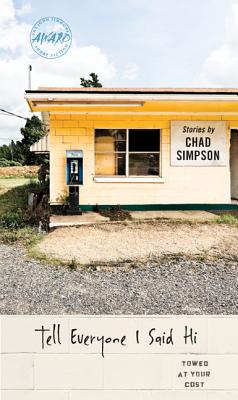

In Tell Everyone I Said Hi, winner of the 2012 John Simmons Short Fiction Award from The University of Iowa Press, Chad Simpson mines his native Midwest for tales of heartbreak and longing. The eighteen stories that comprise the collection, “roam the small-town playgrounds, blue-collar neighborhoods, and rural highways of Illinois, Indiana, and Kentucky to find people who’ve lost someone or something they love and have not yet found ways to move forward.”

In Tell Everyone I Said Hi, winner of the 2012 John Simmons Short Fiction Award from The University of Iowa Press, Chad Simpson mines his native Midwest for tales of heartbreak and longing. The eighteen stories that comprise the collection, “roam the small-town playgrounds, blue-collar neighborhoods, and rural highways of Illinois, Indiana, and Kentucky to find people who’ve lost someone or something they love and have not yet found ways to move forward.”

I first met Chad five years ago at The Sewanee Writers’ Conference where he was a Tennessee Williams Scholar in Fiction. I like to think we both instantly recognized a kindred spirit and since then we’ve maintained a friendship via email, phone, and the time-honored tradition of sipping bourbon at AWP hotel bars. He’s a good friend, a trusted reader, and I don’t think I’ve ever met anyone more universally likeable. And that’s all fine and well as I often preach at my own students the importance of being “a good literary citizen.” In many ways his generosity and kind soul probably play into his work as you can’t write a character the way he does without truly caring for them.

But there’s also something else: a staggering talent, an empathy and understanding of the human condition that leap from the page. Those things don’t hurt either.

One of the aspects I admire most about Chad’s stories is their unassuming beauty. Like the quiet girl at the end of the bar who looks up from her drink and brushes the hair from her face, only to reveal something so lovely and incredibly true you didn’t even know it could exist. This is the feeling I get while reading Tell Everyone I Said Hi. Chad’s stories amaze me. They do now and they did when I first had the privilege of reading them, half a decade ago in a shared workshop somewhere in the mountains of Tennessee.

Interview

Eugene Cross: Author Jim Shepard, judge of this year’s Iowa Short Fiction Award, who selected Tell Everyone I Said Hi as one of two winning manuscripts, describes you as writing “with a piercing tenderness and sadness about loss and helplessness and the impossible decisions we face every day…” And indeed, your characters face loss of all kinds, whether it be the death of Peloma’s mother and Clem’s wife, Marcella, in the story sequence “Peloma” and “Consent,” or the seeming loss of a moment and a good intention, as in the shorter “Let x.” What role do you feel loss and your handling of it plays in your work?

Chad Simpson: You know, it’s strange to me when I hear from people about how much loss and loneliness they see in these stories. I don’t think I’m really ever setting out to write about such things. When I’m working on a story, I’m usually trying to get at an image, or some moment in time, that I want to make meaningful, and as I begin to do that, I start thinking about things like tone, and character, and scene and setting, etc. Then, as I’m making sentences, it seems loss finds its way into them in one way or another.

I did, however, think quite a bit about loss and loneliness as I arranged the stories in the collection. I’ve published about fifty stories over the past ten years; when I was selecting stories to include in Tell Everyone I Said Hi, I considered not just which ones “fit” thematically—because, really, most of them would—but also how the stories handled the themes of loss and loneliness differently, so that I could present variations on those themes over the course of the eighteen stories in the book.

You have been described as a Midwestern writer and the places and people of that landscape certainly populate your stories to amazing effect. Do you embrace this label? And if so, what makes you continue to explore that landscape?

I definitely embrace being a Midwestern writer. Many of my favorite short story writers have spent a lot of time exploring this particular landscape, too—Stuart Dybek, Charles Baxter, Bonnie Jo Campbell, Dan Chaon.

I continue to explore the Midwest and the people that populate it because of its beauty, its ugliness. Because of all the yearning I find here.

