From my very first encounter with reading a Liz Breazeale story, I was hooked and eager to read more. Her prose style is lyrical, vivid, and engaging. She explores new terrains and forms in her fiction that speak to the tumultuous times in which we live.

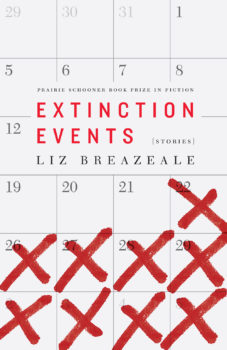

It was no surprise to learn that her debut collection of stories, Extinction Events, was named the winner of the 2018 Prairie Schooner Book Prize. This collection, published last fall by the University of Nebraska Press, was one of my best reads of the year and stuck with me long after I’d finished the final page. The stories in Extinction Events contain multiple layers beyond the impact of cataclysm and loss. Readers will encounter moments of darkness and longing, but also an intimacy with the characters that reveals love, vulnerability, and wonder. With an impressive range of narrative form and structure, these stories explore everything from the hazards of intimacy through a husband’s obsession with creating a definitive “Disaster Preparedness Handbook” to the loss of a sibling framed by a description of exhibits in “Devil’s Tooth Museum.” In the title story, “Extinction Events Proposed by My Father,” the complex father/daughter relationship is nestled within theories about the dinosaur’s demise, and through the lens of a Q&A in “Experiencers” a woman grapples with the suspicion of an alien abduction and the feeling of being alone and disconnected from those she loves.

Liz Breazeale earned her MFA in fiction from Bowling Green State University. Her work is forthcoming or has appeared in Hayden’s Ferry Review, The Collagist, Fugue, Pleiades, Salt Hill, Fence, The Sycamore Review, Passages North, Booth, Territory, and others.

Interview:

Jennifer Marie Donahue: I admired how the stories in Extinction Events push the definition of what a story can accomplish in terms of form and scope. What writers have influenced your development as an author?

Liz Breazeale: What fascinates me is when a writer takes an idea and uses something outside of the traditional story structure to implement that idea or to tell that story. Because I do think that the way that a piece looks on the page is so important. Physically, the white space, the blank space of a story, can tell so much. I read a lot, so I think that gives me more insight into what other authors are doing. For me, seeing other authors do bold experimental stuff, especially with form and structure, always blows my mind. I always go back to Carmen Maria Machado and her work in terms of structure. When I read “Especially Heinous” in Her Body and Other Parties, the story really stuck with me. That is, I think, the quintessential example of the form informing the piece and the piece informing the form in turn. There is no other way that piece could exist. Thinking about that exploded the way I thought about my own work and the way that I wanted to write. For me, there are so many things that we can do with language and with the form of the short story. Why not try all of it?

Has reaching in a more experimental direction been an evolution in your work?

Has reaching in a more experimental direction been an evolution in your work?

I always try to have my mind open. What can physically and visually be done with words on a page? I think it all comes down to experimentation. There are stories that I’ve tried to crunch into a non-traditional experimental format that just haven’t worked. I’m thinking specifically of “The Disaster Preparedness Guidebook” in my collection. It had a ton of different iterations. I wrote the very first draft when I was on vacation in Hawaii with my family. It started as dialogue between two people driving up the side of a volcano. It went through a bunch of formats. It wasn’t good. It was very bad. So, I think time is important in the writing process, taking time between drafts. I think it allows me to consider: What does this look like and what is the actual form of this? What does this story want to be?

Is the work of discovering what a story wants to be done in revision?

Revision is so important. I think revision is really, really hard work. Revising is scary because you are erasing something that you have already written or that already exists on the page. You are taking it out and saying, What I have done now, later, is better. I think I revise probably past the point of usefulness. I revise obsessively. One of the greatest joys in writing is when I’ve finally fixed major structural issues and dive in going sentence by sentence. Dealing with that is one of my favorite things to do. It gives me such joy. I’m excited by it.

You started Extinction Events as part of your MFA thesis. Is there one story that you can trace back to as the beginning? How did your vision transform over time while you worked on this collection?

I don’t remember a specific story, but I remember talking to one of my professors, Wendell Mayo, who recently passed. I remember what he said to me but I don’t remember what story it was in response to. He said: You are doing a lot with mothers and daughters, relationships, the death of relationships and extinction and I would love to see what a collection like that would be like. I think you really have something there.

That stuck with me. Someone saying: I see everything that you are doing and see everything you want to say and I think it matters. That was a huge thing.

