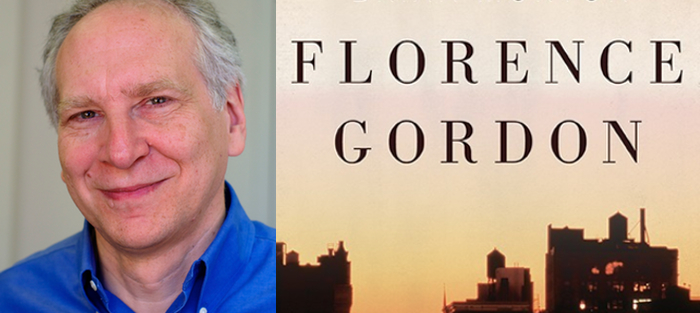

Decades ago, when I was in college, I had a writing teacher who told his students to “write the novel you want to read.” I’ve been trying to follow this advice for almost forty years now, but it’s not as easy as it sounds.

The advice conjures up a picture of a novelist rubbing her chin thoughtfully and dreaming up a book. “I wish I could read a novel about a young woman who meets the fiery anarchist Emma Goldman and becomes a labor organizer. And then she meets the young Eleanor Roosevelt and they have a torrid affair. And in the end she has to make a choice—will she become a revolutionary like Emma Goldman or a reformer like Eleanor Roosevelt? I wish I could read that novel—and, by gum, that’s the novel I’m going to write!”

It would be nice if it worked that way. But for me—and, I suspect, for many other novelists—the process is somewhat different. You thoughtfully rub your chin and decide that you’d like to read a novel about an idealistic young woman who meets both Emma Goldman and Eleanor Roosevelt, and you start your novel with that idea in mind, but within fifty pages, your idealistic young woman has turned into a bank robber, and Emma Goldman has turned into a getaway car, and Eleanor Roosevelt has turned into a bagful of cash, and although you’ve never had much interest in reading novels about the criminal underworld, you seem to be writing one.

Once, when I was three or four years into the writing of a novel, I looked through a notebook I’d kept while I was working on the first draft. The notebook contained questions like, “When Paul visits his father, do they talk about Ingrid? When Ingrid goes to Canada, does she meet the monk?”

Reading these entries years later, all I could think was, “Who’s Paul? Who’s Ingrid? Who’s the monk?” I was on the tenth or eleventh draft at that point, and I couldn’t remember any of these characters at all.

Novelists are always talking about how characters “got away from them.” But the phenomenon I’m talking about is different. It’s not characters going in directions you hadn’t anticipated; it’s characters vanishing entirely, and being replaced by characters who have little do with the story as you’d originally conceived it.

Novelists are always talking about how characters “got away from them.” But the phenomenon I’m talking about is different. It’s not characters going in directions you hadn’t anticipated; it’s characters vanishing entirely, and being replaced by characters who have little do with the story as you’d originally conceived it.

Writing a novel—for me, at least—is like answering a craigslist ad placed by a group of people seeking a roommate. You meet them; you like them; you move in; but within a short period of time, all of them have moved out, and new people have moved in, and these new people, it turns out, are the ones you’re going to live with for the next few years.

I began my first novel, The Dylanist, shortly after my father died. I wanted to write an autobiographical novel about a father and a son. But somewhere along the line, the character who was based on me disappeared, and a young woman took his place. At first I wasn’t pleased about this—I thought I had a lot to say about fathers and sons, and I didn’t think I had anything to say about fathers and daughters. But when I tried to write about the character based on myself, the novel kept stalling, and when I wrote about the young woman, the novel moved forward. A novel about a father and daughter was evidently what wanted to be written, and the only choice I had was whether to write it or write nothing at all.

At the time, this seemed like an odd little hiccup, probably attributable to the fact that I’d never written a novel before. But as I continued to write them, and watched the same thing happening again and again, I realized that it wasn’t an inexplicable glitch in my writing process—it is my writing process.

The title character of my new novel, Florence Gordon (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), is a seventy-five-year-old feminist intellectual and activist. I never planned to write about a character like this; she just turned up. I’m happy that she turned up—it meant, for one thing, that I got to spend three or four years in the company of a character who was smarter than I am. But when she first showed up on the page—strong-minded, grouchy, and, I got the feeling, skeptical about whether I was worthy to write about her—she came as a complete surprise.

The title character of my new novel, Florence Gordon (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), is a seventy-five-year-old feminist intellectual and activist. I never planned to write about a character like this; she just turned up. I’m happy that she turned up—it meant, for one thing, that I got to spend three or four years in the company of a character who was smarter than I am. But when she first showed up on the page—strong-minded, grouchy, and, I got the feeling, skeptical about whether I was worthy to write about her—she came as a complete surprise.

The central relationship in the book is between Florence and her nineteen-year-old granddaughter, Emily. When I saw that I was writing a novel about the wary coming-together of a grandmother and granddaughter, I was puzzled but interested in how things would turn out. After decades of writing, when a novel starts to emerge that isn’t the novel I’d thought I was going to write, I don’t question it anymore. I try just to stay out of its way.