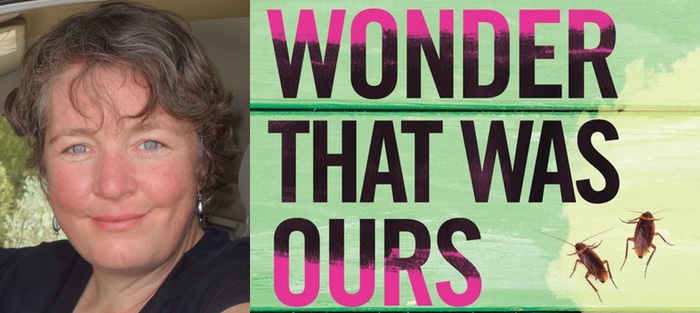

I met Alice Hatcher about five years ago via a Tucson book club for writers. When I first read an earlier draft of Alice’s novel, I was immediately blown away by the voice, humor, intellect, and heart of Alice’s writing, not to mention her audacity. A novel narrated by cockroaches?! Alice quickly became a good friend and a trusted reader. We’re both now semi-regular attendees of Write Wednesday, a weekly meetup of Tucson writers who get together to write, to commiserate, and to celebrate each other’s successes.

Alice’s novel The Wonder That Was Ours won the 2017 Dzanc Book Prize for Fiction. Her work has appeared in Alaska Quarterly Review, the Beloit Fiction Journal, Fourth Genre, Notre Dame Review, and many other venues.

Interview:

Michelle Ross: Writing a novel in the collective voice of cockroaches is an unusual and risky choice. Chrissy Kolaya, one of the judges of the Dzanc Novel Prize, said she was highly skeptical at first. But quickly the cockroaches, and your writing, won her over. In a short essay titled “The Metamorphosis of Graham Greene,” you talk about how you came to this unique narrative choice. A Graham Greene story led you to experiment writing this novel from an opinionated and omniscient, but not yet defined, point of view. When readers demanded to know who this omniscient and opinionated narrator was, you landed upon the cockroaches infesting the main character’s cab. Although a strange and unexpected narrative choice, as you point out, the cockroaches are in a way a natural choice as an omniscient narrator. You write:

Graced with hyper-sensitive antennae attuned to the subtlest gestures of humans armed with the insecticide Roach Out! and rolled-up newspapers, they would know my characters’ very thoughts and feelings; their survival would depend on it. With access to air ducts, sewers and drain pipes, the roaches could witness anything taking place anywhere on my fictional island.

I wonder, even as you realized how well cockroaches could work as an omniscient narrator, were you at all hesitant to attempt to inhabit their voice? Or did you fully embrace the choice from the start?

Alice Hatcher: I was scared out of my mind when I started narrating my novel with a collective of cockroaches. At first, I limited the roaches’ commentary to short interludes, Greek choruses, or Roach choruses, between chapters. I kept the rest of the novel in third-person. Then an interested agent remarked on a tonal inconsistency in the manuscript, and with dread, I realized he had identified a real problem. I say dread because I knew I needed to overhaul the novel yet again. I could either delete the roach choruses and rethink the third-person sections of the novel, or I could rewrite the entire novel from the roaches’ perspective. I knew that cockroach narrators could provide a wide-angle lens on human foibles, as well as commentary on human behavior that made sense, given their perspective.

Still, I worried I was shooting myself in the foot. Most people are squeamish about cockroaches, to put it mildly. I made my final leap of faith while watching a Green Bay Packers game on TV, after Aaron Rodgers threw one his famous Hail Mary passes. I remember sitting on the couch, staring at replays and thinking, “Why the hell not?” After years of searching for a narrator, I realized it was time for a risky play. I actually imagined the roaches dancing in the end zone. Once committed, I decided that I was going to publish the novel with cockroach narrators or not at all. To do anything else would have been a betrayal of a certain vision.

The voice of the cockroaches is so funny and charming. Did their collective voice come easily? Or was there much trial and error?

The voice of the cockroaches is so funny and charming. Did their collective voice come easily? Or was there much trial and error?

Once I started the draft called “Roach Rampage,” writing became almost easy for the first time in years. That’s how I knew I had found the right narrator, and that the cockroaches were serving the story by allowing me to explore questions close to my heart—questions about alienation and compassion. I always identified with all of my characters in some way or another. Writing Wynston Cleave, I drew upon my experiences as a professor teaching social theory to students who had never questioned the workings of capitalism. Tremor emerged from certain childhood experiences, and from my adult experience working at a hotel where guests routinely demeaned the staff.

All the primary characters are projections of my personality, but the roaches most embody who I am. I’ve always been an outsider. I was a “tomboy” in a grade school straight out of Pink Floyd’s The Wall. It was a Catholic school, and the teachers let us police ourselves on the playground in the interest of character-building. I was a bit of a freak in high school and the youngest member of a highly dysfunctional family overseen by a volatile patriarch. I routinely had the crap kicked out of me. I spent my childhood and adolescence moving under the radar as much as possible. I developed a healthy suspicion of authority and hyper-sensitized antennae. When I left home, I couldn’t look back. It was too painful. So, I felt entirely comfortable inhabiting the mindset of displaced cockroaches on the run from rolled-up newspapers and Roach Out!

