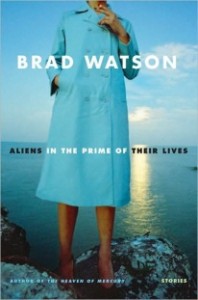

Full disclosure: Brad Watson’s Aliens in the Prime of their Lives was one of those rare books that I chose because of the cover. On it, a woman stands on a rocky coast—inches from the waves—smoking a cigarette in a trench coat. She seems on the cusp of something. That cigarette, I found myself thinking, might be her last. I hadn’t heard of Watson. I’d somehow missed both his first collection and his novel, The Heaven of Mercury, which was shortlisted for a National Book Award and now ranks in my top ten novels of the past decade. But, in that moment, at my local bookstore, I found the cover haunting, so I found a chair by a window and cracked the spine.

Full disclosure: Brad Watson’s Aliens in the Prime of their Lives was one of those rare books that I chose because of the cover. On it, a woman stands on a rocky coast—inches from the waves—smoking a cigarette in a trench coat. She seems on the cusp of something. That cigarette, I found myself thinking, might be her last. I hadn’t heard of Watson. I’d somehow missed both his first collection and his novel, The Heaven of Mercury, which was shortlisted for a National Book Award and now ranks in my top ten novels of the past decade. But, in that moment, at my local bookstore, I found the cover haunting, so I found a chair by a window and cracked the spine.

Watson’s characters are, as the cover promises, people on the brink. But, what makes his stories brilliant is the fact that they push through moments of desperation and depravity to a very human endurance, a defiant will to survive. The inner landscapes in Aliens are more like moonscapes; they are dark and disquieting, illumined by humor and quick flashes of love. While the circumstances of his characters—an almost feral girl who’s been raped by her father, a man who shoots himself in the foot to prove a point, a woman whose body’s been dumped in the dunes—are extraordinary, the slow burn of their anguish is all too universal.

Watson was born and raised in Meridian, Mississippi. And the Mississippi of today, and of the not-too-distant past, is the setting of much of his fiction. In Airships, Barry Hannah wrote that “In Mississippi, it’s hard to achieve a vista,” but Brad Watson does just that in this new collection. Not only is there a breathtaking sense of the Gulf Coast and the Delta in his writing, that geography is given depth—a hardscrabble social landscape inseparable from the place itself.

Watson’s debut collection, Last Days of the Dog-Men, won the Sue Kaufman Award for First Fiction. He followed-up Dog-Men with the lyrical The Heaven of Mercury. Some of the stories in Aliens harken back to the Gothic surrealism of The Heaven of Mercury, but what makes the collection such a pleasure to read is its diversity of style. “A Terrible Argument” is a darkly absurdist portrait of marriage. “Ordinary Monsters” is a collection of thematically-linked short-shorts. The title novella leans into experimental territory. They’re linked, though, by a common yearning: the yearning of exiles, aliens, for community, for companionship, for what once was.

I finished Watson’s collection in the Border’s coffeeshop that night. It was dark out, all yellow streetlights on snow banks. And as I walked home, the world seemed a bit strange, people’s faces a shade shy of ordinary. What can I say? I picked the book for the cover, but Watson’s writing tweaked something in my brain—the way I saw people, or myself. For a little while, he made me feel alien.

Interview:

Let’s begin at the beginning: how did you start out writing? Were you one of those five-year-olds hunting and pecking on a typewriter, preternaturally aware that writing was your calling?

No. I remember being seven and thinking I could never be a writer because my handwriting was so poor that the teacher made fun of me in class. I had no idea I could use a typewriter or something. Dim child – dreamy, but dim. I didn’t try to write a short story until I was nineteen, my first year in junior college, after spending a year in Hollywood trying to get into the movies. I was married, with a two-year-old son, and lucked into an honors English class, which is what got me interested in writing fiction. I didn’t write anything even close to a decent attempt at a short story until I was twenty-one.

You and Barry Hannah are from the same Mississippi city – Meridian. Jimmie Rodgers too! Is there something in the water? What was growing up in Meridian like?

