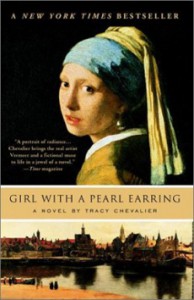

Like so many other people, I was caught up in the enthusiasm for Tracy Chevalier’s Girl With a Pearl Earring when it came out in 2000. I loved the way the novel captured the stark world of 17th-century Delft and the chaos of Vermeer’s household, and brought to life the beautiful girl in the painting. I admired the restraint of the novel, too, how sexual tension builds between Vermeer and Griet and they don’t act on it – though the scene where he pierces Griet’s ear has stayed with me for years.

When I moved to The Netherlands for a couple of years, one of my first goals was to visit the Mauritshuis, or Royal Picture Gallery, where Vermeer’s wonderful painting lives. I walked past years of Dutch Masters, of meticulously painted cows, still lifes of dead hares with fruit, and paintings of cloudy, flat landscapes before finding her. It was like seeing a friend’s picture on the wall, so fully had Chevalier drawn her characters and filled out a world in her book.

I went on to enjoy Chevalier’s subsequent novels: Falling Angels, Lady and the Unicorn, Burning Bright and, most recently, the fascinating Remarkable Creatures (Dutton/Penguin). Reading Remarkable Creatures reminded me that there’s something timeless about a beach; hunting for fossils must be one of the few things we do the same way now as Mary Anning and Elizabeth Philpot did it 150 years ago. Trust Tracy Chevalier to bring their world alive for us.

In June 2009, I interviewed Tracy Chevalier in her home. Sitting with Chevalier in her homey, book-filled Victorian townhouse in North London, I found her very alive to the world at large, attuned to the subtleties and human drama of the past, and able to draw them fully in the present.

Interview:

Felicity Librie: When did you decide that you wanted to be a writer?

Tracy Chevalier: You know, that’s a difficult question. You would think it’d be easy, but it isn’t. I guess I really only thought of myself as a writer once I had a book published, and even then I felt a little bit like a fraud. I don’t know, like, somebody’s going to find me out. But I talked about being a writer when I was a kid because I loved books so much and I was one of those readaholics. I wasn’t sporty, I was fat, I lay on my bed all day and read, and I think I wanted to be involved in the world of books somehow, and so I used to say I wanted to be a writer or I wanted to be a librarian because that was my source of books at that time: a library. I knew nothing at that time about publishing so I just thought it was one or the other.

When I was a teenager I did some writing, but I also started editing a literary magazine at school. So then I discovered there was this thing called an editor, and publishing, and I thought, well actually, I want to be that, because I had that typical teenage girl’s loss of confidence, and I didn’t think that I would be a very good writer, but I could work on other people’s stuff. And so when I went to Oberlin I majored in English, and I did go into publishing for several years. But in the back of my mind was this little itch, like, maybe I’ll write a short story. I didn’t have an idea to write a novel—it was always going to be small—and I remember sending a postcard, after I graduated from college, to one of my professors, saying, “I have an idea for a short story. I’m going to write it.” I don’t know why I said that to him. Maybe it was because he was a writer himself and by sending it to him, I was forcing myself to say, got to do it now, you’ve told [poet] David [Young] you’re going to. And I worked full time, and slowly started putting together stories on the side. But where that came from, I don’t know—that desire to do that. Even then I didn’t call myself a writer. It was only as they started to accumulate over the years that I went very gradually in that direction.

Girl With a Pearl Earring was a critical and popular success, selling 4 million copies worldwide, and going on to be adapted for screen and stage. This must all have been incredibly exciting, but how did it affect you as a writer?

