Richard Bausch is an exacting writer. With precise language that lends a breathtaking verisimilitude to his fiction, Bausch lays the groundwork in which settings and characters—their smallest actions and passing conversations—seem not only memorable, but inevitable. Immersed in his books, you see with new clarity.

I recently had the privilege of joining him in the Moss Workshop at the University of Memphis, a model he began more than sixteen years ago. Just in time, too. He has recently accepted a position with the faculty at Chapman University in California, a post he assumes in August.

Bausch is colorful, uncensored, and opinionated—unruly, even—like someone who would (and did) leave his car idling by railroad tracks to jump a passing train. He often wears a baseball cap pulled low over his brow, beneath which his eyes have a mischievous gleam. He’s willing, always, to try his hand at something new: the guitar, say, or stand-up comedy. He loves theater and film, often tossing out a quick quote or recounting a salient scene. Through eleven published novels and eight collections of short stories, Bausch has proven to be not only prolific but consistently excellent, a writer whose discipline equals his passion.

Bausch’s dexterity with short stories elevates the form. His straightforward, minimalistic style doesn’t pull shazaam endings, or plot pyrotechnics. But a story like the O’Henry-winning “What Feels Like the World” chokes me with emotion every time. Using simple, direct dialogue, Bausch fixes his stories’ terrain in the mind. It’s as if he turns your head and says “There. Now look.”

Interview

Emily Besh: Who ignited your desire to write, and when did you begin to identify yourself as a writer?

Richard Bausch: I had a teacher named Helen Garson when I was in my first year of college, who looked at me after reading something I’d written and said, “You’re a Southern writer by definition with all this family stuff in here, and you’re going to be a great one, I can tell.” I lived on that for a long time—through a lot of bad times. I ended up teaching with her for twenty years, and sending my own students to her. And she got a signed copy of every book as it came out, and with every one she wrote me a lovely letter, appreciating what she found in it. A great teacher.

Richard Bausch: I had a teacher named Helen Garson when I was in my first year of college, who looked at me after reading something I’d written and said, “You’re a Southern writer by definition with all this family stuff in here, and you’re going to be a great one, I can tell.” I lived on that for a long time—through a lot of bad times. I ended up teaching with her for twenty years, and sending my own students to her. And she got a signed copy of every book as it came out, and with every one she wrote me a lovely letter, appreciating what she found in it. A great teacher.

And there was another, Lorraine Brown, who one day when I said I didn’t think I had it in me to write one more scholarly paper, smiled at me and said, “All right then, write me a verse play, like Cuchulain’s Fight with the Sea.” That was the Yeats we were reading. She was another great one.

As to when I truly began to identify myself as a writer, it must have been when I sold the first novel. I remember going to the door and pushing it wide open and standing in it with my legs slightly apart, like a man expecting a high wind, and cupped my hands to the sides of my mouth and shouted “Listen up everybody! I’m a novelist!”

When I was a lot younger than that, I went around a lot with the suspicion that I might be a writer, afraid to think about it too directly, and feeling presumptuous and pretentious for the thought.

And of course the doubt is always heavy and never goes away, nor does the tentativeness about it ALL.

You give subtle attention to seemingly minor moments in your narratives. How often do you find yourself saying “too much,” rather than “not enough?”

I seldom question or edit much as I’m writing. During the process of thinking about it all and trying to revise and be sharp, I go back and forth, sometimes feeling it is too much (usually in this case it is more about showing off my own skill, or giving forth the best and most flattering sense of my tender soul and my ‘bag of sorrows,’ as Frederick Busch put it once—than contributing to the reader’s visceral feeling of the events I’m describing)—sometimes feeling it is too much, and sometimes feeling it is not enough, anemic because I’ve gone past it without looking at it coldly and as a stranger might. I want there to be enough for the reader to care what happens; and I want the words to disappear, in a way, so the reader is not so much aware that he is reading. It is indeed a fine line, but when you go through it 75 times, it gets a little clearer. You’re better able to tell the difference between the anemic or slipshod, and the self-indulgent or excessive for its own sake. Everything should be subservient to the story, including all my opinions and all my attitudes and all my ambitions, too.

You hit the literary world running—your first two novels published back-to-back. Could you tell us about that? With eleven novels and eight collections of short stories, it doesn’t seem like you’ve slowed down much.

It went like this: I sold my first novel, Real Presence, under the title, The Vineyard Keeper in early April of 1979. I was 33 years old, about to turn 34. James Dickey, having read the book, called me and suggested the title Real Presence. I didn’t like it at first, but can see now that it is the only possible title for that book. Later that summer, after experiencing the heady validation of selling the first one, and on the good advise of my pal Susan Richards Shreve, who already had two books out, I began a second novel.