There used to be, anyway, a lot of chlorine in the water. Barry was born there, in the same hospital I was born in, but really grew up in Clinton. Still, I like to note we had the same birthplace: the old Riley Hospital, a red-brick, two story, old-fashioned affair. They probably used ether, I don’t know. Maybe in the water, too. Growing up in Meridian was good and not so good. Good in that it’s a quiet little town with beautiful old turn of the century downtown buildings, a slow pace of life, lots of friendly people. Not so good in that there wasn’t a lot to do for teens, so we spent a lot of time drinking too much beer and crashing our cars and motorcycles. There was a great Little Theater, though, that I got involved in during high school, where you’d meet interesting people from the Navy Air Station just outside of town. May be why I tried to become a Navy pilot after graduate school.

There used to be, anyway, a lot of chlorine in the water. Barry was born there, in the same hospital I was born in, but really grew up in Clinton. Still, I like to note we had the same birthplace: the old Riley Hospital, a red-brick, two story, old-fashioned affair. They probably used ether, I don’t know. Maybe in the water, too. Growing up in Meridian was good and not so good. Good in that it’s a quiet little town with beautiful old turn of the century downtown buildings, a slow pace of life, lots of friendly people. Not so good in that there wasn’t a lot to do for teens, so we spent a lot of time drinking too much beer and crashing our cars and motorcycles. There was a great Little Theater, though, that I got involved in during high school, where you’d meet interesting people from the Navy Air Station just outside of town. May be why I tried to become a Navy pilot after graduate school.

It was a place full of your great assortment of characters, many of whom I got to meet via my status as a fourteen-year-old curbside beer salesman, which gave me access to miscreants and seedy old folks of various kinds. They all had stories, or they lived them out violently, tragically, comically.

You got your MFA from the University of Alabama in 1981, and your first collection, Last Days of the Dog-Men, come out in 1996. Nowadays, there’s a fair amount of pressure to graduate from an MFA program with a publishable manuscript and/or an agent to one’s name. Did you leave Alabama with the stories that would become Last Days of the Dog-Men? Can you talk a little bit about what you worked on in the interim between graduating and publishing, and what kept you writing?

Actually, I got the degree in 1985 – I took a while longer than I was supposed to, which was I think 1981 or ’82. Only two stories in Dog-Men were revised from my thesis. In those days, the pressure to leave with a manuscript was there, but there were a lot fewer places to publish it. Aside from New York, there weren’t nearly as many reputable small and independent presses as there are now. A friend’s agent turned down my collection so I left Tuscaloosa and worked as a journalist for three years, wrote ad copy for a year, taught English as an adjunct for three years, worked in a PR office for four years, and it was really during those last four or five years that I worked on the Dog-Men stories, although I’d drafted some of them during my week of summer vacation in the day jobs. I’d go to the beach, rent a cabin, write a draft per day on a manual typewriter on the porch and then tinker with them throughout the year. Some worked out, some didn’t. I never stopped trying to write, except for the three years as a journalist, when I really spent my free time repercolating, reconsidering what it was I wanted to write and how to do it.

Actually, I got the degree in 1985 – I took a while longer than I was supposed to, which was I think 1981 or ’82. Only two stories in Dog-Men were revised from my thesis. In those days, the pressure to leave with a manuscript was there, but there were a lot fewer places to publish it. Aside from New York, there weren’t nearly as many reputable small and independent presses as there are now. A friend’s agent turned down my collection so I left Tuscaloosa and worked as a journalist for three years, wrote ad copy for a year, taught English as an adjunct for three years, worked in a PR office for four years, and it was really during those last four or five years that I worked on the Dog-Men stories, although I’d drafted some of them during my week of summer vacation in the day jobs. I’d go to the beach, rent a cabin, write a draft per day on a manual typewriter on the porch and then tinker with them throughout the year. Some worked out, some didn’t. I never stopped trying to write, except for the three years as a journalist, when I really spent my free time repercolating, reconsidering what it was I wanted to write and how to do it.

I’ve always worked, from the time I was thirteen and fourteen. I worked and supported my young family during senior year in high school (we’d married between my junior and senior years, like the narrator of the title novella in Aliens in the Prime of Their Lives) as a construction laborer and carpenter’s apprentice. Then, after a year in Los Angeles working many different jobs, including garbage man in Hollywood, we went home and I began junior college and worked 30-35 hours a week in a lumber company wood shop. At the university, I worked two work study jobs (the director had pity on my finances) and worked summers in construction when I could. I value work, honorable work anyway, and don’t mind having to do it while being a writer, too. Although lately I’m wishing I could write full time so I hope I keep my health long enough to write well and long into retirement one day.