I also have a little bit of a political motive, in that I sometimes dislike the way Midwesterners are portrayed in fiction and film. Dan Chaon said something eloquent about this a while ago in an interview I read online that very much captured how I feel about it, but I can’t find the interview. The gist of what he had to say, if I remember it correctly, was that the Midwest is often portrayed as a “simple” place filled with “simple” people. It’s the place people want to flee, and return to only very reluctantly during holidays, only to be reminded all over again of why they left in the first place. There are certainly aspects of the Midwest that I dislike, that I hate, but there’s also a lot to love here. And this place’s people are no less complex than the people living anywhere else in the world. It’s my hope that my stories occasionally get at the complexity of this place and the lives of its inhabitants, that they embrace this place’s contradictions and ambiguities.

One of the things I admired most about Tell Everyone I Said Hi was the ease with which you navigate story length. I was never jarred while switching from flash fiction to longer pieces, at least not in an unsatisfactory way. In fact, some of the shorter pieces such as “Miracle,” “House Calls,” and “fourteen,” are among my favorites in the collection. When do you typically realize if you’re working on a longer or a shorter piece and did you face any particular challenges when deciding how to sequence them in the manuscript?

I used to think I had a good idea about how long a story was going to end up being when I sat down to write it. For a while, my estimates were pretty accurate. Over time, though, I’ve become more and more surprised by the writing process. Stories that reach twelve pages eventually get reduced to three. Stories that begin as sketches, vignettes, wind up at 5000 words. I don’t think I realize that I’m working on a longer or shorter piece so much as I try to figure out what’s going on in the story, and what I need to do in order to convey that thing as effectively as possible.

I tried when sequencing the stories to create rhythms, beats. I like the idea of each story standing on its own and doing its thing, but I realize that once a story is put inside a book along with other stories, readers will most likely hop from one to the next, just keep on reading. To this end, in addition to trying to create certain rhythms as the stories progress, I also sequenced them in such a way that there are little echoes from one story to the next. For instance: “Miracle,” the first story in the book, involves two brothers; it is followed by “You Would’ve Counted Yourself Lucky,” which is also a story about a pair of siblings. I’m not sure I faced challenges about sequencing so much as I tried to find a way that the stories together might resonate more fully than they would on their own.

Your portrayal of adolescents can be rather dark. Whether it be Peloma’s half-hearted suicide attempts or the unabashedly sexual nature of a story like “fourteen” you don’t shy away from the more disturbing aspects of youth. What drives this?

Your portrayal of adolescents can be rather dark. Whether it be Peloma’s half-hearted suicide attempts or the unabashedly sexual nature of a story like “fourteen” you don’t shy away from the more disturbing aspects of youth. What drives this?

About seven years ago, I saw Tim O’Brien give a reading, and he said something that really stuck with me about childhood crushes, something about how we tend to denigrate the love children feel for one another, how we call it “puppy love” and treat it as if it’s not the same as the love adults feel. O’Brien asserted that he believed the love we feel for someone else at five or six years old isn’t really all that different than the love we feel for someone fifty years down the road.

To my mind, children and teenagers are just as emotionally complex as adults, and so when I’m writing them, I do my best to embrace their complexities, disturbing bits and all, which is pretty much the same thing I’m doing when I write adults.

You’ve published widely both in print and online, and you have an epic online presence. You and I have had conversations about writers we’ve corresponded with and never met, and how those “cyber-friendships” are very valuable to us as writers. Could you speak to their importance to you, not only now, but as a beginning writer?

Well, first: I don’t think of my online presence as being very epic. I have a website and an author page on Facebook, but my wife, Jane, is responsible for getting those things going. I also post things on twitter sometimes, but if I’m not promoting something and am instead trying to be funny, I’m usually stealing what I’m saying from or attributing it to Jane.

