Georgi Gospodinov has been a primary player in Bulgaria’s literary emergence over the past decade, steadily gaining recognition in Europe and now in North America. An exceptionally omnivorous writer, he is equally at home in poetry, fiction, and theater; he has written screenplays, essays, and a graphic novel. He is also active as an editor, with two anthologies out on the experience of living under Socialism in Bulgaria. If you’re like me and believe that writers who work in multiple genres and ceaselessly reinvent themselves are intrinsically more interesting, then Gospodinov is your kind of guy.

As a fictionist, he first earned recognition in the US for Natural Novel [translated into English by Zornitza Hristova and published by Dalkey Archive Press, 2005], which established him as a writer able to weave together many moods—from disgust to tenderness and everything in-between—in a polyphonous patchwork instantly recognizable to readers of postmodern and flash fiction, accustomed to the interplay of perspective. Gospodinov followed this up with the similarly-toned short story collection And Other Stories [translated into English by Alexis Levitin and Magdalena Levy and published by Northwestern University Press, 2007).

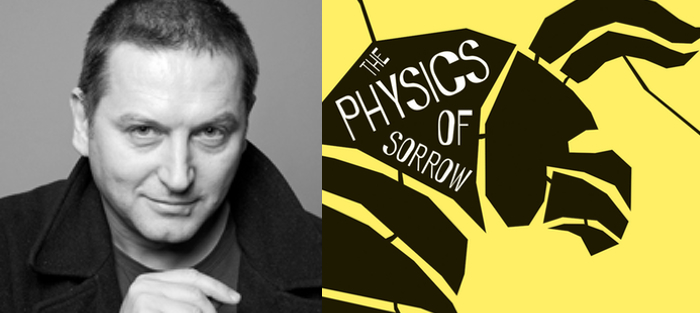

The Physics of Sorrow—translated by Angela Rodel and published by Open Letter Books earlier in 2015, and reviewed in The New Yorker by Garth Greenwell—is a heftier book that feels more like a novel in both the hand and the mind. It is a book conceived as a labyrinth, full of loops and tangents that create their own tangents; in this way, it very much follows on his previously translated fiction. But it differs from the others in offering more opportunities for readers to get to know its protagonist—named, like its author, Georgi Gospodinov. This protagonist has the gift of being able to enter into the emotional life of others, which gives his author more opportunities to share the rhythms of human experience with readers. In Physics Gospodinov uses the same principles of refraction and polyphony as he did in his earlier works, but to a more clearly empathetic end. In the hallways and hidden rooms of his book are people we will not forget, because they are people who will not forget each other.

Gospodinov is in the US this fall as part of the Bulgarian Fiction (NY)ghts series, and will speak at the Bulgarian consulate at 7pm on Wednesday, September 23. He will also be reading and in conversation with Alberto Manguel at Community Bookstore at 7pm on Thursday, September 24. He is well worth checking out—and even seeing if you’re in New York—not just because his literary star is rising, but because he is capable of surprising himself, and that surprise rings across his pages.

Interview (translated from the Bulgarian by Angela Rodel):

Steven Wingate: “I can’t offer a linear story because no labyrinth and no story is ever linear,” says the narrator of Physics, who shares your name. In the world of digital literature, this is a foundational concept that we call multiform, multi-variant, or polylinear narrative. In the US we have the traditions of metafiction and postmodernism, but I suspect that you didn’t have much exposure to those authors as a young writer in Bulgaria before the fall of Communism. How did you arrive at this polylinear conception of narrative, and are there any literary precedents that drew you to it?

Georgi Gospodinov: The 1990s were truly an important and formative decade in Bulgaria. We were learning the simple things that had previously been forbidden to us—how to speak in a new everyday language, different from the clichés of socialism. You had to have been previously immersed in that language to sense what an important change came about after the fall of the Wall. Also, during the ‘90s all those authors you were asking me about appeared in Bulgarian, both the postmodernists and Foucault, who was very important for us. OK, so they came to us decades late and in another, post-communist context, but perhaps that made them even more important to us. They already had another, political meaning—postmodernism included. I was in my twenties and had the freedom to try everything; I also had another important right—the right to fail. It was then that I wrote Natural Novel (1999), where I tried that nonlinear structure for the first time. I called it “faceted,” because I used the fly’s eye and its faceted structure as a model. In the novel there was a separate “Natural History of Flies.”

