On a freezing winter night, a teenager sneaks out to her first party, her pet rat in her pocket. Uncertain about the stability of their newly open relationship, and navigating a tangle of emotions about their upcoming top surgery, a writer negotiates the vertigo of dating during COVID. A non-binary office worker struggles to articulate their identity while shepherding their nephew through a convention for trans YouTubers. Unable to explain why dressing as a mother pioneer for a school reenactment of the Oregon Trail ignites such intense dread, a young child instead dresses as an ox and embarks on a revelatory journey.

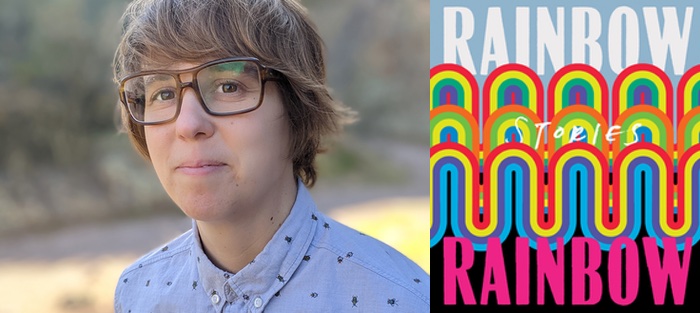

These are just a few of the arresting, utterly specific characters in Lydia Conklin’s debut story collection, Rainbow Rainbow (Catapult), which hits the shelves May 31. Devastating, tender, and hilarious by turns, Rainbow Rainbow explores the vulnerable rites of passage that help us understand who we are and who we need to become. Lydia and I spoke via email.

Interview:

Emily Nagin: There’s this convention in contemporary fiction of a “universal now,” a sort of hazy present day that feels contemporary but could be any time within a twenty-ish year span. In contrast, your stories feel very rooted in time and place, whether that’s late ‘90s suburbia or a college town in the immediate aftermath of Trump’s election. What made you decide to eschew that device and make your timing so specific?

Lydia Conklin: Being a teenager in a time when, even in a “liberal” town, queerness was very much not okay and drew so much violence and hate, versus existing now in the grand year of 2022, when, while things are of course in no way perfect still, a shocking amount of progress has been made in queer and trans issues, I’m very aware of the nuance of how quickly queer history can change under your feet. Because of that shifting political and cultural landscape, the stories have to take place at very precise moments. How me and my community was feeling about queerness and transness in the year 1999 was starkly different, but maybe no more bleak in certain ways, than in the moments following Trump’s election, etc. How the characters are functioning in the very different landscapes I’ve lived through since I started wrestling with gender and sexuality is at the heart of the stories.

That is very true! In a similar vein, “Pink Knives” is set during lockdown. What was your approach to writing about COVID and what are your thoughts on the way this particular moment in time might influence the way we write going forward?

I was nervous about writing about COVID, because it seemed like a lot of people were also writing about COVID at the same time. I think one challenge of writing about COVID is that large numbers of people were and are dealing with similar challenges all at once—and thinking very deeply and intensely about those experiences—so it felt hard to find a way to illuminate them in a way that thousands of other people hadn’t already thought about them. Obviously, people had an enormous variety of experiences within those broader challenges, but still, some of the main terrors and struggles were similar.

I was nervous about writing about COVID, because it seemed like a lot of people were also writing about COVID at the same time. I think one challenge of writing about COVID is that large numbers of people were and are dealing with similar challenges all at once—and thinking very deeply and intensely about those experiences—so it felt hard to find a way to illuminate them in a way that thousands of other people hadn’t already thought about them. Obviously, people had an enormous variety of experiences within those broader challenges, but still, some of the main terrors and struggles were similar.

I also imagined that people wouldn’t want to read about the dreary situation they were suffering through. I focused “Pink Knives” on two other larger emotional challenges that weren’t as common but were made stranger and more dangerous due to the pandemic—navigating the beginning of an open relationship and preparing for top surgery—and backgrounded the COIVD elements, to make the experience feel more particular.

