Editor’s Note: For the first several months of 2022, we’ll be celebrating some of our favorite work from the last fourteen years in a series of “From the Archives” posts.

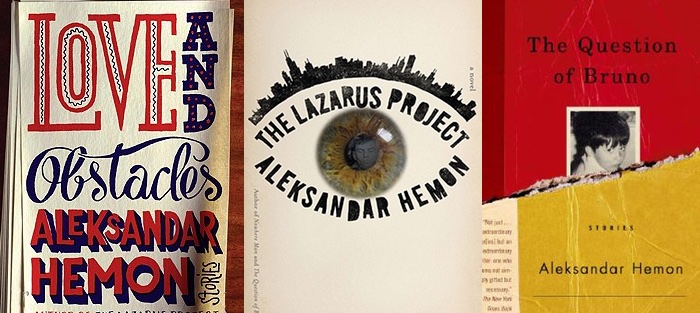

Today’s feature is an early entry in Brandon Bye’s long-running “Thoughts from the Hopwood Room” series. Here, he sheds light on Aleksandar Hemon’s 2012 roundtable Q&A. This piece was originally published on December 10, 2012.

The Hopwood room roundtable is a weekly event in which established writers discourse with the University of Michigan’s student body, faculty, and anyone in the area who is interested in writing and reading.

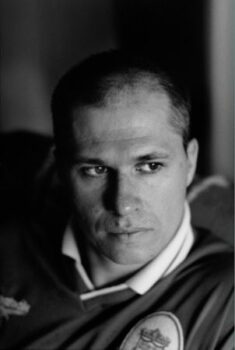

Hands behind his head, Bosnia and Herzegovina-American writer Aleksandar Hemon leaned back on the hind legs of his chair at the Hopwood Room roundtable recently and welcomed questions from the usual suspects of writers and readers, teachers and academics. “What is your name?” he asked each questioner. After a time people knew to introduce themselves before speaking. Hemon’s temperament is casual and direct in equal measure, which makes him as inviting as he is intimidating. “We can start talking about whatever you want, anytime you want. Or we can also sit in silence. I’m comfortable.”

Thirty minutes into the Q&A, with the getting-to-know-you lulls behind us, a first-year MFA student in fiction needled into the matter of influence. I paraphrase: What writers, like Kafka for European writers, linger over you when you are writing? Hemon tipped further back in his chair, nearly touching his head to the ceiling-high bookshelves behind him, and then drifted nostalgically through modern sensibility and Kafka, musing on literary imagination vs. false expertise. Ten minutes later, still working through the Kafka question, he arrived at an at-issue claim, saying:

Literature enables access to certain aspects of human knowledge that are not available otherwise. And if this were not true, there would be no reason to do it. Entertainment is not a reason to write a novel… you read a 400-page novel for entertainment, you really have a low threshold, or you are just a lonely person.

While the overture of this argument reads as if it comes from one of those Bartlett’s Familiar Quotation books, the summation of Hemon’s claim—entertainment is not a reason to write or read a novel—needs unpacking.

Talk about lingering influence. Listen for the echo of Hemon’s claim in this quote from Kafka: “I think we ought to read only the kind of books that wound and stab us. If the book we are reading doesn’t wake us up with a blow on the head, what are we reading it for? … A book must be an ice axe to break the sea frozen inside us.”

But values vary, in literature as in life. Rita Felski, prominent scholar of aesthetics and cultural studies, modernity and postmodernity, writes in her introduction of Uses of Literature (Blackwell, 2008):

We are condemned to choose, required to rank, endlessly engaged in practices of selecting, sorting, distinguishing, privileging… someone who praises a novel for its searingly honest depiction of the everyday lives of Icelandic fisherman is appealing to a different framework of value than a reader who lauds the same text for its subversive aesthetic of self-shattering.

Hemon’s framework of value hinges on a personal assembly of social fissures and cultural pressures. He, as is the case with you and Kafka and me, cannot and do not favor all texts equally. We inevitably find some stories more impressive, more relevant, more wounding and stabbing, more marvelous and pleasurable than others. And just as we are moved by different texts for different reasons, we write and read different texts for different reasons. Swooning women contributing to and scrolling through web pages of Antonio Banderes Harlequin-romantic fan fiction carry the same currency, in some ways, as Harold Bloom and Joseph Campbell inching through and theorizing over Finnegans Wake. The border Hemon defends between literature and entertainment risks dividing literary readers and writers from common readers and writers, as if the former is absolutely superior to the latter. In Felski’s chapter Enchantment, she meditates on this bisection:

Given the sheer impossibility of getting inside someone’s head to judge the quality of their aesthetic experience, any attempt to create a moral taxonomy of types of reader or viewer absorption—to make sweeping distinctions between authentic enchantment and baleful bewitchment—would appear to be based on little more than the reflexes of class prejudice.

From lab reports to murder ballads, Olympic-athlete documentaries to mixed media art installations, New Yorker cartoons to 400-page novels, form and genre should not be thought of as hindrances to knowledge, but rather points of access. Can’t both high and popular art cater to a desire for wonder and mystery, to an experience of knowledge, particularly the knowledge of oneself and the world beyond the self, through enchantment, perhaps, that is not available in everyday life? Given the chance, I think Hemon might say, yes, of course (mea culpa for not asking at the Q&A), my use of literature is a use of literature not the use of literature. The swapping of the definite article for the indefinite makes all the difference. So while Hemon’s approach to the use of literature might most closely resemble Kafka’s ice axe, other writers and readers will perhaps choose hatchets or hair dryers. Yet each are probing into some part of the soul, excavating what it means to be human, whether that exploration lies along the surface or resides at the core.