It’s Holy Week and Amadeo Padilla is ready to be reborn. Under the mentorship of the stern Tío Tíve, Amadeo will play Jesus in his New Mexico town’s Good Friday procession, a grueling role requiring him to be crucified while his friends and neighbors look on. Amadeo is convinced that this painful rite of passage, granted only to a privileged few, will lead to both personal and spiritual renewal.

Then Amadeo’s fifteen-year-old daughter Angel arrives on his doorstep, a reminder of the past for which Amadeo wishes to be redeemed. Hugely pregnant and fleeing her own mother’s house, Angel announces that she has come to stay with Amadeo and his mother, Yolanda, until her baby is born. But Yolanda, the family’s fulcrum, is uncharacteristically absent, struggling with a terrible secret that she fears will rip her family apart.

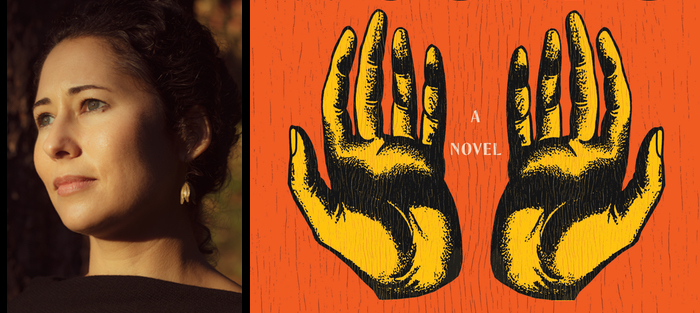

Surprising, compelling, and full of complicated warmth, Kirstin Valdez Quade’s novel The Five Wounds (W.W. Norton) is the kind of book that sticks with you long after you put it down. We spoke via email.

Interview:

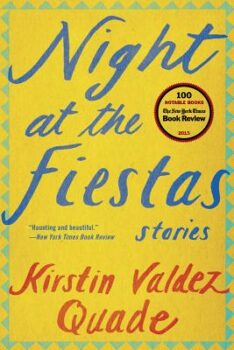

Emily Nagin: I was a big fan of your story collection, Night at the Fiestas (W.W. Norton, 2015), which includes a shorter version of The Five Wounds. Can you talk a bit about why you chose this story to expand into something larger? What about it told you it could be a bigger project?

Kirstin Valdez Quade: That’s really kind—thank you! When I finished the story “The Five Wounds,” I felt done with it, and moved onto other stories. After it was first published, my now-editor asked if I’d ever considered extending it into a novel, a suggestion that I declined pretty swiftly. I was working on my collection and was pretty committed to short stories. But two years after it came out, as I was looking through some new half-formed story drafts, deciding what to work on next, I suddenly saw that three of them dealt with essentially the same family dynamics that were in “The Five Wounds.” When I recognized versions of Amadeo, Angel, and Yolanda, I realized that I actually still did have more questions about the characters. One major question was, “What happens the next day? Is Amadeo’s epiphany [at the end of the short story] really enough to make him change?”

Kirstin Valdez Quade: That’s really kind—thank you! When I finished the story “The Five Wounds,” I felt done with it, and moved onto other stories. After it was first published, my now-editor asked if I’d ever considered extending it into a novel, a suggestion that I declined pretty swiftly. I was working on my collection and was pretty committed to short stories. But two years after it came out, as I was looking through some new half-formed story drafts, deciding what to work on next, I suddenly saw that three of them dealt with essentially the same family dynamics that were in “The Five Wounds.” When I recognized versions of Amadeo, Angel, and Yolanda, I realized that I actually still did have more questions about the characters. One major question was, “What happens the next day? Is Amadeo’s epiphany [at the end of the short story] really enough to make him change?”

I decided to spend that summer writing my way beyond the last page of the story to find out if there might be a novel there. By the end of the summer, I was only more curious about where the characters were headed.

What was the process of growing a short story into a novel like for you?

I really enjoyed exploring Angel and Yolanda’s points of view and discovering who they are. Almost as soon as I started writing in their perspectives, they sprang into being and challenged the versions of themselves I’d known only through Amadeo’s eyes.

The trickiest part for a while was allowing myself to not feel beholden to the original short story. Because “The Five Wounds” had been published in The New Yorker and in an anthology and in my collection and was available online, it took on a kind of permanence. It took a long time for me to realize that I was allowed to break it open and take what was useful for the novel and leave behind the rest. The character Manuel was important for the story, but ended up not being a part of the novel, and some of the central action in the story never happens in the novel.

Now I think of the story and the novel as related but parallel possibilities for these characters. Even the characters themselves feel different to me in the two versions.