In terms of how COVID may change how we write, I’m curious. I feel like the best writing about COVID may happen some time after it’s over, or sometime after this period of it is over, the way that seems to happen with wars. Maybe with reflection, peoples’ experiences will diverge even more and, with time, people will be ready to read about it? I don’t know, that’s just a theory.

The structure of a lot of these stories is really interesting in that many of them end right at the climax or point of greatest tension—there’s no real falling action or resolution. Can you talk about that narrative strategy?

I never really thought about it like that! But it is true that sometimes the most extreme action happens close to the end. A couple of times the story shoots ahead in time before the very end to give the reader some sense of what happened. But I also feel that in the stories you’re referring to, for me the climax is really the emotional moment of decision which occurs previous to the dramatic action, and then leads the character to take that action, though I can see how the climax could also be considered the action itself! I’m thinking of “Laramie Time” and “Counselor of My Heart,” for example.

There was also one story, “The Black Winter of New England,” where I struggled for years with the ending. I knew it wasn’t right, and I kept getting notes from literary journals saying they liked it except for the ending. I rewrote it and tried to fix it time and time again. Finally, I got it published at a dream journal, where we worked on the ending even more. But it still didn’t feel right. Then, when I started working with Leigh Newman at Catapult, she returned the manuscript to me with all her edits and one of her notes was that I would see that she’d cut the last four or so pages of “The Black Winter.” I couldn’t believe it! She just cut out the material I’d been fighting for a decade, and it worked. I wished I had met her years earlier. So that was an instance where I was dragging things out past the climax in a way that wasn’t productive.

That revision experience is so relatable! I can’t think of a single writer who doesn’t have at least one story with an ending they just can’t figure out. Sometimes they never click and sometimes, as in your case, they finally do, and it’s like magic. How do you stick with a story like that, one you know is good but that you have to keep revising over and over? How do you keep the faith?

It can be so hard to keep the faith. For me the problem is what a friend of mine calls snowblindness. After a long time working on a story, I can’t even see anymore what’s going on and am lost about how to fix it. I usually don’t have trouble staying emotionally engaged, because I try to seed my stories with some deep bit of emotion that can keep me caring on that level, but it gets hard to get under the surface or even to know what’s wrong. So what I do is, if a story isn’t coming together or I feel frustrated, I put it away for a long time—sometimes years. At that point I feel a little objectivity and I’m able to see it from a distance and gather the bravery to try the radical types of solutions that are often necessary at that stage.

This next question is also “Black Winter” adjacent, since that story focuses on teenagers. Often younger characters get flattened out in fiction, but you write them with such compassion and complexity—they feel very true to life. Can you talk about how you approach writing younger people?

I think a lot of times adults don’t give enough credit to how much they understood as kids—how in tune they were to the world around them. Kids, even very young kids, understand a lot, feel complex pain, are smarter and sharper and more observant than we may remember. They also have very dark complex layers. I try to access all those levels when writing kids—what’s funny about them, what they are confused about, how the dark shapes of the world are beginning to knit together for them. I try to put myself back in that place and remember how I felt and how I thought and all I was aware of, and the different moral codes I operated under. It’s such a weird time of life. I somehow feel like I still have access to it, which I feel lucky about.

I can’t really ask about the teenage characters without also tackling the adults around them, particularly Lisa Parsons, an older woman who shows up in “Ooh the Suburbs.” Lisa’s behavior toward the teenage characters, Heidi and Kim, is deeply inappropriate, but Heidi doesn’t have the experience to recognize that. As a result, Lisa ends up being this complicated character who you see from both the teenage lens and your own adult perspective. I was angry at Lisa, and simultaneously, I could see why Heidi was drawn to her. As a writer, how do you walk that line between empathy and accountability where your characters are concerned?