What other writers inspired this novel or did you find yourself turning to when in need of some guidance?

I found myself turning again and again to James Baldwin’s novel Another Country. Baldwin’s intellect was staggering, as anyone knows if they’ve read his work or watched his 1965 debate with William F. Buckley. I encourage everyone to google that debate. I embraced Baldwin as an inspiration—however intimidating—because he was so adept at inhabiting the worlds and exploring the views of people who weren’t, on the surface, like him. He wrote about straight and gay characters, men and women, black and white people, privileged people and people just getting by. While writing about the vast gulfs that divide Americans, he never lost sight of our shared humanity.

I also held fast to Gould’s Book of Fish by Richard Flanagan, a truly bizarre and wonderful novel about a man morphing into a fish in a Tasmanian penal colony. That’s a terrible summation of a brilliant book that served as a security blanket at times. Whenever I feared I was on the wrong track, I reminded myself that my favorite authors have done much weirder things to greater end.

You have a PhD in History. Did you always write creatively? Or did you always know you wanted to write creatively? Or is that something that came later?

I grew up wanting to write a novel, but I was too afraid to make a serious attempt until I was in my late 30s. I did start a novel after college, but I lacked the maturity to produce anything worth publishing and abandoned ship. The novel resembled a badly written memoir. I wrote as if I were the only person who had ever fallen in love, had sex, drank too much, etc. I felt like a failure and ended up retreating into the ivory tower in some half-baked attempt to prove to myself and anyone who might notice that I wasn’t an idiot. I made the mistake of chasing a degree for validation. It might have been for the best in the end. I was off the rails in my 20s, and grad school gave me the structure and stability I desperately needed. It was boot camp for me, and I happened to be in boot camp with some of the smartest people I’d ever met. The downside is that I ended up distracting myself from my real passion. The upside is that I gained the self-discipline and intellectual tools I needed to develop as a writer. I had the luxury of reading more in a few years than most people read in a lifetime, and much of what I read shaped the novel.

One of the agents to whom you pitched this novel and who then read the book said he admired the writing, but he ultimately passed on representing it because he said he didn’t think he could sell a novel set in the Caribbean, that this locale wasn’t in fashion. Other than that being a weird and depressing statement about the way the literary publishing world works, it also makes me curious about what drew you to this locale and these characters in the first place. How did your background as a historian lead you to this novel or influence the writing?

The earliest inspiration for the novel was a story told by a friend who had worked on a cruise ship with routes in the Caribbean. One the most depressing parts of her job involved ejecting disruptive passengers at the next port of call. The people she kicked off were usually belligerent drunks, employees who’d had sex with vacationing passengers, or passengers who had committed an assault. Sometimes they were failed suicides. It was all about liability. I couldn’t stop thinking about the cruelty of abandoning a severely depressed person in a foreign country, and about what that person might experience.

Then I started imagining two people kicked off a ship at the same time and wondering how they might relate to each other. It’s easy to assume that shared trauma creates close bonds between people, but shared trauma can push people apart, especially when they see each other as painful reminders of something they’d rather forget. My novel started off as an attempt to explore the alienation experienced by two people with little except a painful experience in common. There’s a reason the cockroaches refer to Sartre’s play No Exit. Of course, the roaches can’t stand the play. It reminds them of everything that’s wrong with humans.

So much came from my experiences researching and teaching the history of British imperialism and the Atlantic slave trade. Given my training as a historian, it was almost inevitable that a novel that began as a story about two hapless Americans kicked off a cruise ship took on much larger dimensions. The interpersonal relationships between individual characters were inseparable, in my mind, from the social and racial dynamics on the island. The more I wrote, the more certain secondary characters began to pop, to become primary. It all made sense. I never wanted St. Anne, the novel’s fictional setting, to be nothing more than a backdrop for the misadventures of white tourists. We’ve all read novels that present a place or entire culture or group of people as so much wallpaper. The thought of writing a novel so grotesquely lopsided sickened me. Such a novel wouldn’t have represented the diversity in the world or captured the way social forces and complicated histories inform human interactions. By the time I finished the novel, the American characters had been eclipsed by the characters from St. Anne—Wynston Cleave and Tremor—mainly because Tremor and Professor Cleave have more complex relationships to the novel’s setting.

Several agents you queried also said that your novel was just too weird for the mainstream literary market. Obviously, that’s not the case for indie presses, which many people would agree generally publish more innovative and so-called weird fiction than the larger, mainstream publishing houses. Would you talk a little bit about your experience trying to find a publisher? How long did it take to find a home for the novel? What other hurdles did you encounter?