It was pretty scary. On the one hand it was wonderful to have that validation, and to know that I had a readership. That something I had created in a little room in my mind, and in a physical little room, could go out there and really touch people—it was just astonishing. I also underestimated how popular Vermeer is. So that was a surprise, and I couldn’t have done it without him! But it made it hard to write the next novel. When you have a success, your subsequent books are always compared to that. I had critics and readers say, “This isn’t like Girl With a Pearl Earring; why not?” Or, “This is too much like Girl With a Pearl Earring, she’s retreading old territory.” I try hard not to listen to all that but I was very aware, when I wrote Falling Angels, the book after Girl With a Pearl Earring, that I didn’t want to write Woman with a Pearl Necklace—that would be the sequel! (Laughs.) I had to get away from that, so I wrote something really different, set in Edwardian England, with twelve different voices. It’s more of a big genre painting than a focused Vermeer. Some things about it worked and some didn’t. I try not to compare, even though everybody else does.

It was pretty scary. On the one hand it was wonderful to have that validation, and to know that I had a readership. That something I had created in a little room in my mind, and in a physical little room, could go out there and really touch people—it was just astonishing. I also underestimated how popular Vermeer is. So that was a surprise, and I couldn’t have done it without him! But it made it hard to write the next novel. When you have a success, your subsequent books are always compared to that. I had critics and readers say, “This isn’t like Girl With a Pearl Earring; why not?” Or, “This is too much like Girl With a Pearl Earring, she’s retreading old territory.” I try hard not to listen to all that but I was very aware, when I wrote Falling Angels, the book after Girl With a Pearl Earring, that I didn’t want to write Woman with a Pearl Necklace—that would be the sequel! (Laughs.) I had to get away from that, so I wrote something really different, set in Edwardian England, with twelve different voices. It’s more of a big genre painting than a focused Vermeer. Some things about it worked and some didn’t. I try not to compare, even though everybody else does.

It’s interesting that you mention the twelve viewpoints, because Girl With a Pearl Earring is the only one of your novels that has a single point of view. All the others use more than one voice. How do you decide about that?

Sometimes it’s obvious right away, and other times it only works later. Originally I wrote Falling Angels in third person, but with little sections in the first-person voices of three main children. I found, as I was writing it, that the third-person sections were boring to write—although there is boredom in all writing, so I wasn’t overly worried about that. But then I would get to the first-person sections, which I called voice sections, and say, “Oh, it’s a voice section today, thank God, this’ll be fun.” Of course alarm bells should have gone off. When I reread the first draft I cried at the end. It was boring, dead weight, terrible. Then I looked it over and thought, there’s nothing wrong with the story except the way it’s told. Maybe I should take a cue from my pleasure in writing the first-person sections. Maybe it should all be in first person, a cacophony of voices. I took the draft, and it was like taking a vase and setting it down so hard it shatters, then putting the pieces back together in a different way. I rewrote the whole thing in first person with all these different voices. I had the idea when, just as I was finishing the first draft in third person, I read Barbara Kingsolver’s The Poisonwood Bible, which uses five different voices beautifully. It’s a wonderful book, using multiple voices very successfully, and I thought, “Oh, that’s an interesting technique, I wonder if I should take the kids’ voices I’ve already written and have the three of them tell it.” It just felt right.

Sometimes it’s obvious right away, and other times it only works later. Originally I wrote Falling Angels in third person, but with little sections in the first-person voices of three main children. I found, as I was writing it, that the third-person sections were boring to write—although there is boredom in all writing, so I wasn’t overly worried about that. But then I would get to the first-person sections, which I called voice sections, and say, “Oh, it’s a voice section today, thank God, this’ll be fun.” Of course alarm bells should have gone off. When I reread the first draft I cried at the end. It was boring, dead weight, terrible. Then I looked it over and thought, there’s nothing wrong with the story except the way it’s told. Maybe I should take a cue from my pleasure in writing the first-person sections. Maybe it should all be in first person, a cacophony of voices. I took the draft, and it was like taking a vase and setting it down so hard it shatters, then putting the pieces back together in a different way. I rewrote the whole thing in first person with all these different voices. I had the idea when, just as I was finishing the first draft in third person, I read Barbara Kingsolver’s The Poisonwood Bible, which uses five different voices beautifully. It’s a wonderful book, using multiple voices very successfully, and I thought, “Oh, that’s an interesting technique, I wonder if I should take the kids’ voices I’ve already written and have the three of them tell it.” It just felt right.

