck. That’s part of my legacy too. As much as the beauty and craftsmanship and hard work of shoemaking. I think I felt ashamed about writing about this because I didn’t want to come across as ungrateful or anti-Jewish (both of which I’ve been accused of now!). Jewishness, as far as I understand it, which admittedly isn’t all that well, has always championed questioning above all else. The Talmud, for instance, that ancient text, is thousands of years of questions. When can we open the oven on the Sabbath? Do we open it with our left or right hand? Do we wash our hands afterwards? On and on and on. It’s sort of hilarious in that regard. It’s a whole religion of questions. So it’s ironic that when I questioned the moral and ethical position of Jews in global capitalism some people said, Whoa, buddy, don’t ask that.

Anyhow, the other white-hot center of the book is the matter of standing up for something you believe in. Personal responsibility. In a world where you can make a thousand excuses for all your shitty behavior or non-behavior, as is often the case, when do you stand up? For what? Now Nike has recently commoditized this message in their exploitative commercial about Colin Kaepernick’s role in the #blacklivesmatter movement. But Nike is good at profiting off a social movement. I mean, let’s not kid ourselves, where do you think Nike’s shoes are made? Same factories my book takes you into. You think Nike cares at all about the social message behind the Kaepernick decision to kneel for the anthem? Sales went up something like 30% after the release of the commercial. So no, that’s harnessing a trendy ideology to drive profit. If Nike wanted to stand up for something they believed in, which they don’t, they would stop making their shoes in China (or Vietnam or India) under the conditions that you can read about it my book. And it would cost them a ton of money. And then they’d know what Kaepernick is going through. So it’s utter hypocrisy. All of which is to say, I was interested in the question, which I think is both Jewish and American, of when do you need to take personal responsibility for changing the imperfections of the world around you. When do you stand up?

Anyhow, the other white-hot center of the book is the matter of standing up for something you believe in. Personal responsibility. In a world where you can make a thousand excuses for all your shitty behavior or non-behavior, as is often the case, when do you stand up? For what? Now Nike has recently commoditized this message in their exploitative commercial about Colin Kaepernick’s role in the #blacklivesmatter movement. But Nike is good at profiting off a social movement. I mean, let’s not kid ourselves, where do you think Nike’s shoes are made? Same factories my book takes you into. You think Nike cares at all about the social message behind the Kaepernick decision to kneel for the anthem? Sales went up something like 30% after the release of the commercial. So no, that’s harnessing a trendy ideology to drive profit. If Nike wanted to stand up for something they believed in, which they don’t, they would stop making their shoes in China (or Vietnam or India) under the conditions that you can read about it my book. And it would cost them a ton of money. And then they’d know what Kaepernick is going through. So it’s utter hypocrisy. All of which is to say, I was interested in the question, which I think is both Jewish and American, of when do you need to take personal responsibility for changing the imperfections of the world around you. When do you stand up?

So let’s go back to your question about writing autobiographically. Nothing in this book happened to me personally except that I traveled to the places I wrote about. I went to Ivy’s village but I didn’t go there with anyone like Ivy, or do anything you read about in that scene. I’ve been to the tannery in Taishan, but I wasn’t there to deliver bribes to a corrupt owner. I visited places, took tons of notes, and stayed open to the possibilities of what could happen in each place to my characters. All the shoe stuff is true. All the details about China are true. But my Dad is nothing like Fedor. I was scared to show my Dad the book, because I thought he would disown me. But I guess we see what we want to see because when he did read the book, I think he focused on the way it celebrated and vindicated his life’s work and the artistry of shoe design and his own genius. He felt like a hero. Which is great. The critique of global capitalism didn’t resonate as strongly with him. Thank God.

I can’t tell you how much time he spent with me explaining the shoe business and shoe making. So one of the most fun parts of writing this book was spending so much time with my Dad, learning about the family business that I bailed on to become a writer. He supported that too—my decision to bag the business and become a poor writer. So he’s a great guy. Fedor is neurotic and funny like my Dad, but he’s much more ethically questionable.

Emperor strikes me as a novel about capitalism—both its history and its current “late phase” incarnation. There’s a clashing/blending of the world’s two most powerful business cultures (American and Chinese) that shows up throughout the book. Fedor is a true believer in the American approach to business, and he’s counterbalanced by Gang on the Chinese side. Yet in the China you portray, there’s a sense of futility about capitalism among the young. As Alex says “No one believes you anymore when you say their time will come.” Could you rap for a bit about the role of capitalism in the book?

Well, that line, “your time will come,” is how a lot of business people from wealthy developed countries in positions of power and privilege justify the exploitation of workers from less developed nations. Suffering becomes a necessary rite of passage, right? The country needs to graduate through the various stages of capitalism—from the smog-ridden polluted industrial phase to the hi-tech, white collar stage. This is all bullshit to me. I’m not an economist by any means, so take my opinion with a grain of salt, but to me this is just a lame rationalization to help people sleep at night. It’s along the same lines as, “Well, we’re giving them jobs! They should be thankful they have a job!” There’s this fantasy that all the migrant laborers are one day going to be living in middle-class comfort and sending their kids to college. Is that what’s happening here in America to migrant laborers? I don’t think so.