About one hundred agents rejected me. Dozens wrote personalized notes to tell me that they admired my writing (some were even effusive), but that the novel was “too weird” to have a “market niche.” My writer friends told me to take heart because I was getting positive feedback instead of form letters. They had a point. At the same time, I couldn’t help feeling demoralized and perplexed, given the abundant evidence that weird sells. George Saunders’ brilliant novel Lincoln in the Bardo comes most immediately to mind.

I get that many agents need to pay rent, and that they need to exercise caution in choosing what to represent—to the point that every agent seemed to be looking for the next Gone Girl when I was querying. It was just hard to maintain a sense of humor at times, though I did laugh when one agent wrote, “I don’t understand how cockroaches could be telling this story??? They can’t write!” I came very close to writing back to ask if I should have given my fictional roaches opposable digits and tiny pens, or opened the novel with a long essay about oral traditions.

Less humorous—because I paid serious cash for it—was my experience at a “Pitch Slam” organized on the “speed-dating” model. I was standing in a long line in a hotel conference room, sweating it out while waiting to deliver a 90-second pitch to a well-known agent. I could hear the agent’s conversation with a guy who’d just pitched a spy thriller set in Jamaica. The agent and author got talking about their favorite all-inclusive resorts, and all I could think was “I’m so fucked.” My novel presents a somewhat dim view of all-inclusive resort culture. That didn’t matter in the end. Ten seconds into my pitch, the agent placed her hands over her ears and said, “I find cockroaches disgusting. I can’t listen to this.” She shuddered and waved me away. Those were the times I felt truly hopeless.

To be clear, I had some wonderful experiences with agents. In fact, I can thank an agent for directing me to indie presses. Only two days after that pitch slam, a different agent sent me a very kindly worded rejection. She told me that my writing was “beautiful,” but that she feared she couldn’t convince the marketing teams at any publishing house to get behind the novel. She then suggested I look into indie presses and named a few she thought might be appropriate. At the time, Dzanc Books was running its annual Prize for Fiction contest. Submitting to Dzanc was was the best thing I’ve ever done. As I talk about this, I realize I need to send that agent a thank-you note. She was very generous with her time and knowledge.

Tell us about the phone call from Dzanc’s editor-in-chief Michelle Dotter telling you that you’d won.

By that point, I had resigned myself to the possibility that my first novel might never find a home. I had brushed the chip off my shoulder, learned from hard experience, and started my next novel. I felt pretty bruised, but I was more resolved than ever to keep writing. So, the call came when I was ready—when I had just determined not to let the market dictate my self-worth. As for the call, itself, I must have been pretty incoherent. I do remember Michelle Dotter saying, “Your life is about to get very busy.” She wasn’t kidding. I hear stories about how long it takes for novels to move through the production pipeline at big publishing houses. At Dzanc, we had a few months to prepare my novel for press, and it was all hands on deck. I’m glad. It’s easy to get obsessive to the point of panic in the final stages of editing, and I was happy to work intensely for a short period of time. I’m all about yanking the Band-Aid.

Would you be willing to talk a little about what this whole first book experience has been like? Has winning Dzanc’s Fiction Prize and now being on the long list for the Center of Fiction First Novel Prize changed your writing in any way?

I was blown away when I heard I had made the Center for Fiction’s long list. There are so many talented writers on that list, and I’m honored and humbled by the recognition. It’s too early to tell how this year has changed my writing. I’m not sure getting published has changed me as a writer, though working with Michelle Dotter certainly did. I had never worked closely with an editor before, and it was the first time I saw my own writing through someone else’s eyes. It made me self-conscious, but hopefully a better writer as well.

If you could offer one piece of advice to writers embarking on writing their first novel, what would it be?

It’s easy to be seduced by the image, maybe the myth, of the Kerouac-like author sitting at a typewriter, beside a pot of coffee and an overflowing ashtray, pounding out a novel in a few weeks. This myth of the unflagging artist cranking out thousands of pages at a time can be really damaging. The solitude and stress of writing a novel over several years can wear on a person, and it’s easy to beat yourself up for not getting things done as quickly as you’d hoped.

The reality is that life gets in the way. Illness and death don’t recognize your deadlines. Family members make demands. Friends need help. I thought it might take two years to finish a novel. It took me seven. By the end I was saying “hell or high water,” and it ended up being both. I’m proud I took time to get it right rather than simply get it done. My advice to aspiring novelists would be: prepare for a long haul. If you take pride in your work, you’ll be writing several drafts, if not several dozen. Ignore the skeptics who keep asking, “When is that damn thing going to be finished, anyway?” If you’re spending every moment of your free time watching reruns of The Bachelor, you might want to get a little more serious about your work. But if you’re putting in the hours researching, outlining or drafting, and things are simply taking longer than anticipated, be patient with yourself. As my father-in-law used to tell his sons, “Don’t shit on yourself. Other people will do that for you.”