Georgi Gospodinov: The 1990s were truly an important and formative decade in Bulgaria. We were learning the simple things that had previously been forbidden to us—how to speak in a new everyday language, different from the clichés of socialism. You had to have been previously immersed in that language to sense what an important change came about after the fall of the Wall. Also, during the ‘90s all those authors you were asking me about appeared in Bulgarian, both the postmodernists and Foucault, who was very important for us. OK, so they came to us decades late and in another, post-communist context, but perhaps that made them even more important to us. They already had another, political meaning—postmodernism included. I was in my twenties and had the freedom to try everything; I also had another important right—the right to fail. It was then that I wrote Natural Novel (1999), where I tried that nonlinear structure for the first time. I called it “faceted,” because I used the fly’s eye and its faceted structure as a model. In the novel there was a separate “Natural History of Flies.”

Why is that facetedness and nonlinearity important to me? First, because life itself, especially during the 1990s, was like that. The classic novel offers structure which life actually doesn’t have. And therein lies its trick, its temptation and its comfort. To read about life as something that has design, continuity, and destiny. I’ve never liked that about novels. That’s why my Natural Novel had to be natural. Chaotic and crazy, fragmentary and breathless or filled with pauses, during which nothing in particular happens, besides life itself. Second, I’m coming from poetry [Gospodinov’s first book, a collection of poetry, Lapidarium (1992), won the National Debut Prize, and his second poetry collection, The Cherry Tree of the People (1996), received the Best Book of the Year Prize from the Bulgarian Writers’ Association] and in a certain sense I’ve always felt like a smuggler of poetry into prose. Both of my novels owe a lot to poetry, in terms of language and structure. The third explanation for the wacky structure of my novels—and I’ll end with this—is that they are coming on the heels of the huge social experiment that was socialism, and which every totalitarianism is. There the monumental was put on a pedestal. But I want to write anti-monumental novels.

The novel’s narrative conceives of itself spatially; it calls itself a labyrinth and it’s a bit like a living house, with “cellars” and stories hidden within its “corridors.” Gaming and fantasy fiction communities also conceive of narratives as a places to visit, or “storyworlds” where multiple tales unfold. Do you see a connection between that and your geospatial conception of narrative in Physics? And is there something in the Zeitgeist that is bringing that idea to the forefront of creative culture now?

I must immediately admit that I am pretty far removed from fantasy and gaming. So in that sense I didn’t have them in mind as formative spaces in the novel. In the house that is this book, there is also a basement and a ground floor, which was important to me as I was building the narrative. Is this connected to the Zeitgeist? Yes, in some strange way. During socialism, many people in Bulgaria, including my family, lived in those basement rooms, because it was cheaper and there wasn’t enough housing for everyone. As a child, I really did spend whole days by myself at home next to a street-level window, slightly sunk into the ground, and saw the world as feet and cats. This image and experience became the basis for the novel.

Game designers talk about “top down” projects, which start from an idea of how they’ll be executed and fill in the characters and details, versus “bottom up” projects, which start from character and details and gradually figure out how they’ll be executed. What kind of project is Physics? Did you start “top down” with a concept? “Bottom up” with a voice and set of images?

If we enter into that spatial matrix, I started from the “bottom up,” through the voice and through various scenes. The Boy and the Minotaur were there from the very beginning. Over the course of writing, somewhere near the middle, the idea of accumulation, lists, and collections grew stronger and became structurally defining. The quasi-classical narrative from the beginning had to disintegrate after the main character lost his ultra-empathy and began collecting and buying stories in some sort of pre-apocalyptic panic. Thus, from a certain moment onward the labyrinth gets the upper hand, the reader is forced into the labyrinth in place of the Minotaur himself. And as we know from Borges, the labyrinth can be located not only in space, but also in time.

Another hallmark of this novel is the way in which empathy—a word that appears often in the text—is the primary way that the book builds its relationship with the reader. The many lists and recursive moments make for what we might call, to borrow a term from nonfiction, a “disjunctive novel” with tangents built upon tangents. Yet it comes together as a portrait of a human life just as much as a story that follows a more traditional architecture. Can you talk about your writing process, and how you pulled this book together from so many disparate strings of story that don’t hew to the traditional Aristotelian three-act structure?

The truth is that I got lost many times. Building a labyrinth is no easy job; I now understand Daedalus. Perhaps sorrow and empathy through sorrow were the Ariadne’s thread that guided me, sometimes more intuitively than anything else. Gathering all of the stories and their tangents and corridors into a single whole was the hardest part of the writing process. It seems to me that there are certain mainstays, connecting threads, or as they are openly called in the novel “places to stop,” which lead the reader through the whole labyrinth. The repeated appearance of the basement in different variations, of the theme of the abandoned child and several other themes that constantly crop up try to maintain a certain wholeness.

