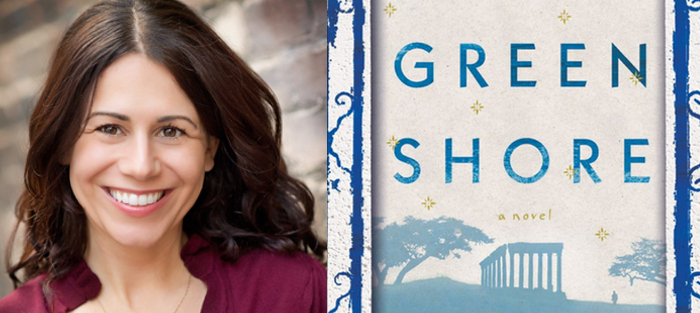

Though in some ways I got to know Natalie Bakopoulos through the experience of reading her debut novel, The Green Shore, it was on the shore of Bulgaria’s Black Sea coast earlier this summer that we first truly met. She was reading in an art gallery in the Old Town of Sozopol, as part of the conclusion of the Sozopol Fiction Seminars, where she’d been one of the 2013 English-language fellows. Outside, the sea waves crashed against the rocks, as if following the rhythm of her story.

“I’m half Greek and half Ukranian, but I live in America,” she would tell me several days later, holding a glass of wine. Yet even without knowing her background, her wide smile could not hide her warm Eastern European temperament.

The Green Shore, which was published by Simon & Schuster in 2012 and is just out in paperback in the US, is set during the military dictatorship of Greece (1967-1973), which her father’s family lived through. Earlier this year it was translated by Pavel Talev and published in Bulgarian by Ciela Books, under the title Зеленият бряг. In addition to her first novel, Bakopoulos has published work in Granta, Salon, the New York Times, Glimmer Train, Ninth Letter, and Tin House. Her short fiction has received a 2010 O. Henry Award, a Hopwood Award, and the Platsis Prize for Work on the Greek Legacy.

But despite her many successes and literary recognition, Bakopoulos did not set out to be a writer. She received an undergraduate degree in zoology, and then entered graduate school for physiology. It was only after working as a research assistant for several years that she admitted this desire to write. So she began working for a science journal as an editor, getting closer to the process, while writing her first stories on the side. Then, in her late twenties, she applied to the University of Michigan’s MFA Program in Creative Writing, where she was accepted.

However, Bakopoulos does not regret the years spend in science, because she thinks that there is a great deal of commonality between science and literature: “In both disciplines you have to be creative, you have to ask questions,” she says. “In science, you pursue something and then in the end you realize that what you are pursuing is not working, and you start over. It’s just like writing.”

Bakopoulos and I spoke in Sofia after both attending a public editing session by Richard Beard, writer and Director of the National Academy of Writing in Oxford, England. The event was a part of CapitaLiterature, a series of literary happenings in Sofia, sponsored by the Elizabeth Kostova Foundation. We chatted in the Red House garden restaurant.

Interview:

Your first novel, The Green Shore, tells the story of the revolutionary events that happened in Greece between 1967 and 1973. How did you decide to write about this place and this time?

Your first novel, The Green Shore, tells the story of the revolutionary events that happened in Greece between 1967 and 1973. How did you decide to write about this place and this time?

My father is from Greece, and I always wanted to write about Greece. The novel starts the night of the coup that brought the dictatorship, which took place on April 21st of 1967. In May of that year, there were supposed to be Greek elections. The person who was thought to win was George Papandreou. He was centrist, popular, and beloved. His son Andreas, on the other hand [who was a member of the Greek Parliament and an advisor to his father], was radical; many Greeks did not like him, and his radical views also made the American CIA very nervous. So, there were rumors that year that the elections would not happen because there would be a coup. No one knew if the coup would come from the left, from the right, from the king, or from the army.

What happened, surprisingly, was that the colonels—rather than the generals higher up—were the ones who pulled it off. In the middle of the night they arrested politicians, lawyers, journalists, artists, poets—mostly those with left-leaning views.

Following the coup, numerous freedoms were taken away, parts of the constitution were suspended, books were banned, and anyone found on the street after curfew was shot. People were scared. They didn’t know what was happening, how long it would last, or what they should do. There was a lot of fear.

So, this is the background of my book. I chose this era because it was a time of change, a time of politics, and the time when Greece was entering the modern era.

Also, my father’s uncle was a poet named Mihalis Katsaros. He was a left-wing poet and very political. I started reading about him and his work, and I realized he would be a great character—at least, a man like him. I had never met him, but I imagined him as a part of this story

Did you structure the novel in advance, or did you just begin writing?