I love it when characters surprise you as they grow. Could you talk a little bit more about how Angel and Yolanda changed and challenged your initial ideas about who they were?

In the story, Yolanda exists only in a couple mentions; we learn early on that she’s gone to Las Vegas with her boyfriend, which means Amadeo is on his own when his daughter shows up unannounced. Without his mother to step in to take charge for him, he has to be the adult and answer to Angel’s needs.

Angel is present on the page in the story, but we only know her through her father’s eyes. My sense of who she was really developed as I spent time in her perspective. Her character was much flintier in the story—but as soon as I began writing from her point of view in the novel, I discovered her vulnerabilities, and also how observant she is. Her situation is pretty precarious, and, like so many kids in precarious positions, she has to pay attention—her survival depends on it.

While we’re on the topic of characters, although the narration is mainly owned by Amadeo, Angel, and Yolanda, characters like Angel’s teacher, Brianna, also get to speak. How did you choose your narrating characters? Did anyone’s voice not make the cut? For example, does Angel’s friend Lizette have a secret B-side?

Brianna is an outsider—she’s outside the family, obviously, but she’s also new to the community. I thought her point of view was important to open the novel up more. I worried that if the story only unfolded within the tight circle of the family, that it might become claustrophobic. Brianna’s role in the novel is similar to her role in Angel’s life—she offers Angel a glimpse of a larger world outside the community where she’s spent her whole life and gives her a sense of possibility.

There’s no secret Lizette B-side, but there is a Tío Tíve B-side! He had a whole arc of his own—even a romance!—and there was a lot that I liked about his story, but it wasn’t, in the end, as essential to the novel.

I would definitely read a Tío Tíve B-Side! I’m always interested in the pieces that didn’t end up in a novel. Inevitably, so much of what we write ends up on the cutting room floor, even things we really like, because as you said, they ultimately don’t serve the story as a whole. How do you decide what makes something essential to a story?

I was pretty fond of some of the material from Tío Tíve’s point of view—the storyline explored his marriage and his fraught relationship with his son, and his pain over his son’s addiction. Tíve has another perspective on the family dynamics, and his story offers more insight into the family history.

This was all interesting to me, but when it became obvious to me that I could pretty much lift out Tíve’s storyline without having to change much in the rest of the book, I knew I couldn’t keep the material. The other points of view were all tightly intertwined—when one of the characters acted, it affected the other characters. Yolanda’s secret has profound consequences for her son and granddaughter; Amadeo’s romance throws Angel’s world into disarray; Amadeo’s failure with his first windshield repair job threatens his mother’s career. Tíve’s sections just didn’t have the same tension, and so they had to go.

This was all interesting to me, but when it became obvious to me that I could pretty much lift out Tíve’s storyline without having to change much in the rest of the book, I knew I couldn’t keep the material. The other points of view were all tightly intertwined—when one of the characters acted, it affected the other characters. Yolanda’s secret has profound consequences for her son and granddaughter; Amadeo’s romance throws Angel’s world into disarray; Amadeo’s failure with his first windshield repair job threatens his mother’s career. Tíve’s sections just didn’t have the same tension, and so they had to go.

Writing a novel can also be a learning process, because no matter how informed by experience writing is, there’s always something outside of your own life that you need to tackle. What kind of research did you do during the writing process? What did you learn about the world that you didn’t know before?

I take a pretty as-needed approach to research, especially for a story like The Five Wounds, which takes place in a time and place I am familiar with. When I wrote a story about a twelfth-century Belgian holy woman, Christina the Astonishing, I was not only in direct conversation with the English translation of the source material, but I was constantly having to stop writing to look up things like, Would a regular person’s house have windowpanes? and What are all the parts of a medieval woman’s clothing called? It made for very stop-and-start drafting.

When writing The Five Wounds, I could go much longer without looking things up. I kept a AAA New Mexico roadmap and an Española Yellow Pages on my desk, and early in the drafting I read quite a bit about the history of penitentes in the region. Years ago, I worked as a grant writer for a nonprofit that ran a high school equivalency program for teen mothers, and I drew on site visits and research I’d done at the time. Once I started writing about [Angel’s teen parenting program] Smart Starts! I visited other teen parent programs both for research and as a visiting writer.

I definitely had to research windshield repair, which mostly involved watching YouTube videos. My windshield got dinged the other day, so I may draw on that knowledge and try to fix it, but I suspect I may be even less skilled than Amadeo.

Okay, final question (I always ask this one): Pick one of your characters and tell me: What is their favorite song? What’s a song they love but are embarrassed by?

Angel’s favorite song is totally Beyoncé’s “Irreplaceable.” Also “Survivor.” She secretly really, really loves “Call Me Maybe.”