The truth is that I got lost many times. Building a labyrinth is no easy job; I now understand Daedalus. Perhaps sorrow and empathy through sorrow were the Ariadne’s thread that guided me, sometimes more intuitively than anything else. Gathering all of the stories and their tangents and corridors into a single whole was the hardest part of the writing process. It seems to me that there are certain mainstays, connecting threads, or as they are openly called in the novel “places to stop,” which lead the reader through the whole labyrinth. The repeated appearance of the basement in different variations, of the theme of the abandoned child and several other themes that constantly crop up try to maintain a certain wholeness.

“Purebred genres don’t interest me much,” your narrator says, and that strikes me as something that you—who have worked in so many genres yourself—might also say. In Physics you sometimes write about the world and the species, which is unusual for something that calls itself a novel. It made me wonder whether you call this book a novel at all. If not, what do you call it? If so, what does that say about the capacities of the novel? Do you feel that the novel’s capacities are changing right now?

I don’t have a problem with calling it a novel. We can also think of it as a time capsule, a Noah’s arc that gathers animals of different genres and stories of all kinds, if we let ourselves play that game. The books that interest me are difficult to define in terms of genre. Such as A Thousand and One Nights, for example, or In Search of Lost Time by Proust, or Joyce’s Ulysses. But that doesn’t make them less important for the history of literature—on the contrary. I think that the novel today is facing new challenges and new borders. It arrives with urgency, alarmed, to tell about that which pure economics or pure science cannot. I have noticed that in certain bookstores, due to the title, they’ve put my novel in the hard sciences section. Which I actually find amusing. I’ve always thought that between, say, Linnaeus and Andersen, just as between Einstein and Joyce, there are a lot more commonalities than we might suspect.

There were times when Physics felt like an autobiography of Bulgaria—an exploration of its recent history seen through one set of eyes living through several lives. In particular, the WWII era and the fall of Communism felt inextricably bound. Do you see this as a particularly Bulgarian book?

Yes and no. On the one hand, this is a book that begins its narrative in “the saddest place on earth,” as the Economist called Bulgaria in 2010. The story about the boy during the late afternoons of the 1970s/80s is also typical for the eastern part of Europe during socialist times, and the everyday fears from that time can also be recognized geographically. But the sorrow of the Minotaur, for example, far and away outstrips and overtakes Bulgarian sorrows. And when the narrator himself starts on his path through the labyrinth of Europe, he realizes that melancholy has washed over the continent. The book is too personal to be nationally marked. The personal is beyond such markers. The sense of abandonment felt by the Minotaur, who is outside of time, is the same as that of the boy from the 1980s. Myth has made the tragedy of the one very poignant, but when you tell both stories in parallel, you’ll see that the tragedy in both cases is equally strong.

The translator for Physics, Angela Rodel, has been a major force behind the recent increase of Bulgarian literature on the English-speaking scene. How closely did you work with her on this translation, and what do you see as the challenges of translating this book in particular?

author photo by Vassil Tanev

Angela Rodel is indeed an excellent translator. By the way, she won an NEA grant to translate the novel. Our work together was both pleasant and intense. I like translators who have questions for the author and take advantage of the fact that he’s alive. I realize that my books are not easy to translate, because they depend a lot upon the language itself, the expression and phrasing, upon hesitation. Besides that, many different genres have been woven into them, such as the Socratic dialogue, explications of quantum physics, lists, the mythological text, as well as the Minotaur’s speech in hexameter. I think the hexameter was the hardest part for all the translators of the book. The translation of the title also turned out to be quite a challenge. Tuga (sorrow, melancholy) is not simply a word, but a concept and different languages interpret it quite differently. Is there a geography of sorrow, besides a physics? Can we talk about a migration of sorrows? Perhaps that is one of the challenges facing the various translation of the novel—to what extent our sorrow is translatable.

In 2009 [as participants at the Sozopol Fiction Seminars] we talked by the Black Sea, and I asked what you were working on. “Anything to keep me from writing a novel,” you replied. It looks like the novel managed to win that battle. Is that your typical relationship with novels? Are you avoiding another one right now?

Right at the moment I’m avoiding the beginning of a novel. It’s like hunting—even though I’ve never been a hunter. You shouldn’t get too close too quickly to the animal that is the novel. It shouldn’t get wind of your intentions, much less your scent. I simply aim to track it, to see where it will lead me. Unlike serious writers, I never have a clear idea of what my main character will do, where he’ll go and how everything will end. How could I know? I simply follow the tracks, trying not to lose them and quickly writing down my prey.