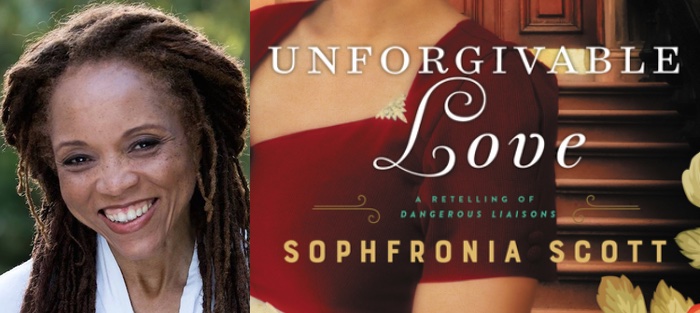

My first, clear memory of Sophfronia Scott was during a graduate school residency at Vermont College of Fine Arts in Montpelier, the summer of 2012. Sophfronia was batting during the annual poetry vs. prose softball game, and I was sitting in the shade (naturally), marveling at her arms with another classmate—how muscular her biceps were, and how fit she looked. A weird memory, I admit, but I didn’t know her very well at that time and my first impression was that she seemed a little intimidating. Fast forward five years, and I’ve gotten to know Sophfronia as a classmate, colleague, and friend, but somehow, that first impression of Sophfronia’s arms still symbolize what I’ve come to think of Sophfronia herself: strong, disciplined, and hard-working, but with one correction. She’s not at all intimidating. She’s quite the opposite. Warm, welcoming, and, something unexpected I learned during our interview, a romantic at heart.

Since we reside in different time zones, we chatted for this interview in the most modern way possible: through a combination of Facebook Messenger and email. She managed to answer my questions amidst a busy book tour for her second novel, Unforgivable Love (William Morrow), a vivid reimagining of the French classic Les Liaisons Dangereuses set in 1947 Harlem during the height of the jazz era. Unforgivable Love was an October People Magazine pick, and Kirkus called it “a dazzlingly dark and engaging tale full of heartbreak, treachery, and surprise.” She’s scheduled to release a staggering three books in five months, and she’s also the author of the novel All I Need to Get By (St. Martin’s, 2004), numerous short stories, essays, and articles, and spent the early years of her career as a writer and editor for Time and People Magazine. She holds a BA in English (not science . . . more on that later) from Harvard and an MFA in writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts. She lives and works in Sandy Hook, Connecticut with her husband and son (yes, that Sandy Hook . . . more on that later, too), and she’s a faculty member of Regis University’s Mile-High MFA in Denver, Colorado and the Fairfield County Writer’s Studio in Westport, Connecticut.

Did I mention she’s hard-working?

Interview:

Kali VanBaale: What I know of your background is too interesting not to discuss, so I want to start at the beginning. You grew up in Lorain, Ohio, the daughter of a Mississippi-born steelworker who never learned how to read, and a stay-at-home mother who instilled in you a love of books. How do you think your childhood experiences influenced your path to a life of writing?

Sophfronia Scott: Daddy didn’t know how to read, but I believe I’m a writer because of him. He was a storyteller. That’s how he seemed to communicate best, he was always telling stories and I noticed how people listened to him. He told stories about work, about women, about growing up in the south. Some of those stories influenced my novel Unforgivable Love. His voice is in my DNA so that’s not surprising.

Because of my childhood, though, I didn’t know anything about writing as a vocation. It was just something I did. It wasn’t until I was in college struggling with a science major I wasn’t happy with when a writing mentor said to me, “What are you doing? Don’t you know you’re good enough to get paid for your writing?” He helped get me on the path to a writing life and I’m forever grateful.

Now I must ask. What was your science major?

I was a biology major. And what did I learn? That the subjects of organic chemistry and neurobiology were not meant to be absorbed by my brain cells!

Ha! No judgment from a woman who needs a phone app to figure the tip. Back to your childhood, do you remember the first book you fell in love with?

Ha! No judgment from a woman who needs a phone app to figure the tip. Back to your childhood, do you remember the first book you fell in love with?

My fourth-grade teacher, Mrs. Gerken, gave me a copy of By the Highway Home by Mary Stoltz. When I think about it now, it’s an unusual book to give to a nine-year-old. It’s a story of a family in turmoil and grieving the loss of a son in the Vietnam War. The book blew my mind open because I was stunned that I could “see” every person and every setting even though there were no pictures on the pages! I always had stories running in my head and maybe this book helped me to see how big narratives and big images can be rendered on paper. I loved it and only wanted to read novels after that.

When do you remember first dreaming of being a writer?

