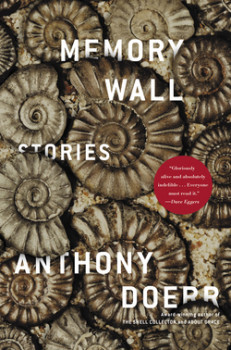

Throughout Halina Duraj’s tender and luminous debut collection of short stories, The Family Cannon (Augury Books 2014), her narrator reminds us at nearly every turn that nothing, perhaps, creates greater fidelity than pain. Whether it is an inherited, never personally-experienced kind of pain like the daughter’s in the title story whose own father was arrested by Nazis when he was just a boy in Poland, or the pain of the woman who would marry the man that boy became, or the more contemporary, first-hand kind of pain that comes with the stunning betrayal their daughter would feel decades later in an entirely different century, Duraj’s characters faithfully serve both that which is beautiful and that which is tragic. The miracle of this book, calling to mind Anthony Doerr’s recent Memory Wall, is that Duraj manages to distill the historical, cultural, familial, and interpersonal experience of love, memory, and pain in ten crystalline short stories that form a family portrait covering nearly a century, resonating both before its beginning and well beyond its end.

Throughout Halina Duraj’s tender and luminous debut collection of short stories, The Family Cannon (Augury Books 2014), her narrator reminds us at nearly every turn that nothing, perhaps, creates greater fidelity than pain. Whether it is an inherited, never personally-experienced kind of pain like the daughter’s in the title story whose own father was arrested by Nazis when he was just a boy in Poland, or the pain of the woman who would marry the man that boy became, or the more contemporary, first-hand kind of pain that comes with the stunning betrayal their daughter would feel decades later in an entirely different century, Duraj’s characters faithfully serve both that which is beautiful and that which is tragic. The miracle of this book, calling to mind Anthony Doerr’s recent Memory Wall, is that Duraj manages to distill the historical, cultural, familial, and interpersonal experience of love, memory, and pain in ten crystalline short stories that form a family portrait covering nearly a century, resonating both before its beginning and well beyond its end.

In the stunning first story, “The Family Cannon,” we find the narrator’s father, though he has reinvented himself in California well after the end of World War II, unable to escape the Nazis who nearly took his life when he was young. “Maybe I hadn’t endured four years of slave labor and maybe Hitler hadn’t come for me in the night,” the narrator thinks, “but there was a boy with whom I could have been dancing, touching hands, and it was my father’s fault I wasn’t.” Duraj’s narrator, Magda, as well as her father, is trapped between worlds, unable to escape the terror of the past in order to fully live in the present. Their urge for blame, for recompense, for some kind of freedom from long-endured suffering, is too great and searing to realize. “For once,” Magda says, “I wanted my life to stand alone, beyond comparison with monstrous things.”

Duraj’s stories move gracefully back and forth in time, tracing the life of Magda’s father, his courtship and marriage, and the subsequent birth of their daughter, who ultimately serves as the narrator for all of their stories as she strives to make sense out of who they were, how they ever came together, and who she is and will herself become. The pressure of these questions is acute early in the collection in “Witness,” where we find Magda’s father conscripted to a nursing home, his daughter struggling to suture his shaky present with his past, reading from the Polish national epic poem Pan Tadeusz:

“[T]his isn’t what he wants to hear. But I must say something. I can’t just watch this old man stare our the darkened window of a nursing home—a window that no longer shows the world he can’t go out into, but only his own body in the wheelchair, his own silent face, his close-cropped hair.”

Their family’s story is a magpie’s nest, as most of ours are. What binds it is the fierce and loyal will of the one who knows she has to keep weaving these stray bits of stick and story and trash and grass back together to make us who we are—family.

In “Survivors,” Magda declares that she hates her father, but her mother won’t allow it: “‘You think you do,’ she said. ‘But he’s your father, and you love him even if you think you don’t.’” The reader is as baffled and infuriated as Magda is: her father’s only redeeming quality, it seems, is his ability to survive. Magda turns to her mother, yearning to know how she’s lived with him all these years, and her mother’s response is beautiful and unforgettable: “She said she recited Hail Marys until she could see the vision that usually came to her: the Blessed Mother in green rubber garden boots stepping high over a pile of shit.” And in that way, these stories artfully suggest, so too might we, if we can find the right combination of protective footwear and religion.