I think that’s a really difficult line. In fiction, I feel that characters who behave badly or act in ways the reader or writer would never act are fascinating to watch. Why would we want to watch someone do the dreary and good things we do every day? Of course there’s comfort and coziness in that, but it’s exciting to see a character behave badly or immorally. But then a character wouldn’t be interesting or real if you didn’t show their humanity, too. I think so long as the moral framework of the story is such that the immoral actions aren’t being promoted or excused, there’s still room for humanity for any character. But Lisa is a tricky one, and one I struggled with for years. That story was actually rejected eighty times before it was accepted by The Paris Review! It’s the story in the book I wrestled with the most.

I think that’s a really difficult line. In fiction, I feel that characters who behave badly or act in ways the reader or writer would never act are fascinating to watch. Why would we want to watch someone do the dreary and good things we do every day? Of course there’s comfort and coziness in that, but it’s exciting to see a character behave badly or immorally. But then a character wouldn’t be interesting or real if you didn’t show their humanity, too. I think so long as the moral framework of the story is such that the immoral actions aren’t being promoted or excused, there’s still room for humanity for any character. But Lisa is a tricky one, and one I struggled with for years. That story was actually rejected eighty times before it was accepted by The Paris Review! It’s the story in the book I wrestled with the most.

Yes! Sometimes the stories or characters you wrestle with the most are the ones that end up being the most interesting. Were there any other characters in the collection who challenged or surprised you?

Yes, I really struggled writing Asher in “Cheerful Until Next Time.” He holds some seriously problematic views and ways of looking at the world and some of his actions/reactions are ones that are alien to me, and pretty dicey morally. I was able to access him because in some other, different, yet fundamental ways, like in his gender identity and expression and the intensity of how he loves, I do identify with him deeply.

Sometimes when I’m writing a character who is very different from me and is making decisions I would never make, I think about what person in my life would adhere most closely to that character’s decision-making, and try to put myself in that person’s shoes. Also, by the end of a process with a story, I feel like I know a character well enough to predict what they would do in a given situation, even if their decisions are very different from ones I would make.

A lot of your characters are in a liminal space, whether because they’re children, or in the early stages of rearticulating how they understand and present gender, or living in a new place (or some combination of these). What about these in-between periods captures you as a writer?

I think that’s because I struggle with transitions! Haha, of all kinds. Which is difficult because my life has been full of them. For one thing, I’ve moved nine times in the last twelve years. Being in a new place, despite all its difficulty and stress, has a brightening effect on my life—it allows me to see everything in a new way and to write at my best. I like writing characters who are in those vulnerable, intense moments, whether it’s at the end or the beginning of a new relationship, arrival in a new city, the beginning of sobriety, or on the eve of or just post a gender transition.

Writing any book is a learning process in terms of both research and craft. What’s the most useful thing you learned while writing Rainbow, Rainbow?

I realized when I started to assemble the stories for my collection that some of them were me taking a stab at the same material over and over—like I had three or four versions of “The Black Winter of New England” that I thought were different stories. They were fine existing separately, but they couldn’t all sit in a collection together. I had to pick the best of each story cluster, so I had a lot fewer stories than I thought I had (though still a deranged number of stories). I don’t think I could’ve done anything differently; it took many stabs to circle around the material and get it right. But that was something I noticed about my process that I hadn’t known before assembling the collection.

Okay, last question, the one I always ask—Pick any character and tell me:

When asked, which song do they tell people is their favorite?

What’s the song they love but would never admit to loving?

Ooh this is such a good question! It reminds me of my friend who, as a goth teen, used to ride the bus with “Always on my Mind” by Willie Nelson blaring in his earphones. He realizes now everyone could’ve heard it and was probably laughing at this sour, tough boy listening to such a sappy song. I’ll pick Melissa from “The Black Winter of New England.” She’d tell people her favorite song was “Stinkfist,” by Tool, but she really loves the cover of “The Man Who Sold the World,” by Nirvana.