A Critique of Brian Kiteley’s The 3 A.M. Epiphany

There is something wrong with the way we currently teach creative writing. Almost all the creative writing teachers I have met have been diligent and well-read; it is not a problem of effort or commitment. The problem is how we see creative writing, a philosophy or ideology that we have all to a greater or lesser extent bought into. As ideologies are generally invisible, in order to point out the flaws of this particular one, I have to critique a concrete example of it, and for this purpose have chosen Brian Kiteley’s book of writing advice and fiction prompts, The 3 A.M. Epiphany.

There is something wrong with the way we currently teach creative writing. Almost all the creative writing teachers I have met have been diligent and well-read; it is not a problem of effort or commitment. The problem is how we see creative writing, a philosophy or ideology that we have all to a greater or lesser extent bought into. As ideologies are generally invisible, in order to point out the flaws of this particular one, I have to critique a concrete example of it, and for this purpose have chosen Brian Kiteley’s book of writing advice and fiction prompts, The 3 A.M. Epiphany.

My disagreement with Professor Kiteley is simple. In The 3 A.M. Epiphany, he says, “The most damning criticism I’ve heard of workshops is that they promote mere competence.” Au contraire, the most damning criticism of workshops is that they do not promote competence.

Creative writing pedagogy cannot be effective as long as we see competence as a pejorative, as something to be bypassed or ignored. Creative writing needs a new sense of what “competence” should mean.

Learning by Prompts

I would not have been so bothered by The 3 A.M. Epiphany were there not so much in it I admired. Kiteley distils years of writing instruction into a collection of annotated prompts, offering via theory—at the beginning of each chapter—and practice—the exercises—a complete vision of the working artist. Kiteley argues that we learn best by doing. Through prompts ranging from straight forward (“Use a particular and fairly vivid piece of clothing to tell a story”) to wonderfully taxing (“Use the letters of the first names of four or five ex-boyfriends or ex-girlfriends as your only alphabet for a very short story”), a novice can build up a toolkit and an accomplished writer can add to one. Kiteley is persuasive on the method:

All the other arts—as well as athletics, obviously—take the notion of practice and exercise very seriously. Too many writers make a fetish of the natural, untroubled writer who just breathes out a great story.

Kiteley is right to question our obsession with the supposedly “natural” writer. Hemingway and Keats did not behave like natural geniuses; they carefully accumulated skills and continually sought out advice.

Kiteley also argues for another (rather troubling) benefit of writing prompts: they push writers out of artistic comfort zones. “These exercises,” he explains, “try to respond to how writers censor themselves, how we react to familiar patterns of behavior, and how we fall into ruts.” I’m sure I’m not the only teacher who has read a student’s story, seen its deep flaws, and yet known with an uneasy sense of wonder that I would have never imagined writing a story like it—not from that premise, not with those ingredients.

We keep doing the same thing without knowing it, and we can never be sure if we are deepening into a particular style or withering within its limits. It seems, therefore, that there are different forces at work in writing, forces that sometimes conflict. There is the deep well from which creativity comes, a source never under our full conscious control, and while we need skills to do something with this creativity, sometimes these skills can damage or confine at the same time as they teach.

Kiteley wishes to startle and coax aspiring writers out of these confines. In The 3 A.M. Epiphany, he lauds the unusual over the expected, the idiosyncratic over the conventional. In his section on “Internal Structure,” he comments, “This set of exercises should help you break with the tired idea of linear progression.” He aims to “derange” students’ stories, to push their work into new, wilder places, to “enable them to build more personal or individualized fiction rather than what sometimes feel like cookie-cutter stories.”

Kiteley’s comments throughout The 3 A.M. Epiphany build an archetype of the typical student story: it carelessly switches POVs, has a linear plot with few surprises, lacks irony or depth, and is rife with pedestrian language. Kiteley’s solution? Push the student and her story into greater maturity by grafting new material to the work (new material produced through writing exercises), and using his authority and insight—and the strangeness of the prompts—to bypass the student’s censoring, blinkered ego (which loves safe and small). Stories are meant to be unique and personal, but through laziness and fear we exchange our bard’s harp for a cookie cutter, stamping out the same work over and over.

The Missing Middle

Kiteley’s approach probably produces good results: a workshop with him would be a powerful experience. But I wonder what a student does after the semester ends, with no teacher to “derange” their fiction, to say if the latest wild addition works or not. Kiteley advises writers to be the final judge of their stories’ quality, but this leaves them back where they started. Kiteley’s stress on experimentation probably helps his ex-students seem more mature in their writing—they know more tricks—but he skips a crucial stage.

Student writers, via this method, progress from a novice sensibility to an expert one, going from “cookie cutter” to “individualized” work—but no other art mints experts without first tackling competence. Competence involves an understanding of how one’s art works. And developing this understanding is by no means simple or automatic. I didn’t have it when I began my MFA, and I’d wager this is true of most.

