Editor’s Note: This essay was originally posted on our blog on March 2. However, in an effort to celebrate Barry Hannah’s life and work and craft, we have decided to republish it in an expanded form. Thank you.

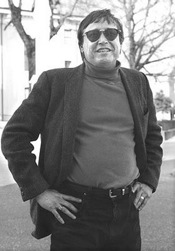

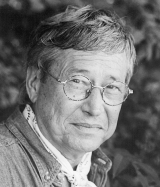

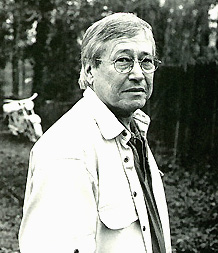

This morning I woke to hear the sad news that Barry Hannah had died. He was 67, and the apparent cause was a heart attack, according to the Jackson Free Press. Barry had had several bouts with cancer over the last ten years, yet I was still shocked to hear that he was gone. I guess I’d come to think of him as oddly invincible.

This morning I woke to hear the sad news that Barry Hannah had died. He was 67, and the apparent cause was a heart attack, according to the Jackson Free Press. Barry had had several bouts with cancer over the last ten years, yet I was still shocked to hear that he was gone. I guess I’d come to think of him as oddly invincible.

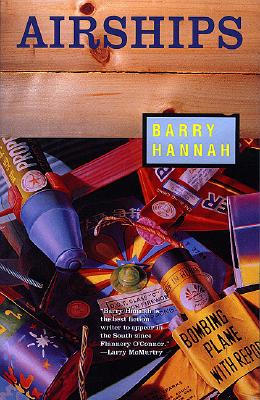

Maybe it’s also because Barry’s prose felt like it was carved out of stone. Not weighty, but permanent. With a hint of the divine. That crazy Old Testament kind of divinity that’s equal parts kindness and cruelty, lust and humor. Especially humor. Who else could open a collection of stories as Barry did his 1978 masterpiece, Airships, with a passage like this:

When I am run down and flocked around by the world, I go down to Farte Cove off the Yazoo River and take my beer to the end of the pier where the old liars are still snapping and wheezing at one another. The line-up is always different, because they’re always dying out or succumbing to constipation, etc., whereupon they go back to the cabins and wait for a good day when they can come out and lie again, leaning on the rail with coats full of bran cookies. The son of the man the cove was named for is often out there. He pronounces his name Fartay, with a great French stress on the last syllable. Otherwise you might laugh at his history or ignore it in favor of the name as it’s spelled on the sign.

I’m glad it’s not my name.

For many young writers, this was our first encounter with Barry’s work. His voice hooked you deep. I was in college when this book was pressed upon me and my now brother-in-law, Dean Bakopoulos, by Elwood Reid. This was the late 1990s. Dean and I were undergrads at the University of Michigan, both eager to be writers but still sorting out exactly how to go about the task. Elwood, who was finishing his MFA at the time, took us under his wing to show us the way. For Elwood, who’d once been a college football player, that meant work. Lots of work. And by “work” I mean reading. Barry Hannah. Larry Brown. Rick Bass. Amy Hempl. Mary Gaitskill. The collections piled up.

But there was something about Barry’s work that stood out. An urgency in the prose that punctured your heart. “Water Liars” is a great story, but when I hit the second one in the collection, “Love Too Long,” I was gone.

My head’s burning off and I got a heart about to bust out of my ribs. All I can do is move from chair to chair with my cigarette. I wear shades. I can’t read a magazine. Some days I take my binoculars and look out in the air. They laid me off. I can’t find work. My wife’s got a job and she takes flying lessons. When she comes over the house in her airplane, I’m afraid she’ll screw up and crash.

For a college kid, Barry bored down through the mantle to the molten core of what it meant to feel. He still does. Typing his words you can feel the anguish and energy. Further down this page, the narrator, nearly beside himself, writes, “I want to sleep in her uterus with my foot hanging out.” It’s an image that makes you wince, but it’s also oddly tender. What it is is honest.

I experienced both sides of Barry’s honesty when I was a student of his in 2003 at the Sewanee Writers’ Conference. The day of my workshop, we moved around the table in usual fashion–what’s working, what isn’t. Janet Peery was co-teaching the session, and among the group were writers such as Ben Percy, Lisa Lerner, Dave Koch, Forrest Anderson, Karen McKinnon, and John Struloeff. I was giddy to be in the room with one of my literary heroes. And while the others were offering feedback on my writing, I stole the occasional glance to see how Barry was reacting. Most of the time he spent flipping fairly idly through my pages. So perhaps I shouldn’t have been surprised when, upon his turn to speak, he began gutting the opening paragraph of the prologue to the novel I’d been working on. Sentence by sentence, word by word, he worked like a butcher, cutting back the fat. Let’s just say that there wasn’t much meat left when he got down to the bone. Or, rather, he showed me that there hadn’t been much muscle to begin with. Would it be too much to say I felt eviscerated along with my work?