Beyond the specific concerns of this family, Duraj’s stories are also concerned with the passage of time, even if, as in the story “Oysters,” it seems to mostly not pass. While Magda endures time with her eccentric neighbor, Miss Pierce, who has a penchant for, among other things, topless gardening, she finds herself recording the excruciating way time stretches: “I could sense forty-five minutes in the pressure of my thighs on the vinyl seat, in the slant of light coming in through the blinds. I sat on one of the yellow chairs with the cold chrome legs and toed the little black crescents where the chair had scuffed the linoleum. There was no point at looking at her clock—it had stopped long ago.” And even though, like for so many of Duraj’s arrested characters, the clocks become indifferent to the passage of time, the narrator’s own life ticks on.

Ironically, Magda’s life seems to surge forward when she spends a summer in her parents’ native Poland, where she is both exotic—as an American, and especially as a Californian—and also strangely home, albeit in a place she’s never been. The story is a jewel-like narrative that depicts the cusp of a change in her life, rather than the change itself, and, as in “Oysters,” depicts that change less in the plot than in the ephemeral passage of time: “On our long, late walk home, I could tell it was the latest Ewe and I had ever stayed out. Dawn cracked the sky open directly ahead of us. I saw a narrow ribbon of purple-tinged gold at the horizon. I inhaled that wet, tilled-earth smell. My last night, my last morning.” Even though we might strive to serve witness to our generation, or our parents’, sometimes, it seems, Duraj suggests, it is enough to be witness to the dawn.

Ironically, Magda’s life seems to surge forward when she spends a summer in her parents’ native Poland, where she is both exotic—as an American, and especially as a Californian—and also strangely home, albeit in a place she’s never been. The story is a jewel-like narrative that depicts the cusp of a change in her life, rather than the change itself, and, as in “Oysters,” depicts that change less in the plot than in the ephemeral passage of time: “On our long, late walk home, I could tell it was the latest Ewe and I had ever stayed out. Dawn cracked the sky open directly ahead of us. I saw a narrow ribbon of purple-tinged gold at the horizon. I inhaled that wet, tilled-earth smell. My last night, my last morning.” Even though we might strive to serve witness to our generation, or our parents’, sometimes, it seems, Duraj suggests, it is enough to be witness to the dawn.

This book is not about easy revelations. These characters’ lives are initially full of humor and beauty, but still haunted by the pain of both the distant and recent past. In “George Foreman Grill, George Foreman Grill,” Magda, now in her first long-term relationship, feels her mother’s love and interference: “All week long she’s been telling me to take the George Foreman grill. Jay likes it so much, she says. And all week long, I refuse. This is how it always is. If she sees I like something, she tries to give it to me. And even if I want it, I decline.” The what or the why of this negotiation, however curious and also sadly funny, is unimportant. What matters here is Magda’s sense that she is both cradled and crippled by her mother, for whom nothing ever seems to change.

In the stunning final story, “The Company She Keeps,” Magda meets her own pain. Duraj’s prose is at its most graceful and most blunt: “We take turns transferring the compost with a pitchfork, pitching the layers over into the empty side, until we get to the leaves I dumped there last fall. They cling together in shiny, putrid drifts and emit a terrible smell, a shit smell, not like the good green fertile smell of the higher layers.” She has neither her mother’s suffering patience nor the Virgin Mary’s garden boots. She has been unforgivably betrayed. In a scene as visually arresting as a contemporary take on Grant Wood’s American Gothic, she drops the pitchfork and walks away.

But walking away is never easy, and the story takes the dissolution of their relationship as seriously as it deserves. “It is possible to hurt without knowing you hurt. I hurt for months—hey guys, what about me? Pain isn’t contingent on knowledge. The knowledge is, in fact, the beginning of the end of the pain.” But throughout The Family Cannon, what ultimately abides is not what the narrator and her family and friends suffer, nor what they afflict upon one another, but rather the patient, persistent ways we can redeem one another and even ourselves through the stories we tell. At least, it seems to me, this is true for Duraj. The Family Cannon reaches, if not exactly toward heaven, always toward something brighter.