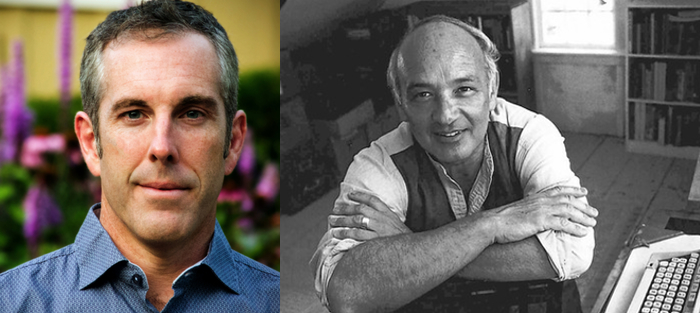

Editor’s Note: In honor of Nicholas Delbanco’s retirement from the University of Michigan, Fiction Writers Review is dedicating this week’s content to a celebration of Delbanco’s influential career as both a writer and a teacher. Delbanco is the author of nearly 30 books of fiction and non-fiction and is the recipient of numerous awards. On December 4th, a symposium entitled “The Janus-Faced Habit: The Art of Teaching and the Teaching of Art” will take place in Ann Arbor as part of a tribute to his legacy.

It begins, I imagine, without our even knowing, in a room filled with books, at an enormous table so covered with poetry journals and literary magazines I can almost feel the weight of all those words around us as we cautiously file in for our first workshop. It is a mild September evening in 2002, and we have come to the University of Michigan’s MFA program for fiction to spend the next two years of our lives writing—a prospect which seems almost too good to be true. Part of me is in fact waiting for some purse-mouthed university factotum to gravely tap me on the shoulder and tell me there’s been a terrible mistake: the invitation has been rescinded, the welcome mat put away for some more worthy applicant, thank you, goodbye. Part of me is waiting to wake up back in my former life, in a barren office overlooking three parking lots and two interstate highways, where I’m paid to process software contracts but in fact spend most of my time gazing out the window at a particularly interesting tree. Instead of working, I write lapidary little passages on oversized post-it notes meticulously describing that tree: the way the fluttering leaves flash silver as the wind passes through them. One day it might be a school of darting fish, the next day hundreds of tiny flags frantically twitching out some semaphore distress signal meant just for me. It’s a difficult thing to exactly describe, that tree, but I keep trying.

I suppose we’re all feeling pretty uncertain as we quietly find our seats. We’re all in our own way waiting for that tap on the shoulder, which surprisingly never comes. Instead, the professor arrives, welcoming us to what will be our first writing workshop at the University of Michigan. His name is Nicholas Delbanco—Nick will do just fine, he tells us—and he is, as most of us by now know, the author of dozens of books of fiction and nonfiction, a prize-winning essayist and one-time director of the MFA Program in Creative Writing. National Public Radio book critic Alan Cheuse has called him “one of our finest fiction writers,” adding: “He also happens to be one of our country’s finest master teachers.” I smile as Nick welcomes us, we’re all smiling. It’s what you do, right? You smile, and think, Is it warm in here? Am I having a heart attack? And go on smiling, through all the weeks and months to come, as the autumn days gutter out into early darkness, as the cold evening approaches when it will be my story on the chopping block.

Oh God, my story.

And God, it’s a mess, this story of mine. I just know it. Overwritten, or maybe underwritten, in every paragraph some giggly blue-eyed darling I’ve never quite had the guts to murder. It’s all middle and no end, all polish and no point, a boat without a rudder, lazily turning circles while the drooping sail drags in the water. Yes, I’ve worked like hell to get it this far, nights and days, but this far, it turns out, is still within spitting distance from the dock. And Nick will see the story for what it is—a dull, dismal failure—and then everyone else will see it, too, and that, as they say, will be that.

* * *

Writing workshops come in for a fair amount of criticism, both earned and at times just plain snarky, but what the critics all too often fail to mention is just how scary it can be to publicly share a short story or novel to which you’ve given months or even years of your life. Make no mistake, writing a good story is hard. If it weren’t, all those people you’ve met at parties, the ones who tell you they’ve got an amazing story they’ve been meaning to write, someday, would have written their amazing stories by now. Writing a short story and then having it held up in the hard light of a first-rate workshop, in a class led by a novelist whose work stretches back decades, and who’s read more and written more than you ever will, well, that’s no picnic, friend. You’re baring your heart, watching the knife flick closer, waiting for it. Yes, you need that knife—anyway your story needs it, which is why you’re here. But if at the end all you’re left with is a box full of bloody pieces and a hand in your back, pushing you out the door, what was the point?

A bad workshop is a workshop that tells you in two hundred ways, over the course of ninety minutes, why your story is terrible, but never tells you what, if anything, is good about it. It’s all whip and no mercy, and it can be a stultifyingly destructive experience for an unseasoned writer. Some writer-professors believe this to be a virtue, just as I suppose some dentists privately think drilling teeth sans anesthetic toughens us up. They have their flail, and by God you’re going to feel it.

A bad workshop is a workshop that tells you in two hundred ways, over the course of ninety minutes, why your story is terrible, but never tells you what, if anything, is good about it. It’s all whip and no mercy, and it can be a stultifyingly destructive experience for an unseasoned writer. Some writer-professors believe this to be a virtue, just as I suppose some dentists privately think drilling teeth sans anesthetic toughens us up. They have their flail, and by God you’re going to feel it.

This, it should go without saying, is a rotten way to run a writing workshop.

The right way—Nick’s way—is the way that let’s you see what’s broken but repairable, what’s weak and what already shines, and then leaves you feeling that you—yes, you—can finish the job. Because you need to believe it’s a job you’re up to, or why even bother. That’s the balance, isn’t it?

In workshop Nick always began our discussions with what was good in a story: a well-written scene, some passage of dialogue, a sharply drawn character. Yes, the story wasn’t finished, no question about that. Yes, this scene went nowhere, and yes, there were darlings that needed to be shown the door, but look at this beautiful line! Nick would say. Look how well this opening scene’s working. From that very first workshop, and every workshop that followed, he was generous and enthusiastic and above all encouraging, just when we needed it most, and so we could be generous and enthusiastic and encouraging with each other. Instead of throwing a buck-knife on the table and shouting, Last one alive wins! Nick said, This is good, now let’s make it better. In other words, he was showing us not only what it takes to write well but what it takes to be a good teacher: how we should treat our students and their stories with generosity and warmth; how, if our students have any hope of finishing their stories (and yes, it’s going to be a climb, my friend, it almost always is), we have to remind them why their story matters, we have to see the good in what they’ve done, and tell them.

Just like Nick taught us, all those years ago.