Has it been a struggle to achieve a balance between your writing and other jobs?

It’s always a struggle to balance writing and the day job, even when you have one of the better teaching jobs (if you put anything into it). I’m not a naturally organized or efficient person, so that makes it all the worse. Sometimes it’s harder to write as a teacher than it was as an ad writer or PR writer. The labor jobs, you really don’t have much energy left for writing during the week, so you hope you will be given the weekends by your spouse or partner.

I spent many years thinking about the possibility of the writer’s ideal day job. Really, I think I have to agree with what Shelby Foote once said to me, after criticizing me for taking a teaching job at Harvard. He said, “Why in the hell would you want to do something like that? If I had to work a job, I’d pump gas or something.” I was too embarrassed to say that I was already knuckled under to conventional bogus burdens such as health insurance, etc. And the truth is I’ve had more time to spend as a writer when I was a garbage man (wish I’d actually been a writer then, instead of an aspiring movie actor), or ditch digger on the construction site, hauling garbage away and such, or pumping aviation fuel at the local airport in Tuscaloosa – even if they were physically more demanding. Problem is, the airport job for instance, which I loved, paid just five dollars an hour and I had rent, child support, and so on. The longer a writer can put off succumbing to the so-called essentials in “contemporary society,” and the accompanying anxiety it all creates, the better. The longer you can be a bum, the better, as long as you write hard while you’re bumming.

I spent many years thinking about the possibility of the writer’s ideal day job. Really, I think I have to agree with what Shelby Foote once said to me, after criticizing me for taking a teaching job at Harvard. He said, “Why in the hell would you want to do something like that? If I had to work a job, I’d pump gas or something.” I was too embarrassed to say that I was already knuckled under to conventional bogus burdens such as health insurance, etc. And the truth is I’ve had more time to spend as a writer when I was a garbage man (wish I’d actually been a writer then, instead of an aspiring movie actor), or ditch digger on the construction site, hauling garbage away and such, or pumping aviation fuel at the local airport in Tuscaloosa – even if they were physically more demanding. Problem is, the airport job for instance, which I loved, paid just five dollars an hour and I had rent, child support, and so on. The longer a writer can put off succumbing to the so-called essentials in “contemporary society,” and the accompanying anxiety it all creates, the better. The longer you can be a bum, the better, as long as you write hard while you’re bumming.

So after twenty-two years as a teacher, do you identify yourself more as a teacher or a writer? How does teaching affect your writing? And what do you think is the most important thing to impart to a creative writing student?

I recently said, talking to some students at Montana, “No good writing, no good teaching.” I don’t think you can be a decent writing teacher if you’re not at least writing hard, even if you’re going through a time of not writing well. In the chicken-and-egg type view of this, writing definitely – how could it be otherwise? – comes before teaching. Teaching is a job, often a beloved one and always an important one, I think, very important, but you’re not really doing the students or yourself good service if you’re not always a writer first. I have what seems to me a kind of idealized love for my students, because of what they’re trying to do and because of how much I want them to have what they want. But I want them, also, to think of me as a writer who’s helping them become better writers, not so much as their “teacher.” I’m not teaching them much; I’m just trying to help them learn how to become better writers.

You’ve said in earlier interviews that reading inspires you to write. In a workshop I once took with Roxanna Robinson, she said that she only reads books that are very different from whatever she’s currently working on. I’m curious whether there’s anything you avoid reading when you’re writing, either because it’s too frustratingly brilliant or too similar to your own writing?

You’ve said in earlier interviews that reading inspires you to write. In a workshop I once took with Roxanna Robinson, she said that she only reads books that are very different from whatever she’s currently working on. I’m curious whether there’s anything you avoid reading when you’re writing, either because it’s too frustratingly brilliant or too similar to your own writing?