I knew, when I came up with the idea for Girl With a Pearl Earring, that I didn’t want it to be about Vermeer, I wanted it to be about her. She would have a voice and a story, which she hadn’t ever had. Plenty has been written about Vermeer, but not about his models. It seemed perfectly clear that it should be from her point of view.

My latest book, Remarkable Creatures, is particularly about a woman named Mary Anning, the fossil hunter, but I knew I wanted there to be a different perspective. Mary was not educated, she didn’t travel, and I felt like we as twenty-first-century readers need a broader view. Also, in religious terms, there were people who saw fossils as a challenge to their ideas about religion, and I wanted to be able to present both sides: people who felt, God created fossils and it didn’t affect their religious beliefs; and those whom fossils did challenge. So I wanted two sides of the argument, and I found out that Mary had this friend who was a middle-class woman twenty years her senior, named Elizabeth Philpot. It made perfect sense to have the two of them tell the story and get a more complete picture. So it comes organically out of the story, but you don’t always know right away. Sometimes it takes a lot of fiddling around, or rewriting a whole draft from a different point of view.

You’ve written about real characters before, such as Johannes Vermeer and William Blake, but they were tangential characters in those novels. Mary Anning is very much center stage in Remarkable Creatures. Was it a constraint to write about a real person, about whom quite a lot is known?

Mary Anning, prior to 1842

It was both an advantage and a disadvantage. The advantage is that you don’t have to make it up, which is great, because my imagination is limited! I had the skeleton structure of her life, where she was at more or less any given period; she didn’t move around much, and lived in Lyme Regis all her life. There were highlights of her life, so the peaks are of the story are built in, and that’s great. The disadvantage is that those peaks don’t always happen the way we as readers would like them to. I had to fudge the chronology a little bit, more in this book than in other books.

Vermeer and Blake are both central to the concept of their books, but they’re not the main players, and it’s much easier to make up stuff around them without it actually affecting their chronology. Whereas with Mary Anning, between two important things that happened there’d be a three year gap. And I’d go, “Oh, three years? This is outrageous!” The thing is, back then people had very different lives from us. She used to go out on the beach every day, and the same things would happen year after year. Our lives are much more varied than that, and we’re used to reading about people with more varied lives.

Day after day isn’t great for narrative. So in the first draft I kept all the dates, then I put it all together and thought, oh, this drags a bit—who needs to know that this happened and then there were three or four years before that happened? And I thought: why don’t I just take off the dates? It was an incredible liberation. All my other books have dates that separate the sections, and it’s very clear when things take place. This time I’ve stripped them all out, and it was a great relief. There are three dates that are mentioned, one on which an auction takes place, one when she finds an ichthyosaur, and one when she finds a plesiosaur. I think those are the only specific dates in the book. Everything else is kind of a mishmash. Readers don’t mind it at all—no one’s said to me, “I don’t get this, you know that three years have gone by there?” Once you look at it in a different way and allow yourself that leeway, it makes it a lot easier.

Do you always start with research?

More or less. I read about the period when I’m setting it, and I go to see the places, check out where the scenes are going to be. So for The Virgin Blue, my first novel, I had the idea and did a bit of research, and then I went down to southern France and found a town for Ella, the contemporary character, to live in. I actually rented a car at Toulouse airport and then drove with a map and went into all these small towns. About the third or fourth one I visited, I drove into it and I thought, yeah, okay, she’s going to live here. And that’s a lot of time, you know, but it all starts with researching, taking notes. I start to write without having completed the research, because once you start writing, it opens up a lot of other questions that you need to do research on, and so I feel like my research process is never complete. In fact from each novel I’ve worked on I still have books on my bookshelf that I ought to have read! (Laughs.)

