Editor’s Note: For the first several months of 2022, we’ll be celebrating some of our favorite work from the last fourteen years in a series of “From the Archives” posts.

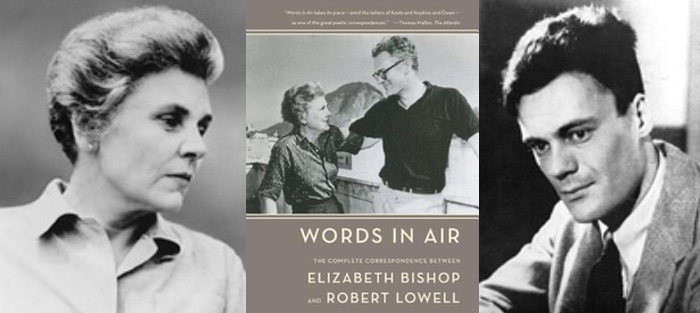

In today’s feature, Charlotte Boulay meditates on Words in Air, the collected correspondence between Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell, and the way reading shapes both our writing and lived experience. This essay was originally published on June 13, 2011.

The Reader: A Creature of Habit

1. Aspirations and reassurances

From the beginning, I’ve felt like a bit of an imposter as a contributor to this site, whose title suggests that its reviewers may be fiction writers themselves. I’m a poet. I tried to write short stories in college, and they were not very good. Some were truly terrible. And yet I read fiction every day. I read some poetry most days, but fiction, always. I love narrative, and characters, and paragraphs; I just don’t write that way. And many of my fiction-writer friends read poetry. Does it go without saying that we should all be reading both? Holding fiction and poetry up to each other might function as the kind of comparison Anne Carson describes in her amazing book Economy of the Unlost:

With and against, aligned and adverse, each is placed like a surface on which the other may come into focus. Sometimes you can see a celestial object better by looking at something else, with it, in the sky.

I once promised myself that I wouldn’t start reading books about reading books, because it seems like exactly the kind of wormhole I might get stuck in for far too long, but I do love reading lists. I love Goodreads, which lets me look back and reflect on a year of reading, and which is currently telling me that I am seven books behind my goal for the year. Is this helpful? Probably not. I feel behind in my reading anyway much of the time.

A friend of my mother’s calculated the speed at which she reads and then the number of books she finishes in an average year. She came to the conclusion that she didn’t have time for potboilers—not if she wanted to read deeply and well for the rest of her life. This approach to reading seems admirable but also makes me anxious and sad. I love potboilers AND literary fiction. In different ways, could I consider them both reading “well”? In addition, this approach seems to take the pleasure out of reading, much the same way Joe Queenan’s book-a-day adventure seemed to me, or Paisely Rekdal’s attempt a few years ago to read five books of poetry a week. Her account is actually a highly entertaining read, though a response from poet and critic Stephen Burt is one I return to for some reassuring and practical advice on actually reading lots of poetry.

Even though I’ve sworn off Francine Prose and her ilk, I can’t seem to get away from thinking about what it means to have a reading list at all. My current favorite reading about reading is contained in Words in Air, the collection of Elizabeth Bishop’s and Robert Lowell’s letters to each other, in which they often discuss what they’re reading, which turns out to be everything. Bishop and Lowell sustained a correspondence over thirty years, 459 letters in all.

Even though I’ve sworn off Francine Prose and her ilk, I can’t seem to get away from thinking about what it means to have a reading list at all. My current favorite reading about reading is contained in Words in Air, the collection of Elizabeth Bishop’s and Robert Lowell’s letters to each other, in which they often discuss what they’re reading, which turns out to be everything. Bishop and Lowell sustained a correspondence over thirty years, 459 letters in all.

If I love a book, fiction or poetry, then in an interview with an author, I’m just as interested in how they answer the question “what are you reading?” as in other details of how they created the characters, etc. What I’m not saying here: feel like you have to read as much as Elizabeth Bishop and/or Robert Lowell. Or, read everything that they read. What I am saying is that while I sometimes feel overwhelmed by the many things I need or want to read, the way these two poets talk to each other about reading is so wonderful that it makes me feel enlivened and refreshed.