That said, I’ve certainly valued relationships I’ve had with writers I’ve met online over the years. I’ll say this, though, too: I was late to the online lit community. I was in grad school from 2002-2005, which would have been a pretty good time to find like-minded people online, but I was mostly reading print journals then and talking to my writing friends in person, at bars or in the grad student offices. It wasn’t until I began adjuncting at two different colleges my first year out of grad school that I began really reading online literary magazines and visiting the websites of certain writers whose work I liked. I was pressed for time, always prepping for class, and when I found a moment or two to relax, I would read some stories online, where I found a lot of really great work, especially flash fiction and short-shorts. I’d been writing almost exclusively longer stories in grad school, but I began experimenting with form then, working on flashes and shorts, and then submitting them to online magazines whose work I liked. I also started my first blog around that same time and linked up with some other people who were working jobs and trying to get some writing done.

It took a little while, but I eventually began corresponding and sharing work with some really great writers, many of whom have now published books and have teaching jobs. I think these relationships were especially important to me because of where I was/am living. It’s not always easy in small towns in the Midwest to find people who’ve been reading William H. Gass or trying to write stories in fewer than 750 words, even when you’re working in an academic setting, and especially when you’re new to it and you and everyone else is so busy. It certainly meant a lot to me to find some of these writers online. And I love how easy it is to reach out to someone after you’ve read something of theirs to tell them they just slayed you. And I love when people reach out to me in this same way, too. Most of the time, I don’t mind the solitude of this work, but it’s nice every now and then to discover your words have actually made an impact on someone.

In addition to being the title of one of the stories, can you tell me a little bit about how Tell Everyone I Said Hi applies to the collection as a whole?

In addition to being the title of one of the stories, can you tell me a little bit about how Tell Everyone I Said Hi applies to the collection as a whole?

There isn’t a lot of direct conflict in these stories. I love that bit of advice Charles Baxter gives in “Creating a Scene” from The Art of Subtext about having your characters make a scene, about how having your characters act out can do a lot to actually “make” a scene in fiction. That said, my characters rarely make such scenes. There are small and quick moments of direct conflict in the stories in this collection, but much of the tension in the pieces comes from something else—typically a kind of disconnect. There are rifts large and small separating these characters from one another—rifts of geography, perspective, potential understanding, etc.

There’s also a lot of yearning in these stories.

There’s a lot of isolation, a lot of dislocation. A lot of loneliness.

It’s my hope that the title—Tell Everyone I Said Hi—manages to evoke some of these things.

Knox College, where you’re a member of the faculty, gave you a Distinguished Teaching Award in 2010. Can you speak about how you balance the two, teaching and writing, and perhaps how they affect each other? Can you speak a little, too, about the jobs you held before you became a teacher and writer?

I spent four years working various jobs before I applied to grad school, and I can’t overstate how important these years were to me as a writer. There were the jobs: I repaired broken pallets at a pig slaughterhouse; worked as a security guard at Walmart and Boeing; did a year of AmeriCorps, during which time I helped out at a homeless shelter and a Boys & Girls Club; and spent two years as a juvenile probation officer. But more than that, I needed the time. I came to writing late, at the age of eighteen, really, and I needed to play catch-up. I read and wrote a ton over the course of those four years. I didn’t put in all of my 10,000 hours, but I put in a few thousand, for sure.

The time I spent working “real” jobs came in handy, as well, once I began grad school. It was a lot easier to stay in the chair and write for four or five hours at a time after I’d worked in a juvenile detention center, where I was locked up with the kids for eight hours a night. It also helped because I was hungry—I very much wanted to be around people who valued reading and writing, and I wanted to figure out how to put a story together, learn the various ways in which I was failing at it on my own.

The best thing about being a teacher is that I remain surrounded by people who value reading and writing. I work with roughly 100 students each year who approach fiction writing with all of these amazing ideas about how stories work. They share work with me that is raw and beautiful and means everything in the world to them. They are a continuous source of inspiration for me.

Sometimes I don’t find as much time to write when I’m teaching as I might if I were still working eight-hour shifts at Walmart or the detention center, especially when I wake up thinking about some problem a student encountered with a story and how she might fix it, instead of thinking about my own work, but all said, I think it’s a pretty decent trade-off. Typically, the more I give to my students, the more I get back when I sit down to write, and the more I give to my writing, the more I end up having to offer to my students.

Links & Resources

Listen to Simpson read his story “Translated from the French” at Better.

Go to Tell Everyone I Said Hi readings and events.

Read “The Woodlands” from Tell Everyone I Said Hi at American Short Fiction.