More or less. I read about the period when I’m setting it, and I go to see the places, check out where the scenes are going to be. So for The Virgin Blue, my first novel, I had the idea and did a bit of research, and then I went down to southern France and found a town for Ella, the contemporary character, to live in. I actually rented a car at Toulouse airport and then drove with a map and went into all these small towns. About the third or fourth one I visited, I drove into it and I thought, yeah, okay, she’s going to live here. And that’s a lot of time, you know, but it all starts with researching, taking notes. I start to write without having completed the research, because once you start writing, it opens up a lot of other questions that you need to do research on, and so I feel like my research process is never complete. In fact from each novel I’ve worked on I still have books on my bookshelf that I ought to have read! (Laughs.)

How do you use your research, which might be quite dry and academic, and bring it to life the way you do? What’s the mechanism for taking facts and using them to recreate the past in a way that’s vibrant?

I put the story first, and the characters. The history always has to be secondary. I don’t want to be a teacher, I want to be a storyteller, and I want to prop up what I write with something that’s going to give it validity. That’s where the history comes in. I wasn’t a history major; I wasn’t that interested in history until I was in my thirties, and even now, I’m only interested in history when I’m writing a book. I’m interested in that era and I want to read everything about it, find out about it, sort through all the junk to find the little glittering things that are going to work. That sorting gives me the confidence to set something during a particular period. It makes me know, when a character walks into the house, what the dimensions of the rooms are, what she’s wearing, what she’ll do when she comes in—does she take off a hat and gloves, what kind of shoes does she have, what’s she going to eat? When I’m writing books I tend to see history not as about who’s prime minister or president at the time, but more about what people’s everyday lives were like, and how they differed from ours.

You’ve talked before about how you like to get your hands dirty when you’re researching a novel. You took painting classes when you were writing Girl with a Pearl Earring and you went to a tapestry studio for The Lady and the Unicorn. Apart from looking on the beach for fossils, what did you do for Remarkable Creatures?

That’s pretty much what I did! Mary and Elizabeth were very interested in fossils, that was their obsession, and so I had to spend a long time on the beach, looking. It requires a lot of patience, a way of being that doesn’t happen just going out once. I had to go a lot. I’ve got a lot better at finding things than I was at the beginning, because of all the time I put in. And there’s a whole gallery in the Natural History museum of London which is full of the ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs that Mary Anning found. I spent a lot of time looking at them. Other than that, Elizabeth Philpot collected a lot of fossil fish, and when she died her nephew gave her collection to the Natural History Museum in Oxford. They have her stuff in all these big trays in back rooms, and I spent a very happy day pulling them out and looking. Some of the labels are in her hand, they’re original, and it was so amazing to hold these things, to hold what she found, prepared and cleaned, and studied, and wrote the labels for. And there’s the label, still there. I always love the hands-on, not just doing but also feeling. It’s like a talisman to touch something that my characters have touched. William Blake had a notebook that he used to write his poems in. They have it at the British Library, and when I was researching Burning Bright, I managed to talk them into letting me look at it, and hold it, and turn pages. It was so amazing.

Your last two novels have featured towns in Dorset (on the English south coast), where you spend a lot of your time—Piddletrenthide in Burning Bright, and Lyme Regis in Remarkable Creatures. How much does your knowledge of those modern settings underpin your creation of the historical settings?

Hugely. I could have chosen to have the made-up family in Burning Bright come from anywhere. I wouldn’t have used Piddletrenthide if I didn’t know it, but I wanted them to be from the countryside, and move to London, where they end up living next to William Blake. And the one bit of English countryside I know best is Dorset. We bought a cottage down there right at the time when I started researching Burning Bright. So I thought, maybe I’ll set it nearby, since I know the area, and then I started getting interested in Piddletrenthide’s history.

Hugely. I could have chosen to have the made-up family in Burning Bright come from anywhere. I wouldn’t have used Piddletrenthide if I didn’t know it, but I wanted them to be from the countryside, and move to London, where they end up living next to William Blake. And the one bit of English countryside I know best is Dorset. We bought a cottage down there right at the time when I started researching Burning Bright. So I thought, maybe I’ll set it nearby, since I know the area, and then I started getting interested in Piddletrenthide’s history.

