Editor’s Note: As we approach our tenth year of publishing Fiction Writers Review, we’ve decided to curate a series of “From the Archives” posts that we’ll re-publish each week or so during 2017. Some of these features are editor favorites, some tie in with a new book out from an author whose worked we’ve covered in the past, and some are first conversations with debut authors who are now household names.

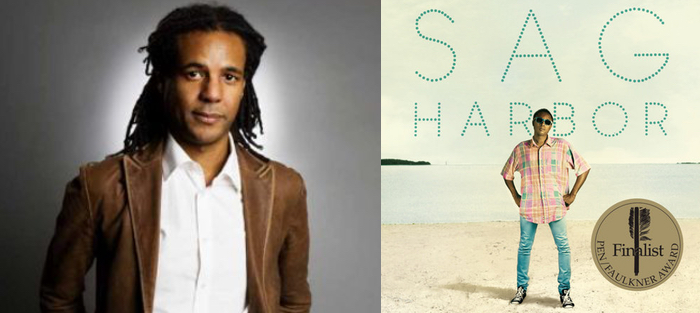

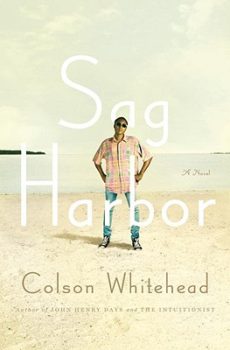

This week we’ve returned to Jeremiah Chamberlin’s interview with Colson Whitehead, which was originally published on May 30 of 2009. He spoke with Chamberlin on May 16th, during his visit to the 2009 Ann Arbor Book Festival. His then-most-recent novel, Sag Harbor, had just been released. Whitehead’s new novel, The Underground Railroad, won the National Book Award last fall.

Interview:

Jeremiah Chamberlin: Some authors describe the writing process as a kind of possession—they hear the first line, or a character’s voice, and it leads them into the story. Others think of it more like exploration. Was there a voice or an image or an artifact that brought you into Sag Harbor?

Colson Whitehead: I lost all my vinyl in a basement flood a couple years ago, so I had to go back and get all this old stuff (hip hop and the new wave and post-punk). And each time I remembered some old artist, I remembered more and more of the 80s. So for me, I was consciously looking out for artifacts of the time—new Coke, old Coke, certain songs, certain TV shows—trying to find what would work for Benji’s story and what wouldn’t work.

So there was already a story percolating as you accumulated these artifacts?

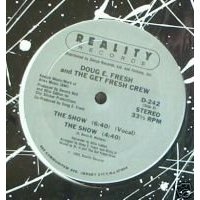

I knew it was going to be the summer, and early on I decided on the summer of 1985. I wanted to write about Slick Rick and Doug E. Fresh and “La Di Da Di” and “The Show,” this very monumental single that came out in the history of hip hop. It spoke to a time when hip hop was changing from a very juvenile form into a more mature one. So you had these corny singles and bands like U.T.F.O. (Untoucable Force Organization) and Whodini, and then eventually N.W.A. and gangster rap in the late 1980s.

I knew it was going to be the summer, and early on I decided on the summer of 1985. I wanted to write about Slick Rick and Doug E. Fresh and “La Di Da Di” and “The Show,” this very monumental single that came out in the history of hip hop. It spoke to a time when hip hop was changing from a very juvenile form into a more mature one. So you had these corny singles and bands like U.T.F.O. (Untoucable Force Organization) and Whodini, and then eventually N.W.A. and gangster rap in the late 1980s.

I had also reconnected with Sag Harbor after fifteen years. I started going out there again, and each time I would bring friends out for the weekend I had to explain who this person was or whose house was that or what happened on this street. I was tied to the place in so many different ways, and there was a history of this black community that had to be told. So it was good material, and it was material that I knew very well. But I couldn’t get to it. I had to finish Apex.

Then my daughter was born and two years passed before I was finally able to start working on it full time. But very quickly I knew that I wasn’t going to have artificial coming-of-age events like a lynching or a big fire or someone accidentally killed. So I did spend a lot of the time when I wasn’t writing thinking about how to elevate these very mundane moments into the stuff that was art worthy. I started making notes like, Go to the beach? Get a summer job? And then I had to ask myself, “How do these small events eventually become chapters, become compelling points of intrigue for the reader?”

In her essay “That Crafty Feeling,” Zadie Smith once said she felt there were two types of novelists: The Macro Planner and The Micro Manager. She said, “You will recognize a Macro Planner from his post-its, from those Moleskins he insists on buying. A Macro Planner takes notes, organizes material, configures a plot and creates a structure—all before he writes the title page.” Whereas Micro Managers, like herself, “start at the first sentence of a novel and…finish at the last.” In fact, it apparently took her nearly two years to write the first twenty pages of On Beauty because she was trying to establish the right voice and point of view to begin the book. But then, once she had that in place, she said she was able to complete the rest of the novel in five months. Your process sounds more like the former.