Meanwhile, the factory owners are socking away millions in off-shore accounts and sending their kids to Oxford University. And, given the number of young Chinese people I talked to, there’s only so many flat-screen TVs and pieces of Ikea furniture one can amass before they start craving true freedom and justice. I think we’re seeing the same thing here in the States. If you go to Wharton, I’m sure they make capitalism seem like a tidy continuum from third-world (which is a racist and colonialist term) to first-world. And in the first-world what happens? Trump? This? What’s going on right now in America? This sucks. So in the novel I’m driving at the idea that justice and freedom don’t wait. It’s not, well, you need to suffer just a little more and then things are going to be peachy in fifty years. No. That was the rationale for colonialism and you can see the wreckage that left behind. So yes, you’re totally right, it’s a novel about capitalism (amongst other things) and it questions this notion that our systems of governance and economics are somehow inviolable and handed down from Moses. They’re only ideas and policies. Ideas and policies can change.

Meanwhile, the factory owners are socking away millions in off-shore accounts and sending their kids to Oxford University. And, given the number of young Chinese people I talked to, there’s only so many flat-screen TVs and pieces of Ikea furniture one can amass before they start craving true freedom and justice. I think we’re seeing the same thing here in the States. If you go to Wharton, I’m sure they make capitalism seem like a tidy continuum from third-world (which is a racist and colonialist term) to first-world. And in the first-world what happens? Trump? This? What’s going on right now in America? This sucks. So in the novel I’m driving at the idea that justice and freedom don’t wait. It’s not, well, you need to suffer just a little more and then things are going to be peachy in fifty years. No. That was the rationale for colonialism and you can see the wreckage that left behind. So yes, you’re totally right, it’s a novel about capitalism (amongst other things) and it questions this notion that our systems of governance and economics are somehow inviolable and handed down from Moses. They’re only ideas and policies. Ideas and policies can change.

One thing I want to caution against—and it’s something your line of questioning allows—is equating Fedor’s Jewishness with his approach to business. That’s verging on stereotyping Jews as having one monolithic idea about business. No such thing exists. That’s important. Fedor is a classic American businessman, concerned about the bottom line and his own legacy, etc. but there are other business people, Jewish and non-Jewish, who have different priorities from Fedor. So I don’t want people to ever think that Fedor represents Jewish business people. There are plenty of Jews and Muslims and Italians and Koreans and Peruvians and Protestants like Fedor. Tons. And tons who aren’t like him at all. I just want to make sure we aren’t saying Fedor represents Jewish businessmen. He doesn’t at all. And that would be dangerous for people to think.

Emperor is also about a deep, non-businessy correspondence between Chinese and Jewish cultures, both of which have traditions that go back several millennia. You present them to us in parallel—I’m thinking of the moment when Alex’s memory of breaking a family religious object leads into his participation in the Chinese ritual of “corpse walking.” And there’s another moment when Chairman Mao and Rabbi Hillel—one of the great Jewish spiritual authorities from two thousand years ago—are quoted as saying basically the same exact thing. Was this element there from the conception of the book, or did it arise during the writing process?

This came through during the research when I realized there were so many parallels between these two ancient cultures. I couldn’t believe how much they shared in terms of values, customs, humor, neurosis, etc. There are similar preoccupations with tradition, family, legacy, inheritance. So I think part of Alex and Ivy’s love story is discovering these connections. And they are also wrestling with which traditions to preserve and which to break. How many traditions can you lose before you lose your sense of self? Before you lose your identity? And what happens when some of those traditions/customs that define you are actually completely inhibiting or oppressive. Do you still cherish them because they made you? Because your grandmother did them? So Alex and Ivy are asking the same question: what to keep and what to lose?

But most of this I found out through researching and reading. At the heart of the book are two parallel utopian myths: for the Jews it’s The World to Come and for the Chinese it’s the Peach Blossom Spring. I say myths, but if you’re Jewish, you could believe the story is fact. So I don’t mean it disparagingly. I just mean that the psychology behind both stories is fascinating—this idea that there’s a better world we’re waiting for. We’re also talking about two cultures obsessed with the past. The past is alive. Always bleeding into the present. And finally, both the Chinese and the Jewish people have long traditions of labor activism, trauma, revolution, and literature.

And humor! Just to give you a quick example, my Chinese friend Vega and I were at his parents’ house outside Guangzhou, and after dinner we tried to go for a walk but his parents wouldn’t let us leave the house without umbrellas (even though it wasn’t raining). It could rain, they said. And one must always be prepared. We went to the front hall closet. They had a dozen umbrellas in a floor vase and they proceeded to take out each one and argue over the merits and demerits of every umbrella—this has a broken rib, don’t you remember, and this one’s going to tear any minute, and this one’s got no handle. They were all inadequate in some fundamental way. Vega and I kept saying they’re fine, but they weren’t fine! Oh, no. Not fine at all. And this went on for fifteen minutes until the parents finally agreed, after weighing all the pros and cons, that we should go walk umbrella-less and throw caution to the wind. Who knows what would happen but they and their umbrellas were powerless to stop it. I LOVED it.