It went like this: I sold my first novel, Real Presence, under the title, The Vineyard Keeper in early April of 1979. I was 33 years old, about to turn 34. James Dickey, having read the book, called me and suggested the title Real Presence. I didn’t like it at first, but can see now that it is the only possible title for that book. Later that summer, after experiencing the heady validation of selling the first one, and on the good advise of my pal Susan Richards Shreve, who already had two books out, I began a second novel.

I was calling that one I Don’t Care If I Never Get Back, because it began with a kid obsessed with baseball. I finished that one in early January, under the title Take Me Back. Just as I delivered that novel, news came in that Real Presence would be a Book of The Month Club Alternate Selection. And then in early June, after the book came out, it was reviewed in Time. Take Me Back was sold and in galleys before Real Presence appeared. And when in May a year later Take Me Back came out, Jane Smiley said to a mutual friend, “Maybe he’s dying, and trying to get them all out before it happens.” That’s Jane’s humor, and I laughed when I heard it.

Anyway, because the second one came so quickly, I got it into my head that I had it figured out now, and would be delivering a novel roughly every four months. Take Me Back got nominated for the PEN/Faulkner award, with a citation written by Walker Percy. I got to know him at the awards ceremony. And pretty soon I was walking around trying to write a philosophical novel a la Mr. Percy, and it was my wife, Karen, who finally called me on it, after two years of misery and four different manuscripts that I never let out of the house.

Now I don’t know what the average is, and am not inclined to use the math necessary to figure it. I do know that I have never gone longer than three years without publishing a book since 1980. And if I can finish the present novel and deliver it and have it accepted, I will publish it in 2013, probably, which keeps to the never-more-than three years pattern.

How does the germ of a story begin? Does the process still surprise you?

They come in different ways and with different matters trailing along in them. I carried “What Feels Like The World” around—the floor of it: a man and his overweight daughter, and the sorrow parents feel watching their children go into a building where they can have no immediate effect on what happens to them in there—I carried that around for a year or so, because each day for a long while I’d seen this heavy man with his overweight daughter walking up to the door of my kids’ school. There was a special bond between them. And then carrying that around as I was, that image and that sense of the helpless love I knew he felt in the circumstance, his heavy darling walking up to the door and in, where, children being as they are, she would suffer all that they both knew she would suffer the whole day long, and it was in their faces, too.

Carrying that around as I was, I happened to be at a gymnastics demonstration at that very school, where about nine of the seventy kids ran around the vaulting horse instead of going over it. (I think the heavy girl was in an earlier class, or was absent.) But of course there were other heavy kids and watching them go around the vaulting horse, I had an image of this man, this father of the heavy girl throwing a fit in the hallway of the school about his child, saying “What the hell. Everybody can do SOMETHING, can’t they? Why put her through this humiliation?” I had that picture of him shouting down the hallway of the school, and I knew then that I would write the story. Or, a story. Something to do with that helpless feeling the parent suffers when his child has to go through the badness of that kind of situation.

When I got to the end, I read the last paragraphs to my wife, who said, “You can’t leave it there.” I read the end to some friends, all of whom said, “No, you can’t leave it there. The reader will want to know.”

So I tried like hell to render the rest of the scene, and I did it both ways. [The first], where I wrote her sailing over the vaulting horse, felt like cheating, like treacley television Hollywood cotton candy reality existing only to pander to the already asleep. The second way, where she failed to get over, felt like cheating it another way, rubbing a smart reader’s nose in it purely for the self-indulgent pleasure I could get out of what I could do with English sentences to make him squirm and hurt past the experience. So I left the end as it was and sold it to The Atlantic a couple of weeks later. And it won an O. Henry Award and I still get people who want to know if she gets over that vaulting horse.

It was after it had been in the magazine, and sometime just before it appeared in my first book of stories, that I was visiting a class my friend the poet Roland Flint was teaching and he pointed out what the story was really about: “It is soaked in grief,” he said. “And of course grief, the thing you can’t get over, is that vaulting horse.” I did not know this in the writing of it and this is why I talk so much about trying to let go of what you think and just feel your way through it like a child making that drawing, seeing it directly and without attitudes or opinions or, really, beliefs, either.

I never sketch out any plot, and will only make a note as to the next minute or so in the life of a character or some idea of where he/she’ll go in the next couple of pages, if I have some sense that I won’t be able to call it up when I sit down again. If the story does not surprise me, I do not trust it, and will usually not let it go until it does surprise me. The surprises are all the fun of it. And if you trust them enough you’ll write a lot of stuff that will please you every time you look at it for the surprises it gave you. Somehow they always stay fresh.

When you return to a scene, how do you go about adding to depth and texture?

