Each year the Elizabeth Kostova Foundation selects five native English speaking (NES) writers and five Bulgarian writers to participate in the Sozopol Fiction Seminar, which takes places in the tiny, historic town of Sozopol, Bulgaria, on the Black Sea. And this summer I was lucky enough to be chosen as one of the NES fellows. Joining me were Kodi Scheer, Lana Santoni, Maya Sloan, and FWR contributor Steven Wingate (our “Quotes and Notes” columnist). Our Bulgarian counterparts were Alexandra Chaushova, Evgeny Cherepov, Maria Doneva, Yanitsa Radeva, and Alexander Shpatov. For one week last month we lived together (literally—each NES fellow shared a room with one of the Bulgarian Fellows), shared meals together, discussed writing together, and discovered the odd similarities in our work and our lives. It was, in a word, amazing. And though I’m by no means a photographer, I hope that a few of these snapshots might begin to capture the experience of being in such a unique place with so many generous and talented individuals.

On the morning of June 4th, having flown into Sofia the night before, we rendezvoused outside The Ministry of Sport to board a small bus bound for Sozopol. In addition to the fiction fellows, we were joined by a dozen other publishers, editors, translators, and novelists. Among them were John O’Brien, founder of Dalkey Archive Press; Little Brown editor Reagan Arthur; Croatian-born fiction writer Josip Novakovich; Emilia Dvoryanova, a novelist and professor at New Bulgarian University; and Georgi Gospodinov, editor of Literaturen Vestnik and, most recently, the author of Natural Novel. The 500-kilometer journey would take most of the day as we traveled east across nearly the entire country. For some reason I was expecting an unfamiliar landscape out the windows as we drove, yet much of Bulgaria reminded me of the American West—foothills, mountains, and agricultural plains.

Steven Wingate upon our arrival in Sozopol

Eight hours later, when we finally arrived, I was relieved to reach Sozopol, not least of which because many Bulgarians drive as if the Red Army has just returned. Let me say that you haven’t really lived until you’ve watched a sedan decide to pass three semis on a narrow, two-lane road while a gas truck barrels in a downhill approach from the opposite direction. Luckily, I’d been seated next to Reagan Arthur, who shares my gallows humor, and we were able to laugh through much of the trip.

But in Sozopol, a different pace of life persists. One that is inspiring not only for its leisurely approach to living, but also for its beauty. There are cobblestone streets that wind lazily between the buildings, and beyond the terra-cotta rooftops the Black Sea sparkles in the distance.

But in Sozopol, a different pace of life persists. One that is inspiring not only for its leisurely approach to living, but also for its beauty. There are cobblestone streets that wind lazily between the buildings, and beyond the terra-cotta rooftops the Black Sea sparkles in the distance.

View out the back of my room at the Hotel Diamanti

Walking to the art gallery where most of the seminar events took place

The beauty of Sozopol was exceeded only by the generosity of its inhabitants. After we’d had a chance to settle into our rooms at the Diamanti Hotel, we walked down to a regal, two-story building overlooking the water. It had once been a school, but since 1991 has served as an art gallery. (Sozopol has always been a haven for visual artists, so having a writer’s conference in this town was a natural fit.) We would spend much of the next five days here, participating in roundtable discussions on publishing and translating, conducting workshops, and listening to craft lectures. But at that first night’s reception we were treated like diplomats or dignitaries. After a welcome address by members of the board of directors and a wonderful faculty reading by Emilia Dvoryanova and Elizabeth Kostova, the mayor of Sozopol, Panayot Reizi, greeted the participants and bestowed each of us with flowers as tokens of the city’s hospitality.

Georgi Gospodinov, Emilia Dvoryanova, Yordan Kosturkov, Reagan Arthur, Elizabeth Kostova, and translator Boris Deliradev during the Welcome Address for participants

Elizabeth Kostova reads a selection from her forthcoming novel, The Swan Thieves, with her Bulgarian translator, Yordan Kosturkov

Kodi Scheer after the welcome ceremony. To her left, Maya Sloan speaks with Alexandra Chaushova (facing camera).

Elizabeth Kostova with Milena Deleva, Managing Director of EKF

The patio of the Diamanti hotel

After the opening events, we headed back up to the Diamanti for dinner. We had most of our meals here, which were served outdoors on an airy patio overlooking the sea. The breeze came up from the water, and you could watch fishing boats slowly heading out to deeper water as you ate. There were crepes and hard-boiled eggs and pastries for breakfast, fresh vegetables and cucumber soup and moussaka or stuffed peppers for lunch. And, of course, Shopska Salata—cucumbers, tomatoes, peppers, and grated sirene cheese (think feta but not as crumbly or quite as briny), seasoned with oil and vinegar and parsley.

Breakfast at the Diamanti

But whether we were eating at the Diamanti hotel or elsewhere, each of the meals were inspiring. Our dinners, in particular, were long and leisurely, often stretching late into the night. Fresh fish and even fresher vegetables filled the tables. As did the ouzo and rakia, a Balkan spirit made from distilled plums or grapes, similar to grappa. And it was during these lengthy meals as the sun set and the stars emerged that we spent much of our time talking and getting to know one other.

Dinner overlooking the sea

Me with Kapka Kassabova and Georgi Gospodinov (photo Credit Yanitsa Radeva)

And while writing was, certainly, at the heart of much of what we discussed during our meals and days in Sozopol, our conversations were as diverse as the participants themselves. In addition to the publishers, translators, faculty members, and fellows, there were many distinguished writers from around the world who’d come as guests, including Rawi Hage, a Lebanon-born photographer and fiction writer who lives in Montreal, author of DeNiro’s Game, which won the 2008 Dublin Impac award, and Cockroach; Canadian fiction writer Madeleine Thien, also from Montreal, author of Simple Recipes and Certainty; Kapka Kassabova, a Bulgarian-born poet, essayist, and fiction writer who lives in Scotland, author most recently of Street Without a Name; and David Stromberg, a writer and artist living in Jerusalem, author of several collections of single panel cartoons, including Baddies, Saddies, Confusies, and Desperaddies.