I think I heard Roxanna say that recently, too, when we were on a panel together in Tucson. I know what she means and agree that certain books can really mess with your head and your story if you read them while writing. On the other hand, I generally take the chance and read eclectically while I’m writing, because I never know what’s going to fire off some neuron and open it all up for me. The trick is to know when that’s what’s happening and when the bad version of it – such as wanting to write like another writer, especially one with a distinctive style – is happening, instead. Sometimes you can tell who a writer’s been reading when you read his or her work, and that’s often ultimately a little disappointing, because you feel that it’s detracting from the writer’s own fine sensibility a bit, even if it taught him something along the way.

And what are you reading now?

Butcher’s Crossing, by John Williams. I only recently read his beautiful novel, Stoner, and a friend encouraged me to continue with BC. Also, in preparation for a course in the novella next term, The Death of Ivan Ilych (or Ilyich, depending on the translation). I’ll be reading or re-reading several other novellas during the next month for the same reason, some older classics but also some new ones. Also the new stories in Barry Hannah’s last collection, Long, Last, Happy.

Butcher’s Crossing, by John Williams. I only recently read his beautiful novel, Stoner, and a friend encouraged me to continue with BC. Also, in preparation for a course in the novella next term, The Death of Ivan Ilych (or Ilyich, depending on the translation). I’ll be reading or re-reading several other novellas during the next month for the same reason, some older classics but also some new ones. Also the new stories in Barry Hannah’s last collection, Long, Last, Happy.

Speaking of Hannah, in a fascinating and hilarious radio session with Barry Hannah and Larry Brown in the late ‘90s (those were the days!) you talk about “clarifying for yourself just what your voice is like” and “listening to yourself closely.” It’s been thirteen years since that interview—is clarifying your voice still something that takes work, or has channeling it become easier over time?

I really try not to think about it; it would make me self-conscious about voice. I think it happens or doesn’t, at least for me. Stein and Hemingway and Carver and I guess Chekov and Babel before them were able to clarify for themselves a sense of their voices on the page, I think. But I’m not that distinctive. There’s a lyrical bent, which I try to contain these days in concision. Beyond that, I don’t think much about it.

Is there a story in Aliens in the Prime of Their Lives that seems to you most purely emblematic of your voice? Like if your voice is agave and your stories tequila, is there one that’s the 100% agave Gran Patron Platinum?

I think the title novella is probably more purely in my voice than a lot of work I’ve done. That, and “Alamo Plaza,” “Visitation,” “Water Dog God,” “Fallen Nellie,” maybe “The Misses Moses.” But the title novella seemed most intensely mine, I think. “Water Dog God” and “Fallen Nellie” are the lyrical elements in my head, whereas the others are more plainspoken. I like your analogy, by the way. I think I’ll get some more Patron.

We once bought a bottle of the local mescal in a little mountain town in Mexico. Tasted like armpit perspiration. We still have it. Saving it for that special occasion, you know. When we have a guest who’s one of those professional armpit sniffers for the anti-perspirant companies.

I think “gloaming” might be the word you use the most in your new collection, which, to me, seems appropriate since dusk is an almost otherworldly time, a state of limbo between night and day. Though religion is mostly absent from your stories, otherworldliness abounds, most obviously in the novella, and your characters are not without spirituality and superstition, visitations and dreams of the after-life. Could you talk a little bit about spirituality and what it brings to bear on your characters and their worlds?

I neither talk nor (I think) think much about spirituality. Maybe because I had a bad experience with organized religion during my first marriage and divorce, maybe because too many ‘new-agers’ talk about it in nauseating ways, so that I feel the word’s corrupted for me. I am fascinated by the various alternative states that exist within our minds or mental experience(s). How memory becomes myth. How dreams become confused with reality and memory. How fear and confusion alter or bend our sense of reality, just as I suppose happiness might.

In an earlier interview, you said that the eponymous novella grew out of a different novel in which aliens visit a minor character. How did that novel evolve into this novella?

The novel I stole the aliens idea from was set on the Gulf coast, and those aliens were different in that they actually abducted people through a vague (from my end) process of transforming them into a plasmic material that could be transported at unimaginable speed (such as the speed of thought transferred to the idea of intergalactic travel) to their own world, where the people would exist in a kind of laboratory, believing themselves to still be wholly physical and living out their lives as they’d always believed they would live them out. As in the novella, they were interested in where the human imagination takes a human life when unfettered by unexpected circumstances whether favorable or difficult. One of the problems with the novel was that I couldn’t get around to making the abductees into main or even interesting characters. It was a kind of confused project, from which I extracted something similar to one of the main conceits.

