“There is no more somber enemy of good art than the pram in the hall.”

— Cyril Connolly

They say that not all those who wander are lost, but for most of my life as a would-be writer, that was bullshit. I got the writing bug at sixteen and spent the next quarter century screwing around– wandering lost from genre to genre in search of one that would define me, wandering lost from city to city and crowd to crowd as I tried to achieve some kind of career.

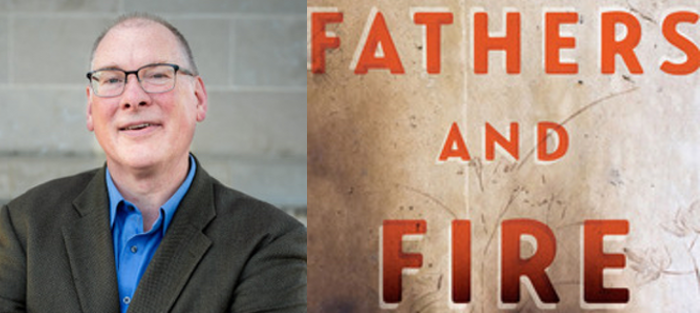

None of it worked. I published here and there beginning at the cusp of thirty, but didn’t have my first book until I was forty-two. In those intervening years, I lived in a perpetual creative adolescence, addicted to my own possibilities. I thought if I wandered into the right situation, I’d become the writer I thought I wanted to be. Instead, I achieved a stylized dilettantism high on potential and short on results.

Then one day the extended adolescence ended, and I started writing things that turned into books. What changed? I became a father a month shy of age forty-one, and my creative life took off from there. My limitless possibilities had narrowed down to the one staring me in the face. I had diapers to change, mouths to feed, and insurance to pay. What literary circle would have me now, with my exhausted eyes and the baby vomit on my sweatshirt?

Then one day the extended adolescence ended, and I started writing things that turned into books. What changed? I became a father a month shy of age forty-one, and my creative life took off from there. My limitless possibilities had narrowed down to the one staring me in the face. I had diapers to change, mouths to feed, and insurance to pay. What literary circle would have me now, with my exhausted eyes and the baby vomit on my sweatshirt?

My writing dreams looked ready to die, but something else happened instead. I stopped focusing on what I could write and started focusing on what I had to write—the things I absolutely couldn’t live without saying. I jettisoned weak projects I’d kept alive out of vanity and threw myself into the ones that felt like they could save me. My first book came out when I had a three-year-old and a one-year-old.

So when I hear see Cyril Connolly say that having kids—pram is Britspeak for baby carriage—is the enemy of good art, please pardon me for getting apoplectic. For me, not having kids turned out to be the enemy of good art. Becoming a father meant finally being forced by circumstance to claim a plot of metaphorical land where I had to dig my own ditches, cut my own trees, and build my own literary home. No crowds or cliques would make a difference. There was nothing left but me and the words that poured out of my fingers.

And oh yeah—the pram in the hallway that finally gave my life a meaning beyond my own wants.

Like many around the world right now, I’m in Covid-19 lockdown and have lots of time with my family. Too much time, if you ask my two teenage sons. Never enough, if you ask me. The lockdown has given me a chance to reflect on the ways that parenting has changed my approach to writing.

Most of the adjustments have been about writing time, which sharply decreased once I became a parent. First and foremost, I’ve learned to be flexible about my rituals. Prior to fatherhood, I was mechanistic about getting up by dawn every morning and writing for two or three hours before I faced another human being. I believed that this discipline made me a writer and that if I didn’t keep it, I couldn’t call myself a writer anymore.

Parenthood laughed at this lack of flexibility. Writing at the same time every day is ideal, sure, but I’ve had to learn to live without it. In the early days, simply getting enough sleep to be functional by dawn was a problem. Plenty of mornings I made my coffee, sat down in my chair, and fell back to sleep before I wrote a line. It didn’t take long to realize that extra sleep would do me more good than self-enslavement to my rituals. As the kids got older my weekday mornings focused on getting them ready for school, and on weekends I’d inevitably drive them to some sporting event. Unexpected interruptions regularly knocked me off track, too. I’ve settled into my writing chair only to hear a child barf in the next room, or sent them out the door to school only to realize I needed to drive them because the sidewalks were covered with sleet.

My pre-parenthood self would get the shakes at the mere thought of such damage to my writing time. But all these distractions and barriers have softened my writing discipline and made it less like bone, more like water—it flows into any shape it’s given. My writing discipline survives not because I adhere to it with heroic rigidly, but because I’ve let it learn to survive unexpected disjunctures. It’s more supple than it used to be back when nothing stood in its way, and it knows it will survive being broken and scattered.

The fragmentation and occasional destruction of my writing time has also forced me into greater decisiveness. Because I have less time to write now, I’m less likely to invest in a project I’m not sure I’m ready to write yet. Before parenthood, I’d write a draft of a novel just to see what happened and simply chuck it if it didn’t work. Now I guard my time. The development of my projects—the kneading and rising of the dough—happen in the background instead of on the page. Necessity has given me a much better nose for when a project is ready to move from notes to actual sentences, so I rarely abandon one midstream anymore.

The fragmentation and occasional destruction of my writing time has also forced me into greater decisiveness. Because I have less time to write now, I’m less likely to invest in a project I’m not sure I’m ready to write yet. Before parenthood, I’d write a draft of a novel just to see what happened and simply chuck it if it didn’t work. Now I guard my time. The development of my projects—the kneading and rising of the dough—happen in the background instead of on the page. Necessity has given me a much better nose for when a project is ready to move from notes to actual sentences, so I rarely abandon one midstream anymore.

Am I missing out on things by not writing the kind of free, exploratory drafts I used to write as a non-parent? Yes, without question—I miss the spontaneity of the old days. But I’m also gaining things I didn’t have then, because putting my projects through the gauntlet before I start writing them results in vastly stronger first drafts. Strong first drafts mean more fruitful revisions because I can pursue ways to go deeper into my material instead of asking myself if the piece even works at all. I’m also more efficient now with those revisions, not going into them willy-nilly but taking the time to formulate a set of guiding questions to ask myself while I work through the text.

I have less writing time as a parent—it’s a flat fact. I’ve got to take it when it comes, if it comes, for as long as it comes, and then use it efficiently. This lesson, learned not by choice but by necessity, forced me to become the writer I want to be: someone who puts their words out into the world in a way others can grasp.

Someday my kids will be out of the house, and time will move differently. I can see a future when my writing days start by dawn again, this time without interruptions until I’m good and ready to quit for the day. Nobody puking in the next room, nobody to drive to school because it’s sleeting out, nobody to remind about anything. Nothing but me and the imaginary voices in my head, snaking their way onto a page through my fingertips.

Maybe I’ll go back to my pre-parenthood habits of leisurely exploratory drafts, but I doubt it. Parenthood has been a valuable preparation for the loss of energy that comes with getting old. By the time my sons are both out of the house I’ll be in my sixties; I hope to be productive, certainly, but can’t fool myself into believing I’ll have the energy of my younger self again even if I have more freedom. I’ve learned so much about efficiency by having my time fragmented and rationed by parenthood, and I can’t imagine wanting to give those lessons up when the sand in my hourglass starts to run short.

If anything, I’m going to need to hone the skills I learned from being a writer/father even more. One day my bucket of sentences will make its last few descents into the well of my word hoard, and I need to be ready for it. Parenthood has given me a glimpse ahead to those days, and I don’t want to ever forget its lessons.