There is a simple answer to this one, though it is difficult as hell in practice. In re-writing, along with paying attention to the writing, the sentences line by line, I also try to see if I am involving all the senses, how it feels on the skin, texture, smells, sounds, sight. All of it. And then in looking at what is said I try to make sure that every line of dialogue is doing more than one thing. That is, carrying the story forward, giving character, leaking in history and the matters that are at issue, the what’s-wrong, as it were, but keeping all this artifice from being visible to the reader. Then having worked all that, and gone over and over it, I go over it still again, looking at the writing again, the words and lines. I want all the artifice to disappear; I want everything to disappear except these people in their trouble, whatever it is. And it is always some kind of trouble because that is the province of the human story, and news of the spirit in narrative can only arrive through the abrasions of conflict. Conflict, which scrapes the barnacles from the soul and lays it bare.

What do you grow against? The classics?

Oh, yes, of course the classics—and books, books, books, all the time. Right now I’m reading Tolstoy—War And Peace for the fifth time, Anna Karenina, for the third; Kawabata—Thousand Cranes; Shakespeare—over these last five months, King Lear six or seven times, listening and reading; Romeo and Juliet four times, listening and reading; As You Like It twice, Macbeth three or four times; Hamlet four or five times; Twelfth Night and Julius Caesar; Graham Greene—The Power And The Glory for the third time; Eudora Welty—Delta Wedding; Percival Everett – Assumption; Alix Ohlin—Signs And Wonders; Trollope—The Eustace Diamonds for the first time (and I’ve been reading it for a year); and Philip Roth—Indignation, and I just finished Nemesis and Everyman.

In the workshop you once said it would be a “sin” for us not to write. Could you elaborate?

We live in a culture that sees trying to write as some sort of indulgence of the ego, when not a plain presumption. But if you have talent for it, you are morally obligated to do it, and all one need do is look at that passage in the Bible about the ten talents: it’s where we get the word. The very word implies responsibility.

I had a dear friend, gone now, the poet Roland Flint, who called me one night crying, because he’d had this thing happen on his way home from school: he saw a little toddler on the island between two lanes of traffic. Stopped to keep him from wandering into the road. Held his hand and walked him across the street, thinking all the while about his son, Ethan, who was run over by a car and killed before his eyes twelve years earlier. The toddler’s parents came running from a house in the opposite direction of where Roland was walking the child, and the father got down on one knee and yelled at the child. “Don’t EVER go out of the house without Mommy and Daddy.” And Roland had to say, “I think he’s very frightened now.” And the parents stood there, the mother holding the child, now, and Roland went on to say, “I must tell you, I lost my son in this way, twelve years ago.” The parents said they were sorry and went on to their house and in, and Roland went, crying, back to his car, got in, drove home, wrote about the event in his journal, then wrote a poem about it, still crying, and finally called me.

wandering into the road. Held his hand and walked him across the street, thinking all the while about his son, Ethan, who was run over by a car and killed before his eyes twelve years earlier. The toddler’s parents came running from a house in the opposite direction of where Roland was walking the child, and the father got down on one knee and yelled at the child. “Don’t EVER go out of the house without Mommy and Daddy.” And Roland had to say, “I think he’s very frightened now.” And the parents stood there, the mother holding the child, now, and Roland went on to say, “I must tell you, I lost my son in this way, twelve years ago.” The parents said they were sorry and went on to their house and in, and Roland went, crying, back to his car, got in, drove home, wrote about the event in his journal, then wrote a poem about it, still crying, and finally called me.

He said, “To think that I could cheapen Ethan’s death by writing a goddamned poem about it. To think that I could use it in that way.” And I listened, and told him I loved him and understood, and we hung up. But then I thought about it and I called him back. “Roland, you’re supposed to write the poem. You’re morally obligated to do it. You must do it. For Ethan, and for all those people out there who don’t have the words, who’ve gone through this very thing. It’s what you’re absolutely supposed to do now.”

And he wrote his poem, “Stubborn.” And had it printed in a large picture frame, and inscribed it to me like this: “I wondered who I’d sign this first copy to, but of course should have known all along it would have to go to the Bausch who made me write it.”

It was one of my proudest possessions for all the years I was in that house in Virginia, and as far as I know, it is still on the wall there.

But that’s what it really means: the ten talents and us, who have this talent.

Further Links & Resources

- Follow Richard Bausch’s Ten Commandments for writers.

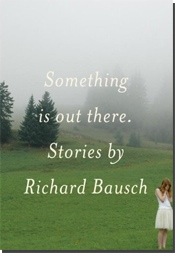

- Get Baush’s latest book, the collection Something Is Out There. [Amazon. Powell’s. Indiebound.]

- Read Roland Flint’s poem “Stubborn” (scroll down to the second poem on the page).