Alexandra Chaushova and David Stromberg

Kapka Kassabova, Elizabeth Kostova, Georgi Gospodinov, Julian Popov, Manol Pekykov, Rawi Hage, and Madeleine Thien

But despite the beautiful scenery and the wonderful food, the focus of the seminar truly was on the practice and process of writing. There were workshops in the morning, roundtable discussions in the afternoon, and lectures in the evening.

NES Workshop participants, from left: Kodi Scheer, Steven Wingate, Maya Sloan, Lana Santoni, and faculty member Elizabeth Kostova

Bulgarian workshop participants, from left: Maria Doneva, Evgeny Cherepov, Alexander Shpatov, Yanitsa Radeva, Alexandra Chaushova, and faculty member Emilia Dvoryanova (photo credit Yanitsa Radeva)

And due to the international nature of the conference, many of the talks centered on issues of translation—translation as an art form, the process of editing fiction in another language, how authors reach an international audience, and the scarcity of foreign titles in translation in English.

John O’Brien, Reagan Arthur, Julian Popov, Bozhana Apostolova (founder of publishing house Janet 45), and Anthony Georgiev (publisher of Vagabond) discuss ways of creating readership for authors

Highlights also included a reading and craft talk by Josip Novakovich on overcoming obstacles in the writing process, and a lecture about embracing uncertainty in our work, entitled “What are Our Books Made of,” by Georgi Gospodinov.

Participants during one of the afternoon roundtable discussions. From left, Steven Wingate, Alexandra Chaushova, Alexander Shpatov, me, and Madeleine Thien (photo credit Yanitsa Radeva)

But the culminating experience of our time in Sozopol was the Fellow’s reading at the end of the seminar. Despite the fact that we’d lived, eaten, and participated in lectures and roundtables together for most of a week (to say nothing of riding across the country together on a bus), we hadn’t yet had the chance to hear one another’s work. Prior to our arrival in Bulgaria, however, we’d each been asked to submit a sample of our writing to be translated for this final event. We would each present our own work, and then it would be read in translation by one of the other fellows. My roommate, Evgeny, and I were paired together for the event. Initially, I’d expected the experience to be one of novelty—how often does one have the chance to hear one’s work in translation, let alone in Bulgarian? Yet spoken by Evgeny, my work didn’t sound particularly foreign at all. In fact, I was surprised by how easily it was for me to follow the story. Everyone laughed at the right places, and he inhabited the piece with ease. Then, as soon as I heard him read his own work in Bulgarian, the story of his I was about to deliver in English came alive for me as well—the cadence and rhythm of his reading translated meaning as much as the words themselves.

Me and my roommate, Evgeny Cherepov

And so this was how we spent our days—quite literally immersed in the practice, discussion, and consideration of fiction. From the individual engaged in the solitary act at his desk to the public figure standing at the lectern on tour presenting her work to the public, it seemed we touched on each aspect of this thing we call “The Writer’s Life.” Though after our time living by the sea together, Sozopol felt more like the writer’s dream.

Addendum

Anthony Georgieff with Boyana Petrova, owner of Nissim Bookshop, on Levski Boulevard. Petrova’s father, Valeri Petrov, is the Bulgarian translator of Shakespeare’s complete works

For more about the 2009 Sozopol Fiction Seminar, as well as the literary tradition and current state of publishing in Bulgaria, please see my essay “Art in Translation,” which appears in the July issue of Vagabond, Bulgaria’s English Monthly. Vagabond is published by author and photographer Anthony Georgieff, who among other generosities was kind enough to not only give several of us a wonderful walking tour of Sofia on our last day in the city, but to also offer me the opportunity to write this piece for his magazine.

Further Resources

Yantisa Radeva, one of the 2009 fellows, covers this year’s seminar in Bulgarian for Mastilo.info. She will also have an essay about the event forthcoming in Literaturen Vestnik.

Beginning this fall, Dalkey Archive Press at the University of Illinois will be offering several fellowships for translators of fiction from other world languages into English. Rhett MacNeil, one of the 2009 Dalkey Translation Fellows, was a participant at this year’s Sozopol Fiction Seminar.

The Red House Centre for Culture and Debate

The Red House Centre for Culture and Debate was once the home of the Bulgarian sculptor Andrey Nikolov. But in recent years it has been renovated and converted into a multi-use building housing an art gallery, a bed & breakfast, and a restaurant. The Elizabeth Kostova Foundation also has offices on the premises.

The two primary publishers of literature in Bulgaria are Ciela Publishing, whose director, Svetlozar Zhelev, is co-founder of The Elizabeth Kostova Foundation, and Janet 45 (for English translation, click here), directed by Manol Peykov.

Parting Shots from Sofia

Saint Alexander Nevski Church in Sofia

Sofia University

Remnants of the Soviet past

The Graffiti reads ‘The Last Supper’

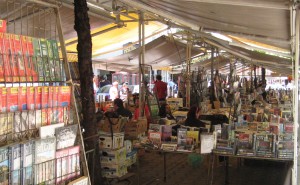

Bookstalls on Slaveikov Square

The American Corner in Sofia

Introducing the 2009 Fellows Reading at the American Corner in Sofia

Alexander Shpatov reading at the American Corner in Sofia

Kodi Scheer reading at the American Corner in Sofia

Translator Boris Deliradev talks with 2009 fellows Yanitsa Radeva, Maria Doneva, and Maya Sloan.