I didn’t have that dream early on because I didn’t have a concept of what it meant or how one became a writer. I just wrote. I knew about Toni Morrison from my hometown of Lorain, but I didn’t know how she came to write books. When I went to college I noticed the students who participated in publications like the newspaper, Harvard Crimson, or the literary journal, The Harvard Advocate, seemed to have a professional level of focus and direction that I felt I didn’t have and didn’t know how to attain. I thought this even after I won a contest and had an essay published in the Advocate.

You started out as a writer and editor for Time and People magazines. How and when did you transition to creative writing? Or were you also writing fiction all along?

I wrote a few short stories right after college but then I was consumed by my magazine job. I was still learning about writing and I was in a great place for that, working with the best writers and editors in the business. But it wasn’t until I moved over to People that I started thinking about what I wanted to write on my own. Around that time, I made friends with a group of actors and being around such creative people made me think about writing fiction again. I even wrote a monologue for one of my friends and it was well received when she performed it. I started working on my first novel soon after that.

I mentioned earlier that in the span of five months, you’re scheduled to release a staggering three books—the novel, a collection of essays, Love’s Long Line (Mad Creek Books), and a memoir, This Child of Faith (Paraclete Press), co-written with your son, who was a third grader at Sandy Hook Elementary on December 14, 2012, and your family’s spiritual journey in the aftermath of that tragedy. How did you manage the creative transitions while working simultaneously between genres?

I’m a project-oriented writer—I think this comes from my journalism days. This means I don’t come to the desk with a goal of writing 1,000 words a day or anything like that. I’m thinking: “I have to work on this essay today” or “Today is all about finishing Chapter 18.” Because of this my creative transitions come naturally. Once my literary agent began submitting Unforgivable Love I went back to work on the essay collection I had started while in graduate school. Once that was done and submitted I wrote the book proposal for This Child of Faith. The hard part was when all the projects came to fruition at once. There’s no way I could have expected that. The essay collection and the memoir were submitted months apart, but they were accepted at the same time. So, I had to write the memoir while working on edits for the novel, which had sold earlier, in May.

I’m a project-oriented writer—I think this comes from my journalism days. This means I don’t come to the desk with a goal of writing 1,000 words a day or anything like that. I’m thinking: “I have to work on this essay today” or “Today is all about finishing Chapter 18.” Because of this my creative transitions come naturally. Once my literary agent began submitting Unforgivable Love I went back to work on the essay collection I had started while in graduate school. Once that was done and submitted I wrote the book proposal for This Child of Faith. The hard part was when all the projects came to fruition at once. There’s no way I could have expected that. The essay collection and the memoir were submitted months apart, but they were accepted at the same time. So, I had to write the memoir while working on edits for the novel, which had sold earlier, in May.

What challenges did you encounter in writing across multiple disciplines, and genres that demand different emotional states of mind?

Time management can be a big issue for me in writing across genres because fiction and nonfiction develop so differently. When I write fiction it’s like I’m planting seeds. I have some sense of what I’m planting and in the writing process I see what grows and how it grows. I know, for example, that I must write a dialogue scene between two characters. So, I do that work knowing some of what they will say to each other but leaving room for surprises as well. All this discovery can take place within one writing session.

Nonfiction writing is like digging but I don’t know what I’m digging for and I don’t know what I’ll find. Sometimes what I find takes me in unplanned and often scary directions. That discovery takes time. An essay could take weeks, even months, and I have no way of knowing what that timeframe will be. I’ve learned to be patient with myself and to give myself as much space as possible to do the thinking and searching required for such work.

Patience. I needed that reminder. Let’s talk about your new novel, Unforgivable Love, described as a “vivid reimagining of the French classic Les Liaisons Dangereuses set in 1947 Harlem.” Can you talk a little about what your earliest inspirations for it were, or the first seedling?

I still remember the first time I saw the film Dangerous Liaisons, starring Glenn Close, John Malkovich, and Michelle Pfeiffer. The story, the intrigue, the characters and their sexuality burned such an impression into my brain that I felt impelled to read the original novel by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos, Les Liaisons Dangereuses, published in 1782. After that I consumed nearly every version of the story that came down the pike including the modern-day version, Cruel Intentions, starring Sarah Michelle Gellar, Ryan Phillippe, and Reese Witherspoon. I keep a television in my office and there came this time when Cruel Intentions was in rotation on cable, and I found I was watching it repeatedly.

One day my husband came in and asked, “Why are you watching this again?” I said, “I don’t know. I think I’m going to write something.” When I mentioned this to my friend, the screenwriter Jenny Lumet, she said there needed to be a version of the story with an African American cast. That was my light-bulb moment. I knew I could do it and I knew it had to be set in Harlem in the 1940s.

I wrote it first as a screenplay but by structure a screenplay is sparse. You must leave room for the director and the actors to fill in the spaces. Only about a quarter of my vision made its way to the page. When my agent suggested I write the story as a novel, I was more than happy to do so because I could finally make that journey of discovery that is part of the novel-writing process. Unforgivable Love fulfills my original vision in both scope and story.