In 1960, Bishop wrote to Lowell:

You ask if I have ever found “reading and writing curiously self-sufficient.” Well, both Lota and I read from 7 a.m. intermittently until 1 a.m. every day, and all sort of things, good and bad…And then I’ve always had a daydream of being a lighthouse keeper, absolutely alone, with no one to interrupt my reading or just sitting—and although such dreams are sternly dismissed at 16 or so, they always haunt one a bit, I suppose.

Dozens of letters (and hundreds of books) later, we find Lowell in 1962:

I’m either getting soft, or good books are suddenly pouring out. K. A. Porter’s huge novel [Katherine Anne Porter’s Ship of Fools], very grim, and the only long novel since The American Tragedy [Theodore Dreiser] that needs to be long…Randall’s essays are very dashing and satirical and sad…Then Wilson’s Civil War book [Edmund Wilson: Patriotic Gore], his best I think, with Plutarchan portraits of Lincoln, Grant, Justice Holmes, etc. Then Alfred Kazin’s great heap of essays, surprisingly tougher and less long winded than he is…(Oh, and wonderful, Isherwood’s new novel, particularly the end) [Down There on a Visit].

And in the same letter another great listing account, this one of poets:

Damn the young! My students, after I gave them a laborious six weeks on Pope, Dryden, Dr. Johnson, Goldsmith, etc. turned out to have read only one poet before Hopkins—Donne, of course. I feel taken in the flank. I am all pointed to explain the new poetry as a continuation, change and revolution of the old. But no one reads the old, except English professors. I’m on a Wordsworth and Blake jag. I’d like to do poems that would hit all in one flash, though loaded with subtleties of art and passion underneath. Or great clumsy structures like Wordsworth’s Leech Gatherer, that somehow lift great sail and catch the wind [Wordsworth, “Resolution and Independence,” 1807].

I stand reprimanded. I will go review my Dryden at once. (My Donne also, why not?) But how these lists reassure and stimulate me is their ambition. Of course we must all read the art of our own time. And, equally, of course we must read the poets before Hopkins, and after him. And then we must read some more. But instead of seeming didactic or overwhelming, in the context of the letters these lists are entirely natural and funny. And don’t think, well sure, if I lived in my Brazilian retreat (like Bishop) I could read Dryden whenever I wanted—read the letters. There are plenty of children and construction projects, and mental breakdowns, and travels in there as well. It’s the clarity of why to read certain things that stands out:

But isn’t it strange how those Rimbaud sonnets (early poems, that is) sound so gay and healthy and normal beside Baudelaire?

As well as the complete and total integration of the art of reading and writing with the rest of life:

(And have you read Art and Illusion by one Gombrich?—it is fascinating.) I find it is time to go to market. What kind of plan do you have for your opera, or is it an opera? Now you must teach Harriet to swim—or have you? It is just the age to learn. I believe in swimming, flying, and crawling, and burrowing. (Bishop, July 27th, 1960)

Here is Bishop on the hardboiled novelists of her time:

I wonder if you’ve read all of Raymond Chandler?—I like him better than Dashiell Hammett—real poetic, sometimes.

And Bishop on Salinger:

I HATED the Salinger story. It took me days to go through it, gingerly, a page at a time, and blushing with embarrassment for him every ridiculous sentence of the way. How can they let him do it?…Perhaps Seymour isn’t supposed to be anything out of the ordinary, nor his poems either, so that all that writhing and reeling is to show the average man trying to express his love for his brother, or brotherly love? Well, Henry James did it much better in one or two long sentences.

I suppose this isn’t a surprising opinion. Bishop, who wrote fiction herself—you can read it in her Collected Prose—would not have admired Salinger’s style, or his showy intellectual references. She was concerned with accuracy, both of description, and of emotion. Perhaps I wouldn’t have been so impressed with Franny and Zooey if I had read Henry James first. Or perhaps it’s impossible to be impressed with Franny and Zooey if you read it for the first time as an adult.

Lowell writes:

Your Brazil has lovely Bishop touches, the humor of the opening, and everywhere you seem to dampen the hollow enthusiasm of the man who comments on the pictures…Then like Moby-Dick and Paradise Lost, those long stretched of organized information, which I wonder at and envy…

I would never have thought to compare Bishop’s Brazil poems (published in the first section of her book Questions of Travel) to Moby Dick, not least because I haven’t read Moby Dick; it’s been on my long list forever. But it’s just one instance of many of the line between fiction and poetry blurred, or perhaps one instance that shows very clearly how, to these two poets, in terms of what was vital and interesting, no line was there at all.