I always outline and have a pretty solid idea of beginning, middle, and end, though this can change over time. In my previous books, if I got sick of a character I could jump to a different section and work on that. So for the first time I didn’t skip around. But, again, I had a few years of not very dedicated taking notes where I could write two lines about, say, “Should I name the character NP?” Then that would be it for one month. Basically it was an ebb and flow of working on the book and taking notes.

But you had a vision of the broad architecture.

Yeah. Both things come at once—the voice of the narrator and how the characters talk, and also the larger structure. To jump off your Zadie Smith example, I am sort of casting about for the first fifty or seventy pages as I finally nail down the voice. At that point I might go back and smooth out the early parts that aren’t in that voice. The first hard part to get through is finding the voice, and then also setting the stage. I always find introducing the characters—are they tall, short, blah, blah; Sag Harbor’s a town that was founded in blah, blah—irritating. So I really like it when I can let it rip. In this book, the first two chapters are setting the stage, introducing the players. But I had a lot more fun writing once I could let Benji have free reign.

What I liked most about the narrative voice is your blend of the adult retrospective and the vernacular of this period, which helps capture the personality of Benji as a boy. Was that something that you had to work on?

Before I started writing, I knew that it had to be an adult looking back on his childhood because I would get bored out of my skull if I had to have a fifteen-year-old’s voice for three hundred pages. I know people fudge it by having very precocious narrators who are wise beyond their years, but that feels like a real cheat. I was not a very articulate fifteen-year-old, so why pretend that fifteen-year-olds are incredibly articulate and wise about their world? My narrators generally have a certain kind of critical faculty. They’re analyzing what the characters are doing in larger social structures. So I wanted to have an adult voice looking back upon teenage years with that kind of critical distance. You know, being able to break down their cursing grammar.

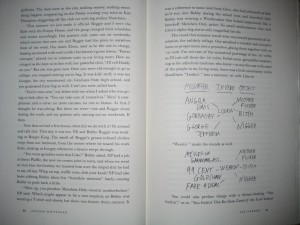

Yeah, I love the graph in the book.

What I like about writing is the super zoom in, and getting close on some sort of mundane thing, like frozen food or Classic Coke. My idea of a fifteen-year-old couldn’t have that kind of critical voice in the same way.

You mentioned the historical side of this black community in Sag Harbor earlier. Did you ever consider tackling this subject as nonfiction?

No. [Laughter] I’m not sure, outside of two pages, what the story is in a journalistic sense. I mean, they came in the thirties, started hanging out there, and…that’s the story. Perhaps there is an interesting story about my grandparents’ generation and their ideas of the world and what it means to be American and a black American and what it meant to achieve, to be part of this new emergent black middle class, and to have this place. However, I wouldn’t want to spend two years talking to the old timers. [Laughter.] Someone else can do that.

I was just curious because so much of the book has this interesting idea about legacy and what we inherit.

Yes.

Benji seems very interested in what he should know versus what he does know, and that’s involved with the theme of identity creation woven throughout the book. The thing that I also found interesting, though, which we see during the picnic when he’s watching the footrace and observing both the kids and adults around him, is that while part of identity creation is a very active process, another part of it seems totally out of one’s hands. That there are “roles” we fit into.

Well, nature or nurture, right? There are cultural codes, teenage codes, and social cues you pick up and learn to be a functional member of society, not ostracized and humiliated constantly. And that’s the conflict between our idea of self and the way people are accepted into the larger community. Then there’s this idea that we are all pretty much alike—the kid with the scabby knees and the messed up haircut is us at some point, and the older, middle-aged guy holding his Budweiser on his paunch is us in the future, and then we’re going to be this oldster looking down upon our previous selves with a certain kind of bemusement, a kind of acceptance of the time traveler’s paradox. Because you can’t actually go back and fix your past, you can’t go give your earlier self advice and have it move through things. You have to experience it yourself. In that way we’re not individuals. We are part of this essential human being who is always learning and is always being replaced by some better version or older version—hopefully a more mature version—that is taking the place of who we are now.

It’s saying goodbye. But I think particularly with Benji there’s this hope that one day he will be on the sidelines of the race with his wife and his kid. That he will find himself. He’s campaigning to become Ben, and not necessarily getting results, but at some point this campaign will have some sort of victory or success.

The book also has so much to do with figuring out what nostalgia is, and how much of that’s a manufactured process.

Embracing the myth and realizing the myth is just that: a myth.

And then embrace it again.

Yeah, exactly. But it’s okay. Or forgetting. This constant forgetting that it is actually fake, and discovering that it’s sort of false and then forgetting again, and getting caught up. This cycle of remembering and forgetting that it’s fake.

Yeah, it’s okay. [Laughter.]

