About Heidi Durrow

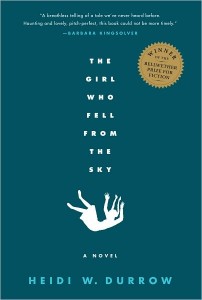

Heidi Durrow and her debut novel, The Girl Who Fell from the Sky, seemed to have been just about everywhere last winter, from the New York Times and Publishers Weekly to NPR’s All Things Considered and The Daily Beast. And the phrases reviewers have used to describe Durrow’s novel represent a kind of wish list for any fiction writer, first-time or otherwise: in The New York Times, Louisa Thomas praised its “vividly realized characters”; in the Dallas Morning News, Karen Thomas wrote of its “hauntingly beautiful prose”; and in the Washington Post, Lisa Page called it “not just a tale of racial ambiguity but a human tragedy.”

The Girl Who Fell from the Sky is the story of Rachel, the daughter of a Danish mother and a black G.I. and the sole survivor of a family tragedy. The book’s warm reception makes it easy to forget that the novel, which won the 2008 Bellwether Prize for best fiction manuscript addressing issues of social justice, was twelve years in the making—a story Durrow had a hard time writing and a hard time publishing. “The writing, editors and agents would say, was great, but there was no market,” admitted Durrow, who, like her protagonist, is biracial:

“No one could relate to a half-black and half-Danish girl. I had a couple of teachers along the way who encouraged me to abandon the project and realize it would never be published. I didn’t listen.”

Then again, Durrow has never been the type to sit back and wait for good fortune to find her. The middle child and only daughter of an African-American enlisted Air Force man and a white Danish woman, she is a graduate of Stanford University, