Editor’s Note: The Hopwood Room Roundtable is a weekly event in which visiting writers of the Helen Zell MFA Program in Creative Writing discuss their work and the writing life with the University of Michigan’s student body, faculty, and the local literary community.

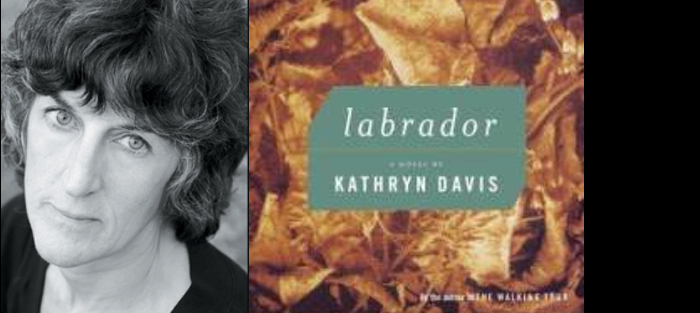

Despite the ongoing gloom of this Midwestern winter, Kathryn Davis filled the Hopwood room with writers eager to ask her questions. Davis told us that she loves answering reader questions. “You never know what somebody’s going to ask you.” It seems simple now to write this out, but I suppose you never know what you really think about a given matter unless someone—and as a writer, as Davis knows, that someone is often you—asks.

Despite the ongoing gloom of this Midwestern winter, Kathryn Davis filled the Hopwood room with writers eager to ask her questions. Davis told us that she loves answering reader questions. “You never know what somebody’s going to ask you.” It seems simple now to write this out, but I suppose you never know what you really think about a given matter unless someone—and as a writer, as Davis knows, that someone is often you—asks.

During the roundtable discussion, Davis described what an ideal ending might feel like: “a door opening up, a door slamming shut, a window being closed, someone falling down a hole, someone wandering off in the distance… I want to feel that there’s room, and things are humming in some way.” She compared the way she thinks about her character’s desires to “constructing a piece of music… where there’s going to be a sound and it’s going to continue and that sound might degrade into another sound or shift registers. Sorts of transitions occur.” Writing a novel, she said, is like first falling in love (with an idea), and then working very hard at staying in love. And on her daily writing habits:

When I’m home in Vermont, I write every morning, and if I want to, I’m allowed to take a weekend off… I’m not allowed to read during my writing time. I’m allowed to have some coffee. I used to be allowed to have cigarettes, but I’m not allowed anymore. Isn’t it funny how artists all became artists because they didn’t like people telling them what to do? And then what do you have to do when you’re an artist? You have to tell yourself what to do, and you really have to listen. And isn’t that hard? But, that’s what I do.

When asked how her novel Versailles (Back Bay Books, 2003) came to be, Davis told us about visiting Versailles with her daughter. On the grounds of the historic French palace, Davis said that she felt the way she always feels when she’s going to write about something, even if she hasn’t realized it yet: enchantment. “I sort of felt like I had fallen in love. I had that same really hyper charged-up feeling that I didn’t understand the source of.”

When asked how her novel Versailles (Back Bay Books, 2003) came to be, Davis told us about visiting Versailles with her daughter. On the grounds of the historic French palace, Davis said that she felt the way she always feels when she’s going to write about something, even if she hasn’t realized it yet: enchantment. “I sort of felt like I had fallen in love. I had that same really hyper charged-up feeling that I didn’t understand the source of.”

To end the roundtable discussion, host and author Michael Byers asked Davis to talk about throwing away her first novel and then getting it back again (Labrador, Mariner Books, 2000). “First,” she said, “you never waste time when you’re writing. You could write 500 pages of something and decide it isn’t good, but the time you spent is not wasted. Something is going on even though sometimes it feels awful.” Davis detailed the first iteration of Labrador, which in truth sounded pretty interesting, and asking her first readers, “is this boring?” To her surprise, she received praise from her readers, but could she trust it? “Just like in relationships, you’re told you’ve got to work at a long-term project. It’s not always going to be easy. There are going to be problems.” But when do you admit the thing is just not good?

To end the roundtable discussion, host and author Michael Byers asked Davis to talk about throwing away her first novel and then getting it back again (Labrador, Mariner Books, 2000). “First,” she said, “you never waste time when you’re writing. You could write 500 pages of something and decide it isn’t good, but the time you spent is not wasted. Something is going on even though sometimes it feels awful.” Davis detailed the first iteration of Labrador, which in truth sounded pretty interesting, and asking her first readers, “is this boring?” To her surprise, she received praise from her readers, but could she trust it? “Just like in relationships, you’re told you’ve got to work at a long-term project. It’s not always going to be easy. There are going to be problems.” But when do you admit the thing is just not good?

In the instance of Labrador, I had a dream. I was living in the middle of nowhere Vermont. In real life, not in the dream, I had a barn and horse in it. In the dream, I was going out to the barn to take some oats to the horse, and the top of the barn door opened in a way that it didn’t in real life, and this horse stuck its head out. It wasn’t my horse. It was… it was Mr. Ed. And he looked at me and he said, it’s boooorrrriinngg. And that was how I knew.

The room poured over with laughter. Davis described the intense relief she felt once she abandoned Labrador, which she put in a box, meaning to tote it along in the next move. She never saw it again. But many years later, after a surge of inspiration from an old Ingmar Bergman movie, Davis started to write what became Labrador 2.0, a completely different book from that first thrown-away draft.

Whether it’s a failed relationship or a failed first novel, the things you learn in the process of failing aren’t failures themselves. In the writing life, as in love life, baggage can serve as an advantage if it’s carried the right way. That’s revision.