Yet it wasn’t cruel. It was honest. And when the furnace of my face cooled I saw that he was mostly right.

But I didn’t want my teacher and literary icon to have this impression of my work (I swear, the rest was better). So, later that night, during the evening cocktail hour, I slipped him one of my stories, one which I’d been carrying around for the better part of an hour rolled up in my fist, wrinkled and creased. And when I finally got the nerve to give it to him, I tried hard to assure him that this wasn’t extra work. Nothing I was looking for feedback on. Nothing he even had to read during the conference. Just, well, something I wanted him to have. And I’m sure I must have said something inane like, “I hope you enjoy it.” As if it were some sort of gift. Walking away, I was certain that I had made things worse.

But I didn’t want my teacher and literary icon to have this impression of my work (I swear, the rest was better). So, later that night, during the evening cocktail hour, I slipped him one of my stories, one which I’d been carrying around for the better part of an hour rolled up in my fist, wrinkled and creased. And when I finally got the nerve to give it to him, I tried hard to assure him that this wasn’t extra work. Nothing I was looking for feedback on. Nothing he even had to read during the conference. Just, well, something I wanted him to have. And I’m sure I must have said something inane like, “I hope you enjoy it.” As if it were some sort of gift. Walking away, I was certain that I had made things worse.

And the next morning, when Barry found me at breakfast, I was more than sure of my mistake. “Here, kid,” he said, handing the story back to me across the table. Without another word, he walked off. Cut to blistered cheeks again. In front of an entire table of your peers, Barry Hannah has just returned the story you gave him the evening before, the story meant to redeem you. “Thanks, but no thanks,” is what you read in this gesture. And in that moment you imagine escaping back to Michigan several days from now–it’s a nice, long trip from Tennessee, one that will give you plenty of highway to replay this moment over and over and over.

Yet when I unrolled my story, he’d scrawled this across the top in loopy script: “I enjoyed greatly. I’m nominating it for Best New American Voices.” Simple. Generous. An unasked for kindness. And I realized that it wasn’t about you in that classroom; for Barry it was about the work.

At the end of his fantastic interview with Barry in Tin House last year, Tom Franklin asked the author how his teaching has changed over the years. Here is Barry’s response:

It’s gotten a lot simpler. The things that I do well in my own work, I didn’t ever think about, because I’d been trained on good storytelling and helped by a few good teachers. But outside of beginning, middle, and end and “thrill us,” what is there to teach? There’s no theory, there’s nothing that guarantees publication. I’ve never been interested in intellectual experiments. I prefer to thrill people in their guts rather than in their heads. With some of the MFA writing I read now, I wonder, “My God, didn’t anybody get it across that you’ve got to entertain?” You’re fortunate if what entertains you entertains the crowd also.

It’s impossible for me to behave as if I were thirty-five when I was writing Airships–it’s impossible. And I must say you don’t necessarily gain a lot by age; you sometimes are in danger of becoming the old hack plagiarizing his own former work. That’s probably why the old often bore people, they just say the same damn things over and over, and they just deal in truisms. That’s the mass of America, one truism after another. For instance, the word motherfucker is a truism now. It’s just empty. It used to be an exciting word because it’s the worst thing you can imagine, you know? But now it’s just a weak flat noun.

It may be just my time of life, but I’ve been teaching better, I hope. My essays have gotten better. But what I want is what I had in Airships and High Lonesome and Bats Out of Hell and Captain Maximus: joy. Joy, just joy, just jump in there because you’re onto it. You’ve gotta write it. You feel it deep in the pit of your stomach.

Thank you, Barry.

From the Sewanee Writers’ Conference on March 2, 2010:

We are saddened to hear that Barry Hannah, a great friend of the conference, passed away on Monday, March 1. Barry was a member of the fiction faculty at Sewanee in 1999, 2000-2003, and 2006. He visited the conference to read in 2004, 2005, 2007, and he was scheduled to read at this summer’s conference.

We are saddened to hear that Barry Hannah, a great friend of the conference, passed away on Monday, March 1. Barry was a member of the fiction faculty at Sewanee in 1999, 2000-2003, and 2006. He visited the conference to read in 2004, 2005, 2007, and he was scheduled to read at this summer’s conference.

One of the finest writers in American letters, Barry Hannah published eight novels—Geronimo Rex (Alfred A. Knopf, 1972—winner of the William Faulkner Prize), Nightwatchmen (Viking, 1974), Ray, The Tennis Handsome (Alfred A. Knopf, 1981, 1983, respectively), Boomerang, Never Die (University Press of Mississippi, 1986 and 1990), Hey Jack! (Dutton, 1992), and Yonder Stands Your Orphan (Grove/Atlantic, 2001). His story collections are Airships, Captain Maximus (Alfred A. Knopf, 1978 and 1985), Bats out of Hell, and High Lonesome (Grove/Atlantic, 1993 and 1996).