Earlier, when I spoke about the unconscious as a “well,” I misled you. The metaphor of the unconscious as a well implies the artist does not have to work: you pull water from a well and hand it to someone to drink. In reality, whatever we pull from our psyche’s dark places must be cooked, shaped, laboured over. Art, in other words, can fail. If it didn’t, writing classes would be unnecessary. If we think of writing as writing-for-a-reader, then we desire to communicate, to show another person our deep imaginings. Part of what we mean by an “unfinished” piece is a failure of communication—meaning and sensation gone missing or messy. Whatever you wanted me to feel, I didn’t. Or we say something “ejects” us from a story, or bores us in a novel: we expect fiction to transport us somewhere and keep us there.

Before we can teach our students how to produce “unique” stories, we first have to teach them how to make this communication happen, how to get the magic started.

Starting with Tradition

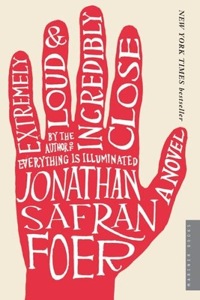

Surveying modern literature, we can draw two conclusions about how fiction performs its magic. On the one hand, great writers can do anything, and there seems no limit to the shapes their fiction takes. See: Samuel Beckett. On the other hand, it is also true that there are recurring forms and conventions really seem to work. One pleasure of reading Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close or The Age of Innocence is the anticipation of what comes next. We know the sort of tale it is. Conventions give readers a framework to decipher and anticipate; they give authors a literary Lego set. A convention says that if “x” happens, the reader will register it and think, “Ah, this is the type of story I’m reading. Now I predict ‘y’ is coming.” Form, therefore, gives the writer tools for subversion and subterfuge.

Surveying modern literature, we can draw two conclusions about how fiction performs its magic. On the one hand, great writers can do anything, and there seems no limit to the shapes their fiction takes. See: Samuel Beckett. On the other hand, it is also true that there are recurring forms and conventions really seem to work. One pleasure of reading Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close or The Age of Innocence is the anticipation of what comes next. We know the sort of tale it is. Conventions give readers a framework to decipher and anticipate; they give authors a literary Lego set. A convention says that if “x” happens, the reader will register it and think, “Ah, this is the type of story I’m reading. Now I predict ‘y’ is coming.” Form, therefore, gives the writer tools for subversion and subterfuge.

Fortunately for us teachers, fiction has a central form, traceable back to Gilgamesh, which we call a “story,” and which we can boil down to: a character in some kind of trouble. The protagonist wants to get out of trouble, but doing so is not easy; in the process, something important happens, something significant changes. No trouble, no story. Consider Chekhov’s “The Lady with the Little Dog,” Poe’s “The Tell Tale Heart,” Chopin’s “The Story of an Hour,” James’s “The Beast in the Jungle,” Hemingway’s “Indian Camp,” Baldwin’s “Sonny’s Blues,” Cheever’s “The Swimmer,” Malamud’s “The Magic Barrel,” Wolff’s “In the Garden of the North American Martyrs,” and Gen’s “Who’s Irish?” When you mention at a cocktail party that you write fiction, this is the kind of thing your listener imagines (or hopes) you are writing.

Students do not write dull stories because of inhibition, or lack of creativity (at least not always). Students produce dull work because they attempt to write a conventional story, the kind that has hooked audiences for millennia, without knowing how. They can’t pull off a classic story because writing a good one—like nearly everything worth doing in life—is so much harder than it seems.

When Kiteley calls linear stories “tired,” recommends writing “against tradition,” and resents “cookie cutter” fiction, this reveals in him a disdain for competence. That disdain is not unique to him. It infuses that bastion of the MFA, the workshop. What Kiteley’s book says explicitly, the workshop says implicitly: bring in your fiction, whatever it is, however you think it works, and we will tell you if it is good or bad. We will then help you make your story appear to be written by an expert. But we’ve skipped a stage—what a “story” is, and the assembly of its various parts.

A Muddled Method

The irony is that Kiteley, despite his dislike of “tired” linear progression (tired for whom?), still admires the traditional story’s virtues. He affirms the necessity of “character, plot, language, and surprise,” and argues against omniscience because it reduces suspense. This final strange claim—one of the most suspenseful novels ever written, The Count of Monte Cristo, employs an omniscient narrator—begs the question of how one does create suspense. The word suggests an onlooker held aloft, hooked. The reader encounters something so significant it snares him, becoming both a helpless victim and willing participant. Actually learning how to rapidly exposit, evoke sympathy, present setting, create conflict, put a character’s values at risk (and invent obstacles that increasingly challenge those values) is difficult. It is what we should teach in fiction classes.

Kiteley’s ambivalence toward suspense—both affirming its centrality (“the writer’s most important tool”), while offering prompts that conspicuously ignore it (“Create a smart character. Show us this character’s unusual intelligence;” “Write a story about a ghost who is bored by the immensities of time and timelessness”)—illustrates the muddle that is creative writing today. Goals and methods clash.