The novel I stole the aliens idea from was set on the Gulf coast, and those aliens were different in that they actually abducted people through a vague (from my end) process of transforming them into a plasmic material that could be transported at unimaginable speed (such as the speed of thought transferred to the idea of intergalactic travel) to their own world, where the people would exist in a kind of laboratory, believing themselves to still be wholly physical and living out their lives as they’d always believed they would live them out. As in the novella, they were interested in where the human imagination takes a human life when unfettered by unexpected circumstances whether favorable or difficult. One of the problems with the novel was that I couldn’t get around to making the abductees into main or even interesting characters. It was a kind of confused project, from which I extracted something similar to one of the main conceits.

Where does your imagination take your life when unfettered by circumstances?

Well, not to sound or be maudlin of self-pitying, but I can’t recall an adult time unfettered by circumstances. Because, I guess, I’ve spent a lot of energy creating fettering circumstances. Hefting one fardel or another to piss and moan about.

When you’re writing a novel with multiple points of view, how do you handle switching between them? Do you find yourself writing each character’s plotline separately, or do you move forward chronologically?

In The Heaven of Mercury, with its five or six different points of view, I often let myself write straight-ahead with a character regardless of chronology as it might exist in the completed draft. It was helpful sometimes to write about a character as if he or she were the only subject at hand, and to see how that affected the lives of other characters. In a similar way, if I came up with something I wanted to write right then, even though I knew or sensed it would come later in the novel, I went ahead and wrote it while I was excited about it. Most interested in it. I thought the energy I could tap into that way would make any additional logistical work worthwhile. And often doing that would open up possibilities in earlier parts of the book that I hadn’t thought of yet, or hadn’t thought of while I was writing those earlier parts. So I’m all for moving around freely within a book as you’re writing it. Plodding straight ahead, for me, can be restrictive and make me feel dull. It depends on the particular story, though. Some books may lend themselves to your working on things in a more orderly way.

In The Heaven of Mercury, with its five or six different points of view, I often let myself write straight-ahead with a character regardless of chronology as it might exist in the completed draft. It was helpful sometimes to write about a character as if he or she were the only subject at hand, and to see how that affected the lives of other characters. In a similar way, if I came up with something I wanted to write right then, even though I knew or sensed it would come later in the novel, I went ahead and wrote it while I was excited about it. Most interested in it. I thought the energy I could tap into that way would make any additional logistical work worthwhile. And often doing that would open up possibilities in earlier parts of the book that I hadn’t thought of yet, or hadn’t thought of while I was writing those earlier parts. So I’m all for moving around freely within a book as you’re writing it. Plodding straight ahead, for me, can be restrictive and make me feel dull. It depends on the particular story, though. Some books may lend themselves to your working on things in a more orderly way.

Each of your stories explores the trying relationships between loved ones – whether between spouses or parents and children – and memory hangs heavy over your characters. Many of them live almost in a state of limbo, suspended between past and present. Do these themes arise naturally in your writing, or did you set out to write a collection that focuses on them?

Usually, I feel lucky to gather presence of mind enough to finish anything. I’m very scatter-brained, day-dreamy. But some of this involves being a little obsessed with the past – my own, my family’s, the general past. So, yes, I suppose it’s natural that this comes out in my stories. I was conscious of being preoccupied with the idea of memory as I wrote most of the stories in Aliens, and it’s kind of impossible for me not to be preoccupied with broken families and difficult relationships since there’s been so much of that in my own life, I must admit. But, no, I can’t really say I was thinking of each story as part of a larger body of work as I wrote it. It takes too much of a concentrated effort to get into and get all of each story onto the page, and I can’t be thinking of other stories while I’m doing that, not in any substantial way, in any case.