Barry’s readings at Sewanee were always the highlight of the conference, and his openness with all participants spoke to his generosity. We will miss him greatly.

- You can read the New York Times obituary here.

- The Mississippi Review has an interview with Hannah from 1996.

- At Wired for Books, you can hear Hannah read from his stories “Water Liars” and “That’s True”.

- The Oxford Conference for the Book, which begins March 4th, is dedicated to Barry Hannah. Writers such as Tom Franklin and Amy Hempel will discuss his life and work.

Postscript:

Like many writers who’ve been inspired and influenced by Barry’s work, I’ve spent much of the past few days pulling his books off the shelf to reread favorite stories and passages. I’ve been carrying my copy of Airships around with me since Tuesday, like some sort of totem. It’s inscribed with a simple message from Barry: “Yours to hell and back.” Part promise, part confession. It’s a simple line, but it matters. And it reminded me how much Barry cared about the line. Particularly those clean, simple, honest lines: “I’m going to die from love.” Who else could end a story like that and truly mean it?

I think it was the honesty of Barry’s work that drew so many of us to him. And I also think the many memorials and tributes that have poured out since news of his death are a testament to not only his great talent, but also his generosity and his kindness. He had damn high standards, but as long as you were willing to be true to the art you were good in his book.

And so to celebrate Barry’s influence, and also with the hopes of bringing new readers to his fiction, we decided to republish this essay as a feature. We also wanted to take this opportunity to recognize some of the sites that have been paying homage to Hannah this week, as well as those publications that have supported his work for years. Thank you.

Matthew Simmons from HTML Giant was one of the first to bring news of Barry Hannah’s passing, and he has a wonderful tribute to the author that unfolded as we learned of his death.

Matthew Simmons from HTML Giant was one of the first to bring news of Barry Hannah’s passing, and he has a wonderful tribute to the author that unfolded as we learned of his death.- Alec Niedenthal subsequently put together a collection of remembrances for the same site entitled “There are Dry Tiny Horses Running in My Veins: Mourning Barry Hannah,” which includes not only his recollections and those of Michael Bible and Lincoln Michel, but also a selection from this post of mine. Many thanks for that.

- Lincoln Michel has a great round-up of links to work by and about Hananh on The Faster Times.

- One of those pieces that stands out is a wonderful compilation in Vanity Fair by Claire Howorth, which includes remembrances of Hannah by such writers as Richard Ford, Jim Harrison, Amy Hempl, Matt Wieland, and Wells Tower.

- There’s also a great essay on The Rumpus by A.N. Devers about Hannah, grieving, and the memory of our teachers.

- And a wonderful anecdote about idolizing Hannah from Kevin Wilson on his blog.

- Just a few weeks ago Elwood Reid wrote a brief review for Three Guys One Book about how the collection Airships affected him when he read it for the first time. He writes, “Airships didn’t change my life, it rewired my idea of the sentence and what a short story could and should do.”

- To hear Hannah talk about his work and the writing life, you can read Tom Franklin’s 2009 Tin House interview, or Mark Smirnoff’s 2001 interview from The Oxford American.

- Wells Tower also has a beautiful portrait of Hannah and the trip he took with the author to visit Larry Brown’s grave in 2008 for Garden & Gun.

- For more on Hannah’s writing style itself, read “Among Mutinous Helium Bursts Around Saturn: Barry Hannah’s dangerous syntax,” an essay by Jamie Quatro, which appeared in the September 2009 Southern Lit issue of The Oxford American.

- And last, but certainly not least, here is “Water Liars,” the opening story from Barry Hannah’s 1978 collection, Airships (reprinted with permission from Grove Press on the Garden & Gun website).

Of Special Note: Hannah’s influence on American Letters will be celebrated in Oxford at the 17th Annual Oxford Conference for the Book, which begins March 4. The conference had been dedicated to the author’s work and life, and will take place as planned. Scheduled to speak are such writers as Beth Ann Fennelly, Tom Franklin, John Grisham, Hendrik Hertzberg, Mark Jarman, JoAnne Prichard Morris, Mark Richard, Cynthia Shearer, Wells Tower, and Steve Yates. Here is Richard Howorth’s tribute, which had originally been written to be delivered at the conference. Howorth is the owner of Square Books in Oxford, Mississippi, and a long-time friend of Hannah.

Of Special Note: Hannah’s influence on American Letters will be celebrated in Oxford at the 17th Annual Oxford Conference for the Book, which begins March 4. The conference had been dedicated to the author’s work and life, and will take place as planned. Scheduled to speak are such writers as Beth Ann Fennelly, Tom Franklin, John Grisham, Hendrik Hertzberg, Mark Jarman, JoAnne Prichard Morris, Mark Richard, Cynthia Shearer, Wells Tower, and Steve Yates. Here is Richard Howorth’s tribute, which had originally been written to be delivered at the conference. Howorth is the owner of Square Books in Oxford, Mississippi, and a long-time friend of Hannah.