Speaking of adults and childhood, let’s talk about the parents in this book. In Toure’s Times review of Sag Harbor, the book is briefly described as a Peanuts world, absent of adults. Yet Benji’s parents—to borrow a metaphor from the book—seem like the “undertow” of this novel. Would you talk about their role here?

There’s no strong plotline in the book, so how do you create tension, anticipation? Part of that is by withholding information and revealing it at a key time. So, a hundred pages go by and you’re like, “Where are the parents? What’s going on? What’s the back-story of their disappearance? Why aren’t they there?” It’s explained in a simple way: they work in the city. But how does that play out over the weeks? From chapter to chapter I’m establishing and then gradually building tension around this greater darkness that is slowly revealing itself. So they [the parents] appear, disappear. The book is ordered so that moving forward, creating tension, dissipating tension, there’s more humorous parts held up against more miserable parts. For example, what is the effect when you go from the barbecue from hell chapter to this junior spy caper about getting into a club?

And what is that, for you?

It’s an attempt to get to how we live. We’re all veering from the tragic and the blessed moments across the span of a day. The Colossus of New York is very preoccupied with that, going through people’s heads from sentence to sentence. Some people are having a good day and some people are having a bad day, and it can change over the course of a city block. You can be having a good day on 62nd Street and by the time you get to 63rd something horrible has happened. Whether it’s Beckett or Richard Pryor, artists who I liked growing up veer between the capricious horribleness of the everyday and the absurd beauty of existence. So for me the duality has always been important in terms of how I see the world, and I think that plays out in my fiction.

It also goes back to the idea of grief and hope bumping up against each other, right?

It’s simultaneous, yeah.

We’ve talked a lot about how this book came into being and was constructed, but I’d also be curious to know about some of the most joyful moments you had during the writing of this book.

[Laughter.]

It’s a cheesy word, isn’t it?

No, no, it’s true. That’s how I feel about it. When I think about the writing of the book, I have a very strong sense of where and what room I was in. Was I in Sag Harbor? Was I in Brooklyn? Was I on book tour? Was I on the train? I remember when I came up with different things, so my reaction to the book becomes very sentimental. Like, “Oh, that was a rainy day and I was really hungry, and I broke open my notebook and I had a productive afternoon, and that was a good day.”

I remember the week of the last chapter. I’d already written the first seven chapters, so the voice was down. I knew what I had to do. I knew the characters well, I knew what I wanted to say, and I’d been thinking about it on and off for four years, so that chapter came very effortlessly. I was sad to be done, but there was something really nice about finally pulling all the threads together that I’d been working on.

You’ve talked pretty openly about the fact that a large part of this book is autobiographical. What, then, was the greater project of the novel?

With earlier novels, there were questions I wanted to explore from the outset. “How do you update this industrial age from John Henry to the information age?” Or, in Apex, “What do names mean? What does it mean for a city to evolve over time? And how do we ascribe meaning to places with the faulty tool of language, which is already a mediated meaning?” So with this one, I didn’t have a set idea. I just wanted to describe a way of being in the world that hopefully overlapped with other people’s ways of being in the world.

Do you think that changed your process in writing this book compared to the others?

When the writing slowed down it was because I was trying to figure out what I remembered from being a teenager, or what I had discovered about the time period and the community that would work in the story. In previous books I had a lot more free reign to invent stuff. Some of them take place in very fantastic stages or there’s a kind of heightened reality. So I had to figure out how to play it straight and stick to the facts and make the facts useful in the story.

There seems to be ways that the language shifts between your books, too. The prose of John Henry Days, for example, is chiseled in a very different way than the prose in Sag Harbor. Do you think that has more to do with your language evolving as a writer in general, or rather the narrative differences in those novels?

The narrative differences, yes, but also just maturing as a writer. Ben has a sort of voice, and I have to stick to that. With John Henry Days I wanted the narrator to bend to whatever situation or character he was narrating. So the J. Sutter chapters are very frenetic, very charged up. With the John Henry chapters, on the other hand, I wanted a different kind of prose—shorter sentences, fewer adjectives, shorter nouns. It’s very direct. I was trying to use the right tool for the job. So it is both. Hopefully ten years later I’m just a better writer. If I did John Henry Days now it would look different, because I’m interested in different things and write differently.

A final question as we wrap up. Is there one thing that you’ve been happy to let go of in this process?

This may change, but I feel comfortable with where I am in my career and in my home life. I’m not sure what I’m going to do next, but whatever it is, it’s okay. I enjoy this book, which I’m very proud of, and I enjoy having done some good work. When the next thing presents itself, I’ll get myself into it. But instead of beating myself up and getting on this treadmill and saying, “I have to prove to myself I can do this,” or that I have to do a big book or a small book, I feel my books have been different enough that I can chill for now. This month, anyway. [Laughter.]

For the next thirty days, right?

At least until June.