All of the characters in Aliens in the Prime of Their Lives have weaknesses. Many display cruelty. The narrator of “Water Dog God” admits to coveting his young cousin, and then drowns her. The husband in “A Terrible Argument” threatens his wife with a gun (and makes his dog’s life a living hell). Yet you manage to evoke a sense of pathos in your reader for the depraved, the cruel, and the ridiculous. Is this authorly caring something you ever have to work at? Is there ever a character who challenges your empathy?

Wait – that character drowns his uncle, not the niece. Her death is an accident.

Wait – that character drowns his uncle, not the niece. Her death is an accident.

I don’t think I’ve written about, nor would I write about, a character who would challenge my ability to empathize (any more than it’s always a challenge, of course) because I wouldn’t be interested enough in such a character to write about him or her. Helen Vendler once said to me that sociopaths, for instance, are inherently uninteresting. They of the empathy void.

I can’t imagine anyone being a fiction writer, though, if he or she was overly moralistic in attitude toward people and their mistakes. If that’s your bent, you’d do better as a cop, I guess, than a writer. It’s the mistakes, or the trouble they make or find themselves in, that make the characters interesting in the first place.

Many of your stories are set on the Gulf coast. In The Heaven of Mercury, it’s the Gulf of the turn of the 20th century and the 1950s. In Aliens, both “Fallen Nellie” and “Alamo Plaza” are Gulf stories set in the past. I know some of your work is informed by the time you spent writing historical features for a newspaper in the region. What draws you to the history of the Gulf? Are you interested in writing about the modern Gulf Coast, especially given its calamitous recent past?

My interest in that place, aside from childhood memories such as the ones that “Alamo Plaza” grew out of (you can tell I don’t care if I end phrases or sentences with prepositions), did come from working as a reporter there during the 1980s, and living there for a while in the late ’90s, splitting time between there and the northeast. I was writing about a place very much in the process of what seemed to me – yes, calamitous is the word, and not just the hurricane(s) and oil spill(s) – change, with developers building too much too fast, threatening the life of the very paradise they were exploiting. Talking to people who’d lived there for generations made me even more sympathetic to the danger of it all.

I am interested in writing about the modern Gulf coast, for those same reasons. The failure of my aliens-shenanigans novel hasn’t stopped me from working when I can on another novel set there, during the present. I’d also like to write more set in the past there, too.

So is that what you’re working on now?

I’m working on a novel set in 1970s Mississippi, but as always I have other projects going: a novel set in a mid-sized Alabama city, a kind of violent satirical farce; a kind of a crime road novel, a novel about a woman in Mississippi whose life spanned 1888 – 1976; and a few new short stories.

Further links and resources:

Brad Watson / Photo by Lindsay Beamish

I’ve spent many, many days and nights in motels, some cheap and some average, a couple nice ones, with my son from my second marriage. Owen’s a connoisseur of motels, has his own priorities about what’s good and what’s bad, and it’s interesting to see how the priorities have changed over the past few years. For instance, anything that seemed to have what I deemed “character” (something that reminded me of motels from my own childhood, for instance) was out; now, he’s a little more open to that, but sometimes I think this is only so that he can educate me, pointing out once we’re in there just how run-down and crappy the place actually is. In any case, I wanted to write a story about a divorced father spending time with someone he loves most in the world, his child, in crappy, seemingly soulless places. The fact that Loomis, in this story, does not deal with it very well is a response from the more pessimistic, darker side of myself. I’m not exactly sure where the lighter, more optimistic side of myself resides, although I know it usually doesn’t involve motels and spending money on them. Eating a great meal with my son(s) and other family, is good. Great long walks in the Wyoming mountains, that’s good. Owen loves that, too, as does my older son, Jason. But this is a story about the difficult part of visiting a child of a busted marriage. The bad motels, the dislocation, the anxiety it all creates, together with memories of having once visited several roadside psychics (for a magazine article) who all predicted sad things for my current marriage—these seemed to be the stuff of the story. That said, I wrote the first draft longhand in the backyard during a wonderful summer in Wyoming when Owen was staying with me here, in our house, and having a great time biking and hiking with me in the Medicine Bow National Forest every day, eating good homecooked meals every night. It may be the contrast between such good times and such not-so-good times helps a writer to reimagine the hard times in more vivid detail. The detachment is critical, I think, for me.

Bookmark-Brad Watson from Bookmark CPTR on Vimeo.