I could’ve been listening to my grandparents back in Lynn. I listened to those conversations my whole life. Vega’s folks were arguing about a few fundamental things—can we protect our children, can we provide for our children, why do we feel like we’re blowing it in both regards, and then, slumped in grief, why are we ultimately powerless in this world? All because of umbrellas.

There’s an even further Jewish/Chinese “rhyme” in the book: the correspondence you draw between Jewish persecution in Europe—cresting in the 20th century but certainly not limited to it—and the brutal crackdowns of the Chinese government, from Mao’s “Long March” to Tiananmen Square. You describe both sets of citizens trying to survive such purges as escaping “goose stepping boots.” My question is the same as immediately above: was this in the recipe, or part of the cooking?

Definitely in the cooking. The more I read about the Cultural Revolution and other traumatic stages in Chinese history (there’s too many to list), the more I felt resonance with Jewish history. But here’s the kicker: so much of the literature written about the cultural revolution is funny. I mean, it’s tragi-comic. In the face of persecution and starvation and famine and ludicrous bureaucracy there’s still a joy and humor for life. But I didn’t know that until I spent six months reading everything I could about China. Those connections you’re noticing really emerged then and started to find their way into the plot. But more than chunks of plot, they’re just the basic yearning of Alex to know himself through Ivy. He wants to know Ivy, of course, but he yearns to know himself through knowing Ivy. Same with Ivy, but vice versa. They don’t know this consciously, but that’s the real plot of the book.

Let’s shift gears a bit and talk about the Jewish literary tradition in America. Saul Bellow. Bernard Malamud. Philip Roth. Norman Mailer. How do you dance with them? What do you borrow, what do you reject, and who do you argue with most?

Let’s shift gears a bit and talk about the Jewish literary tradition in America. Saul Bellow. Bernard Malamud. Philip Roth. Norman Mailer. How do you dance with them? What do you borrow, what do you reject, and who do you argue with most?

I learned so much from them in terms of how to write that most of what I’ve learned I’ve assimilated somewhere in the back of my head and I couldn’t begin to tell you in concrete detail what it is. The dialect of Jewish people is what I love most. When I close my eyes and think of those authors, I can hear the unique way that different kinds of Jewish people talk and it feels like home. They all write so differently though. I mean, so does Shalom Aleichem and Tillie Olsen and Grace Paley and Nicole Krauss. They’re all major influences but it’s so hard to pinpoint what I borrow or reject. I’m not them. That was the hardest part to accept. I want to be Grace Paley badly, but I’m not. It’s hard to accept that, right? She’s a genius. Roth’s a genius. So is Virginia Woolf, who’s not Jewish at all. These people are Gods to us. But you can’t be them. If you keep trying to copy them, you’ll never write a decent word. There’s a real danger in idolatry. I think that’s what Raiders of the Lost Ark was trying to teach us with the face-melting scene. You have to be yourself. And that’s the hardest part. Living with yourself. Especially when your personality is as exhausting as mine. I’m kidding, kind of. But I’ve tried to stop comparing myself. No, I’m actively trying not to compare myself. It’s a daily battle. I also love David Bezmozgis and Leonard Michaels. But who am I? That’s the yearning thing Robert Olen Butler talks about.

Speaking of Butler, we couldn’t get through this conversation without talking about his influence, since we’re both former students of his. What do you borrow from him and in what ways do you argue?

The concept of yearning is of course Bob’s aesthetic theory. And I agree with it. The jet fuel that propels a narrative forward is the protagonist’s yearning for self, for identity, for a place in the world. I think that’s true of Hamlet and Beloved and The Wire. So that’s something we really agree on. We don’t disagree on much aesthetically, but I spend a lot more time in my classes on technique and craft. He’s more focused on this concept of yearning. The other thing we agree on is that you have to write every day to get into the consciousness of the character. We also agree that literary art, done right, is really freaking hard to write.

I’d like to turn back to China to close out. Why are we as a culture fascinated with China and what can we learn from them? I don’t mean some kind of moral or economic lesson, but instead what we can learn about human nature from the contemporary Chinese experience.

Unfair! That’s too hard a question. I think my novel answers that question as best as I can. You can ask Chinese scholars and reporters who probably can give you a heady answer but I tried to dramatize the answer to your question in a novel. That’s the beauty of art, I think. It can’t be reduced. I’m not sure I can distill my novel into a pithy line or two and maybe that’s why I wrote it to begin with. It’s complex. I’ll say this: there’s an underlying universal human condition, something connecting us all, and that’s I think what we’re fascinated by. I think there’s something in my book about the universal human struggle for independence, dignity, free speech, and justice.