I had one or two chapters of Unforgivable Love written when I started at VCFA [in late 2011] but I didn’t work on it right away. I spent a semester writing short stories because I wanted to focus on the various aspects of storytelling and stretch my creative muscles by coming up with different characters and learning my strengths and weaknesses in building narrative. In my second semester I was ready to work on the novel and I completed a first draft during that semester.

Then I had to put it aside for a year! I was a dual-genre student and I spent the next two semesters studying creative nonfiction. I wrote and revised the novel a little (I did a lot of work on the North Carolina chapters during this time), but I mainly worked on writing essays. When I came back to the novel Bret Lott helped me assess where I was with the manuscript—what was missing (a lot!) and what needed revising. I just dove in and we went from there. I was able to send my agent a revised draft that semester, right before I graduated.

I’m very familiar with the film Dangerous Liaisons, but I didn’t find that I needed to know anything about the original to still become completely absorbed in Unforgivable Love, which felt fresh and original in its characterizations and setting, and that it stands on its own legs. Was this something you were conscious of when writing it?

Yes, that was important to me, to have Unforgivable Love stand on its own. With a retelling you can’t just populate the story with similar people with the same things happening and have it all make sense. I had to rebuild it from the ground up starting with my characters and learning who they were and why they might behave in such a hedonistic way. I named them and went through a process of sketching out their backgrounds, their physical characteristics, and possible motivations for how they move through the world. I left room, though, for discovery. I won’t give away any details but the character of Cecily in my novel ended up surprising me.

I also had to give them their own world. So instead of opera houses and drawing room recitals my characters have church and jazz clubs and baseball games. This helps give authenticity to the narrative.

What considerations did you have to make in writing a retelling?

The main elements I kept from the original novel involved conversations. I wanted to make sure the characters were together and speaking to each other, acting on each other as much as possible. In this story words are wielded like weapons and I wanted to keep that strategic aspect. My thoughts on this were affirmed recently when I saw the Janet McTeer/Liev Schreiber Dangerous Liaisons on Broadway and I noticed how there was a kind of tension in the audience, how people seemed to be hanging on every single word. I hope that same tension is evident in my novel.

In an early chapter of Unforgivable Love, there is this line: “Mae loved herself with a ferocity that came of feeding too hard and long on her own exquisite beauty.” Please tell, how much fun was the character of Mae Malveaux to write?! I know you personally, and Sophfronia Scott could not be more different or opposite of Mae Malveaux.

Ha! How do you know we’re opposite?

Haha!

Just kidding! But I do have respect for what it takes to create a believable villain. We all have aspects of light and dark within us and creating Mae was a matter of tapping into dark aspects of her that others can relate to: disappointment in love, a cynicism about the world, feelings of entitlement when someone has had it good their whole lives. It’s fun because I get to “go there” and think and say dark things, but the challenge is making what Mae says meaningful so she’s not a cardboard villain.

I love that phrase—“cardboard villain.” If you could put your finger on the biggest challenge of writing this book, what would it be? And how did you overcome it?

It would have to be writing certain scenes between Val and Cecily. I already knew I was playing with fire because of the conversations going on about date rape on college campuses and now we have the Harvey Weinstein scandal blowing up with issues of power dynamics and sexual harassment. There will be lots of readers who will be challenged by what happens with Cecily, but I wouldn’t have written it any differently if I were writing it today. It gets people talking and that’s what we most need to do about the way we treat each other sexually especially where issues of power come into play. We need to talk about what’s going on and how to change it.

Oh, man. The timing of your book, right? That conversation is everywhere right now on social media. And speaking of social media, at one point I saw you post a link to a jazz playlist you listened to while writing Unforgivable Love (which is a brilliant companion to help promote this story, by the way), and I wondered if you’ve always been a jazz lover, and if this is how you were drawn to the setting of 1947 Harlem in the jazz era?

I grew up listening to the blues because my father was a big fan of musicians like B.B. King and Muddy Waters. But a lot of that music crossed over into jazz and that’s how I most connected with jazz. In the early 1990s a show called “Five Guys Named Moe” premiered on Broadway featuring the music of Louis Jordan. I’d never heard of Louis Jordan before, but I loved the show because I recognized so many of the songs—“Let the Good Times Roll” and “Don’t Let the Sun Catch You Crying” and a song I’d heard B.B. King sing many times, called “Caldonia.” The energy of the show was positively contagious. I saw it three times on Broadway and once in London. I own the cast recording and I still smile and want to dance and sing out loud whenever I hear it.