Lyme Regis is still very much as it was in Mary Anning’s day—obviously not all the houses and the buildings, though there is a feel about it that’s slightly timeless, and the beaches are definitely the same. When you’re out there you can go fossil hunting and still find the things that she found. That hasn’t changed at all—there are still the landslides and high tides that she would have wrestled with. The structure of the town hasn’t changed because the geography won’t let it. It can’t really spread out that much. It’s down in a valley with quite steep hills around it, and there’s only so much building out you can do. It still has a very small feel to it.

Remarkable Creatures hangs on the unusual friendship between Mary Anning and Elizabeth Philpot. What appealed to you about portraying a close friendship between two women?

I think the best books are about a relationship that changes over time. Somebody described the novel once as normal-change-new normal. People’s lives are measured by their relationships with other people. Maybe because I’m not particularly romantic, I don’t write in general about romantic relationships, although Vermeer’s relationship with Griet was certainly romantic. I’m more interested in the day-to-day relationships that we have. With Mary and Elizabeth it was just so unusual, because Mary was a working-class woman and Elizabeth was a middle-class woman, and that’s a huge difference, then and now too—you know we sort of say everything’s wide open, but honestly are there many people who cross paths? Do we have any working class friends? Not really. So that’s still there, though it’s less rigid, less codified in society now than it was.

Then it was very strict. And also, Elizabeth was 20 years older than Mary, which was unusual. But they were good friends. Lyme Regis was isolated enough that you could get away with unconventional behavior. Also, these women did not marry. They did not have the romantic relationships I would have written about. There’s a bit of it but very little. They had each other and that had to suffice—it more than sufficed, I think. They got on very well, bonded by this love of fossils. I guess I’m interested in more than the romantic template we’ve grown up with. Jane Austen wrote about romantic relationships—also about family relationships and sisters—but really in the end, Elizabeth Bennett ends up with Mr. Darcy and that’s the thing that matters. I thought, that’s all very well in a novel, but in real life that’s not always how it happens. And I wanted to know, what happens to the women who don’t get married? This is what happens to them: they have the sort of friendships that sustain them.

Having lived outside the United States for 25 years, you know how it feels to be out of your natural habitat. This theme appears often in your work. Griet moves into Vermeer’s household, Jem and his family leave Dorset for London, Elizabeth is forced to move to Lyme Regis, where she has little social standing. Do you think you’re drawn to writing about outsiders because of your own life experience?

Yes. There’s drama in having to move. It’s that idea of normal-change-new normal, and the change is often a physical one. There’s such a lot of movement in society; a lot of people don’t stay in their home towns any more. There’s an appealing universality to that. It certainly doesn’t hurt that I’m the other. Although I feel much more comfortable in England than I did at the beginning, I’m still aware of being an outsider. I think that gives me an edge, and I’m happy with it.

You have said, Write about what you’re interested in, rather than what you know. What other advice would you give writers?

Try to make a consistent time when you write every week, rather than just writing when you’re inspired. If I wrote only when I was inspired I’d never finish anything. Finish, finish, finish—you can never judge whether something works until you’ve got the whole thing. Give it to other people to read. You’ve got to find a writers’ group or a class—something that’s going to give you deadlines and a built-in audience. Be open to change: just because it’s typed on your lovely computer it doesn’t mean it’s any good. You have to accept that you don’t know whether something works until you’ve had somebody read it. Find someone whose advice and judgment you trust, and go with that.

What are you working on now?

For the first time I’m setting a novel in the U.S. It’s about an English Quaker woman who emigrates to Ohio in the 1840s and ends up working on the Underground Railroad, helping fugitive slaves escape to Canada. It’s a book about being an outsider, about silence, about freedom – all those big issues. It’s set in a fictional Quaker community just outside of Oberlin, Ohio, where I went to college.

Further links and resources:

- Watch a short video of Tracy Chevalier discussing her latest novel Remarkable Creatures about the fossil-hunting and friendship between Mary Anning and Elizabeth Philpot.