Our goal is ancient: produce work that people – ideally many people – will pay money to read (this goal increases in urgency and visibility as graduation nears). Yet our methods serve other interests. Students arrive with high esteem of their unique sensibilities; teachers arrive respectful of idiosyncrasy, independence, newness. The workshop allows both these outlooks to be validated, a place where the teacher pretends that simply by inductive observation and taking notes on everyone’s constructive criticism, students will osmose how to write a masterpiece–where the students pretend that bombardment from classmates, and the instructor’s pearls of wisdom, will teach them how not to screw up next semester.

In such a world, “competence” is merely a pejorative: has the writer has demonstrated the outward trappings of storytelling—dialogue, characterisation, sentence-craft? Is the shield that defends the story from criticism sufficiently ornate? But the work seems merely competent because there has not been an equal amount of interest and training in the mechanisms of stories, of what lies beneath.

Learning How to Cook

Kiteley is correct that workshops offer an incomplete model. He offers, in The 3 A.M. Epiphany, a valuable way to improve them. But he continues to subscribe to their underlying philosophy, that students arrive with story know-how already in them, and the teacher merely points out flaws and suggests remedies. But students don’t, by and large, have stories in them—they arrive with ingredients, but they haven’t learned to cook. Over a semester or two, this teaching method leaves students feeling bruised but hopeful, eager to return to the workshop’s heady cocktail of mysterious censure and praise, and secretly delighted that there isn’t anything external to themselves to learn about writing—apparently anything can work if you do it right. Over an entire program, however, it leaves them dissatisfied, feeling “done with workshops,” yet still artistically dependent on their now distant teachers, and almost as confused as when they arrived.

Before talk of solutions, a note on “tradition.” One can espouse traditional story structure, even attribute wonderful, mystical properties to it (as I privately do), and simultaneously respect, enjoy, and admire experimentalist fiction—without contradiction. After all, experimenting implies a move away from something. The traditional story is that something. Teachers should not care what students write twenty years later for their sixth book, but how to help them write their first. The question is not what they should write but what we should teach. And while an openly experimentalist workshop makes sense, what lacks sense is splitting the difference, which is the pitfall of The 3 A.M. Epiphany and most workshops. Students write narrative fiction of some kind, with no agreed rules and vocabulary for this fiction. One can try out anything and see if the workshop likes it.

The trouble is the conventional story has rules. The writer may approach these intuitively or consciously, but regardless, they are there. They may be mere conventions, but considering they predate written language, calling them so seems a trifle disingenuous. One needs no hocus-pocus to teach these techniques: screenwriters, for instance, have extensively catalogued “plot” (cribbed from playwrights), and the best of their books provide real, measurable help to an aspiring writer. James Wood’s How Fiction Works provides an admirable entry point to the study of third person limited POV; Francis and Bonniejean Christensen’s Notes Toward a New Rhetoric offers a complete system for teaching a particular kind of prose style. There are many other examples.

Teaching in the Daylight

More importantly, if the teacher focuses on traditional story techniques, one learns they cover nearly any particular story’s idiosyncrasies. “Rising tension,” for instance, applies to most student stories. If we teach classic storytelling, then we no longer need to reinvent the wheel for each submission: we explain terms up front, and apply those terms over a semester. Students, unless extremely advanced, need not produce “individualized” stories. They need to know how to competently produce the standard ones, and practice to master them.

With such teaching, the nature of a writing class changes. Under the workshop model, students enter the class in daylight (they submit what they want), but end in twilight and mist (their peers dislike their stories for a bewildering host of reasons, and their teacher’s brilliant advice feels like enigmatic divination). Writing this way really is a three a.m. epiphany because a writer essentially has to wait around until inspiration strikes. If you assume this approach, then Kiteley’s book is an excellent aid. It shortcuts the waiting. But I propose the opposite: refuse the students’ initial work—however much it will annoy them—and instead first teach them the vocabulary and tools of their art. This makes the workshop experience coherent, as the teacher can then show these techniques at work in one submission after another, demonstrating how they empower story upon story.

If we teach in daylight, with as little mystery as possible, we give students models for how to produce any number of successful stories. The three p.m. epiphany occurs in the cloudy afternoon light of a classroom filled with mundane talk of the structures underpinning intelligent, suspenseful fiction. This is teaching them to cook.

A clean, well-lighted creative writing pedagogy takes the risk of telling students the truth: there are things about their craft they need to learn. And it assumes the responsibility of getting aspiring writers to be “competent”—confident and skilled in the traditional principles of their art—so that they can then spend their writing careers composing their own unique place in the house of fiction.

Further Links & Resources

- Curious about the book in question? Brian Kiteley’s The 3 A.M. Epiphany, and the sequel, The 4 A.M. Breakthrough.

- One of the playwright’s plot books Wallace had in mind: Write That Play, by Kenneth Thorpe Rowe.

- Suddenly feel the need for some classic stories to read and take apart how they work on the page? Stories We Love.

- An opposing view in an interview with Lance Olson over at HTML Giant.