I grew up listening to the blues because my father was a big fan of musicians like B.B. King and Muddy Waters. But a lot of that music crossed over into jazz and that’s how I most connected with jazz. In the early 1990s a show called “Five Guys Named Moe” premiered on Broadway featuring the music of Louis Jordan. I’d never heard of Louis Jordan before, but I loved the show because I recognized so many of the songs—“Let the Good Times Roll” and “Don’t Let the Sun Catch You Crying” and a song I’d heard B.B. King sing many times, called “Caldonia.” The energy of the show was positively contagious. I saw it three times on Broadway and once in London. I own the cast recording and I still smile and want to dance and sing out loud whenever I hear it.

As I wrote Unforgivable Love, Louis Jordan’s music was on my mind as part of the soundtrack of my character’s lives. When Val Jackson is playing baseball, the game he adores, with his friends on his aunt’s lawn I heard “Let the Good Times Roll” playing on a record in the background. When I wrote about Mae Malveaux’s desire to sweep a guy off his feet and take him to Paris I heard “Azure Te.” It was almost like I didn’t have a choice to use jazz, it was just that present in my head and in the setting. I love how jazz works in the book, it’s practically its own character.

And about the setting—I think that’s one of the elements of this book that made it feel so fresh and take on its own identity. The sense of place is alive in this story. Was there a good deal of research involved?

Most of my research involved gathering details for places and events I didn’t know enough to write them well. I lived in New York City for most of my adult life, so I already had a strong sense of Harlem. But I didn’t know anything about baseball in 1947 and what Ebbets Field looked like and the games the Brooklyn Dodgers played leading up to their appearance in the World Series in October 1947. I also researched Edith Wharton’s home, The Mount, because I wanted to use it as a model for Aunt Rose’s house. I looked at floor plans and read about the materials of the building and the choices Wharton made in designing the home. I think Aunt Rose would have made the same choices, so that helped develop her as a character.

Mainly the research came in when I wanted details the help readers feel they are moving about in the scene along with the characters.

Is there anyone outside the field of writing who inspires or influences you?

He’s not really outside the field of writing because he is a tremendous writer, but Bruce Springsteen is a huge influence on me. I’m a romantic in the same way that he is. We both have, to paraphrase his lyric to “No Surrender,” wide-open country in our eyes and romantic dreams in our heads. He also taught me how an artist works. He made himself rethink how he wrote his lyrics when he worked on “Born to Run” because his first two albums hadn’t sold well, and he knew he had to do something huge and different. I’ve also read about how he consumes music of all types, sometimes spending hours in his studio just listening to various recordings. He knows what’s being done in his field and how wants to participate in that conversation with his own spin on things. We tend to think of being an artist in terms of inspiration, but we also need to know how to work. Bruce Springsteen knows how to work, and he works hard. But he also loves what he does and it’s exhilarating to watch him express that onstage.

Stephen King talks about an “ideal reader” in his popular craft book On Writing—the person (or persons) the writer writes for. Do you have an “ideal reader” in any form?

Sometimes I have specific people in mind when I’m writing. I think, “Janet [my friend] is going to love this!” So she and anyone like her remain in my mind as the ideal reader for that particular project. It makes it fun to write when you’re writing for someone like that. It can be overwhelming if you try to write with a whole market or demographic looking over your shoulder.

I mentioned in my introduction that one of my first memories of you at grad school was the VCFA Poets and Prose softball game, and the unanimous envy of spectators over how incredibly fit you are. Now that I know you better, I know you’re an avid runner. Do you feel any connection between physicality and creativity?

This makes me laugh because if you saw me puffing my way up the hills in my neighborhood you would know I’m definitely not an avid runner! I’m hoping to purchase a spinning bike this winter because that’s my favorite mode of exercise. But I do exercise because I feel it’s important to my work to not only stay in shape, but to tend to my energy. If I’m poorly nourished and sleep-deprived I can’t string a clear thought in my head. I wouldn’t be able to write in that condition. It’s not easy—I still sit way too much during the day. But then I remember writers like Herman Melville who may have damaged their health while completing the projects of their lives. I don’t want to be like that. So, I put on my sneakers and go.

Well, I don’t care if you huff and puff up hills or not. I still would never challenge you to an arm-wrestling match.

Anyway, my final question: I swear it seems like you’ve published pretty much everything you’ve ever written. Do you have any “failed” stories languishing in your computer files that are still looking for a home? (Please say yes to make me feel better.)

I will say there are stories languishing in my computer to make you feel better! But these are stories that haven’t been submitted or are still in progress. I’m sorry to report the short stories I’ve sent out have all been published. However, there are two lengthy essays that I’ve sent out that never found a home, but they are being published in my essay collection in February so maybe those don’t count here since they will be in print?

I haven’t been able to focus on stories lately because of my book work, but I would like to write more short fiction and possibly put it together in a collection. We’ll see what happens.