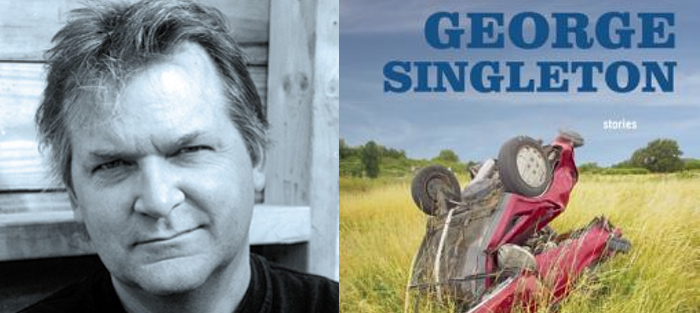

My last two collections—Stray Decorum (Dzanc Books, 2012) and Between Wrecks (Dzanc Books, 2014)—were intended to be one. In my mind, I had two parts to the original project. In Part I, a character named Stet Looper would narrate stories about his exploits in regard to finishing up a low-residency master’s degree program in Southern Culture Studies, at a fictional institution of higher learning called Ole Miss-Taylor. Part II involved stories told in both first-and third person, wherein Stet Looper appeared as a minor character. The collection ran 430 pages. My long-time agent said, “No one’s going to publish a 430 page collection of stories by you.” Then she added that she didn’t even want to attempt selling any collection of mine until I wrote a novel that she liked.

I got another agent. This one said, “Write what you wish to write! Don’t spend time trying to outguess what publishers want! I’ll be happy to try to place a collection of your stories, but I have to tell you—no one’s going to publish a 430 page collection by George Singleton.”

This second agent was the late, magnanimous Kit Ward. She divided the original manuscript into two halves—one that featured strays, one that featured personal disasters—and did not flinch when I asked her to send them to Dzanc. I had long tired of hearing, “Well, we’ll do a collection after a novel” from other, larger Houses.

The whole reason I started writing about this character Stet Looper came through an odd alignment of blunders. At Harcourt I had a wonderfully bright copyeditor named David Hough. He called one day in about 2006 to say, “Hey, George, my mom’s sick in Minnesota, so I’m going to have to subcontract your novel [Work Shirts for Madmen (Mariner Books, 2008)] to a woman up in New York.” He went on to say how this woman worked at the New Yorker at some point, and that she was in her eighties.

I said, of course, “Tell your mom I said hey, and that I hope she recovers well,” because that’s what we say in the South.

I said, of course, “Tell your mom I said hey, and that I hope she recovers well,” because that’s what we say in the South.

This must have occurred right before all those confounding track changing programs appeared, for this new copyeditor mailed me the hardcopy, marked up like all get-out. The novel is a first-person narrative, told by a native southerner with a college degree. He’s an artist of sorts. He says things like, “I only wanted to get in my truck and take some curves fast,” and “I only needed to get to the liquor store before my wife got home,” and “My wife only cared that my liver healed properly.” For better or worse, it’s how people talk here, and—I suspect—most places where sane people congregate.

The old woman transposed the “only”s and the verbs: “I wanted only to get in my truck and take some curves fast,” “I needed only to get to the liquor store before my wife got home,” “My wife cared only…”

I wrote “Stet” in the margins. A lot. Normally, I’m pretty sure, I work well with editors. I venture to guess that about 95% of the time editors are correct in their thinking and I’m wrong. But this particular character—his name’s Harp Spillman—isn’t an Oxford-educated artist living in South Carolina.

To make matters worse, on one of these transpositions the copyeditor thought it necessary to write in the margins, “Do you people in the South not know this rule of grammar?”

I wrote, “I want only to kill you,” below it.

And then I went on a Stet-fest. Hell, if this haughty woman had changed “nwrwieurw” to “meteorite,” because my fingers shifted over a notch, I would’ve written stet in the margins out of meanness. The manuscript might’ve been three hundred pages. I had 180 stets.

And then I went on a Stet-fest. Hell, if this haughty woman had changed “nwrwieurw” to “meteorite,” because my fingers shifted over a notch, I would’ve written stet in the margins out of meanness. The manuscript might’ve been three hundred pages. I had 180 stets.

To jump ahead, I sent the marked proofs back to David Hough, his mother got well, and he called me up to say, “I had a feeling that wasn’t going to work out. I’ve kept all your stets.”

Not long afterwards I came up with this: I am going to invent a character named Stet, just so when his name shows up in the manuscript an editor or copyeditor will stop and wonder if I meant the character, or if I wanted to let something stand.

I don’t have many other hobbies in South Carolina.

So. Although the stories have been scrambled in order, and although there aren’t two parts to one gigantic unsellable collection (which I wanted to call No Cover Available, but that’s another story), Stet survived. I have that old, well-meaning copyeditor to thank. Or I have my ex-copyeditor’s mother to thank. I need to thank someone. I only want to thank someone.