While Lowell and Bishop are both frequently hilarious, they are also huge gossips. Bishop, a bit isolated in Brazil, sometimes takes particular pleasure in news of other writers:

In the last N.Y. Review I see a long interview with Sartre, on his 70th birthday—perhaps you’ve seen it?…and whether one likes him or not, he says some really interesting things about his life, friends, approaching blindness & so on. (Apparently he is almost blind—but of course has had only one eye all his life, to begin with.) But can you imagine a worse fate for your declining years than being read aloud to by Simone de Beauvoir? Always loyal—nevertheless, he does say she “reads too fast.” Coitado!1

One of the many wonderful things about letters is they can give as wide a range of voices as a busy, interesting novel. It’s good to have Lowell’s manic lists and Bishop’s dry, chatty wit running around in my head, as well as some of their more sorrowful letters, recounting struggles with finances, illness, love, and writing.

2. One way of coming into focus

I dislike winter. One winter when I lived in Michigan I decided to try to embrace the season. Instead of huddling in whiny complaint, I would immerse myself in wintry novels. I read Orhan Pamuk’s Snow, a literal-minded first choice. I started Anna Karenina, thinking to wallow in the descriptions of the wintry Russian plains, but abandoned it. I finally read it last summer, in the midst of a heat wave. It wasn’t exactly a failure of synchronicity, though, because unsurprisingly Russia has many seasons—as scenes of Levin enthusiastically scything the fields on his estate show. I don’t know why I equated it with winter. I keep trying to make my favorite writers match the seasons: spring—Keats. A sticky August—C.D. Wright’s Deepstep Come Shining; late summer rains—Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things. Sometimes it works better than others, but that’s my own little push-back against the “must-read” lists, my way of organizing what cannot, and probably should not be organized. This summer I’m looking forward to David Grossman’s To the End of the Land, for no other reason than the book’s cover is scattered with hot, bright poppies.

For now I’ll jump ahead to autumn, which always brings to mind one of Robert Lowell’s most famous poems, “Skunk Hour” (dedicated to Bishop). You probably already know it, but it will stand to be re-read again this year. I think of it every time I pass a coitado skunk crushed on the highway, or when I call the cat inside in the evenings and that pungent scent is on the breeze. Here is an excerpt:

A car radio bleats,

‘Love, O careless Love . . . .’ I hear

my ill-spirit sob in each blood cell,

as if my hand were at its throat . . . .

I myself am hell,

nobody’s here—

only skunks, that search

in the moonlight for a bite to eat.They march on their soles up Main Street:

white stripes, moonstruck eyes’ red fire

under the chalk-dry and spar spire

of the Trinitarian Church.I stand on top

of our back steps and breathe the rich air—

a mother skunk with her column of kittens swills the garbage pail

She jabs her wedge-head in a cup

of sour cream, drops her ostrich tail,

and will not scare.

What a cast of characters! Chief among them, the poet himself, worried about his mind, in his own hell, alone except for the skunk performing her fierce, absurd, frightening, motherly scavenging. That’s fall all over—panicky and mean, coming on despite anything we do.

I’m more likely to re-read Bishop in the spring—the wonderful “The End of March.” For fall, “The Moose” always comes to mind. But it’s “Five Flights Up,” the final poem in Bishop’s last book, Geography III, that actually takes place in autumn, the season she died, on October 6, 1979, of a sudden brain hemorrhage, alone in her apartment, after writing a letter.

Perhaps it helps to know a little of Bishop’s biography to understand this poem fully: that she had lost her lover, Lota, to suicide some years earlier, and that she experienced other significant troubles. It’s a poem that speaks in Bishop’s usual precise, sincere language about the passage of time, and the difficulty of reconciling the past with the present.

But perhaps you don’t need to know any of that. Perhaps you are sitting in your room, trying to write, early in the morning, and the small, ordinary details of the scene taking place outside as the darkness slowly recedes gently lead you, too, to an awareness of something larger, whether it comes to you in lines that stretch to the right margin or otherwise. Here is an excerpt to close:

Still dark.

The unknown bird sits on his usual branch.

The little dog next door barks in his sleep

inquiringly, just once.

Perhaps in his sleep, too, the bird inquires

once or twice, quavering.

Questions—if that is what they are—

answered directly, simply,

by day itself.