I wish I were that organized! As far as the structure, it was just sort of trial and error. There are four main characters, and each has a voice: Mihalis, the poet; his sister, Eleni, a widowed doctor; and two of her three children—her daughters Anna and Sophie. So, when I felt interested in Anna, the youngest character, I’d write scenes from her point of view. Then I’d think, “Oh, how would Sophie react to this?” And I’d begin writing from her perspective. It became a giant mess.

So to sort things out, I hung a bulletin board in my room and wrote the names of each character– Anna, Sophie, Mihalis, and Eleni—on different colored pieces of paper. Then I started to draw lines between scenes, tracing what each character’s life looked like, how they were interacting with one another, and how they related to the world and its historical events. It was a visual way of seeing the book develop. But as far as mapping, it wasn’t possible—I had to write through it.

You were not born when these historical events that you write about happened. So weren’t you afraid of the reaction of Greeks who had been living at that time?

Absolutely, I was worried about this. I was particularly worried about the reaction in Greece, because I am Greek-American, not Greek. (Actually, the book was first published in Greece. They were quicker than my publisher in the US.) But philosophically, I feel that a novel is an act of the imagination. I am not a historian; I am a novelist. So, my primary concern is the lives of the characters and how they see the world.

In the public editing session with Richard Beard that we just attended, he said, “Plot is a blueprint of human behavior.” That’s brilliant! It’s not a sequence of events; it’s how characters perceive the world. You asked me about structure, and originally I did attempt to make a structure. I said, “Well, here is Anna. I need to get her from 1970 into 1971, and then this has to happen.” I was thinking in terms of time and everything felt very forced. Then, I started to think about the character without that structure. Suddenly Anna made a bad choice, and then another bad choice, or a good choice, or whatever, and that was a plot. That’s how I started to structure the novel. It felt more organic. I realized that a character’s behavior creates the plot.

You have an MFA from the University of Michigan, where you now teach creative writing classes. Do you think that one can learn how to be a writer at the university?

Well, yes and no. When someone asks me: “Can writing be taught?” I say: “That’s what I am doing for a living, so I hope so.” But the question is a good one. Not everybody can be taught to write, because you have to be teachable, you have to be someone who wants to write. So much of it is reading, and so much of it is revision, and so much of it is just imagination. You can have all the technique in the world, but if you don’t have interesting ideas then it’s going to go nowhere. Similarly, you can have all the big ideas in the world, but if you don’t have the technique, it’ll also go nowhere.

My number one job is to inspire a love of reading. Number two, I have to show students that their voices are important—that at the age of twenty you have as much to say as when you are forty or sixty. You just start saying it differently. The third thing is that you have to be able to force yourself to do the work. You can be the most talented kid in the world, but if you’re showing up to class not doing the work, it’s not going to happen. As a teacher you can try to teach young writers how to stimulate their imaginations, how to have the discipline to write, and how to learn the technique to pull it off. But I don’t think that everyone is teachable. There must be an active desire; learning is never passive.

Nowadays, when everybody talks about money and commercial success, how can you explain the importance of art, literature, and writing?

Oh, I wish I knew! I think for those who don’t find it that important they’ll probably go to business school and make a lot of money, and do something else. I have students who are from wealthy backgrounds, who grew up with people just like them, and who have never had to really work. They have vacations and houses and they think that other people are poor just because they don’t work hard. This makes me crazy. It’s because they don’t have the experience. By reading about people who are not like you, from places that are not like yours, from different racial backgrounds, from different socio-economic backgrounds, from different cultural backgrounds, you become a better person. Literature allows us to understand how people live. It teaches empathy. I think this is the most important thing in life, to have empathy.

What was the thing that most impressed you about spending time in Bulgaria and about Bulgarians? What kind of differences in mentality did you find between Bulgarians and Americans?

I love so many things about the country. I love the way the language sounds. And because my father’s Greek and my mother is Ukrainian, I felt very comfortable in the culture.

I love so many things about the country. I love the way the language sounds. And because my father’s Greek and my mother is Ukrainian, I felt very comfortable in the culture.

What I also like about Bulgaria is that it is very much Balkan, in a good way. People don’t really care much about rules, and I’m drawn to that. There’s something here about the questioning of authority that I like. If there’s a rule, people are going to question it! If someone who is in power says something, everyone’s going to fight it. There’s less rigidity here.

Also, the way we think of time here is different. For example, if we have a meeting at six o’clock, at six we say, “Should we go now or maybe 6:30?” Whereas, the Americans are ready to go right on time. I identify more with the former—it seems very laid back, warm. There is such warmth in the culture here that I felt immediately.

You are working on a new book now. Could you tell us more about it?

Yes. I’m working again on a novel. It is also set in Athens, but contemporary – during the economic crisis. It begins during a garbage strike and is the story of a Greek-American woman who’s living there. I think that’s all I can say about it now.