Extinction Events taps into important issues of our time. I’ve read fiction that has tried to deal with contemporary issues and it can feel very heavy-handed. Rather than teaching a lesson, your stories feel like they open the reader’s eyes to the issues in a more organic way. Is that a hard balance to strike?

Whenever I write something I have a baseline assumption that no one is reading it. I’m shouting into the wind. Once I’ve assumed that, I try to speak to the most intelligent person I could ever imagine reading my work. I don’t ever want people to read my work and think: I feel condescended to. There are so many really important things happening right now. I wanted to speak to the ideal reader.

In the first story of the collection, “Un-Discovered Islands,” a woman remarks, “We won’t let ourselves be eroded. You can’t disappear us.” Many of the stories illustrate how women’s lives are influenced and shaped by imbalances that exist in their most intimate relationships. I want to know more about the link between these feminist themes and ideas of extinction and erosion.

“Un-discovered Islands” was one of the last stories I wrote. I constantly feel like women are being, for lack of a better word, eroded or erased. I’m constantly feeling like everything in society is built from the perspective of a straight, white man. So, women are constantly, constantly being degraded in some way. Our stories are being erased. Pretty much anything we say or do is wrong in some way. I think at a certain point I got really angry about that.

So your anger helped fuel this thematic focus?

Yes, in some ways.

I read some stories that appear in Extinction Events when they were first published in literary journals. Yet, when I read those same stories as part of the larger collection, I experienced them differently. These stories are connected to and in conversation with each other and they “bump” into one another in a way that highlights specific themes, provides contrasts, and adds depth to the narrative. Can you talk about how you worked out the order of the stories and created this broader narrative arc and conversation? It is impressive to read a story once and then read it again in conversation with other stories and find something new. So, tell me your secrets.

Structuring a story collection is so hard. Basically impossible. How do you put these things in any kind of order? By the time I got to the point where I was ready to send the collection out, I really could not grasp the larger picture. So, I sent it to a good friend: Here’s what I think should be the first story and the last story. You’ve read every story in the collection. What do these things mean? What do you think? This is a clown car of disaster. What is happening? I always wanted “Un-discovered Islands” to be the first story. It is a really good eye into what I am working with and I felt like it was the strongest story in the collection. My friend gave me the idea to put “Experiencers” last and her thoughts on the order for the collection and her reasoning which was super helpful. I think having someone else read your collection is a great idea.

Structuring a story collection is so hard. Basically impossible. How do you put these things in any kind of order? By the time I got to the point where I was ready to send the collection out, I really could not grasp the larger picture. So, I sent it to a good friend: Here’s what I think should be the first story and the last story. You’ve read every story in the collection. What do these things mean? What do you think? This is a clown car of disaster. What is happening? I always wanted “Un-discovered Islands” to be the first story. It is a really good eye into what I am working with and I felt like it was the strongest story in the collection. My friend gave me the idea to put “Experiencers” last and her thoughts on the order for the collection and her reasoning which was super helpful. I think having someone else read your collection is a great idea.

If you could go back in time and give yourself a piece of advice while working on this collection of stories, what would it be?

There are so many things. Can I just give myself, labyrinth style, a way to go? If I could give my past self a piece of advice, it would be: you are strange and that is a wonderful thing. Trust your strangeness. Live in it.

I love that. How do you keep your artistic side alive and happy and hopeful?

By following what I’m interested in. If that is a strange thing like reading a book about the color red, and what the color red has looked like in the past two centuries, then sure. Go for it.

Trust that it will be something useful on the writing end?

Yes, go for it. I think it is seeing what you love and being okay with that. Seeing what interests you. Everything for me could spark a story idea. Seeing what you are interested in and trust that could lead to something or mean something. Following that.

What are you following right now? You’ve recently published new stories and have some forthcoming in 2020. Are you working on another collection? I would love to hear more about your new work and current obsessions.

So, right now I’m obsessed with feminist body horror. I’m really fascinated by the ways in which we talk about the female body, and what we say, and also just where all of that comes from.

That feels like a natural extension of ideas you explored in Extinction Events.

I think especially today there is so much. The people who are writing the laws about our bodies—“our” meaning people who identify as women or femmes—the people who are writing laws about our bodies genuinely do not understand the processes involved in having this body. It is really infuriating. Whenever I get really angry, my process is to write.

I admire that you’re able to channel that anger into something productive. I can’t wait to read your new work.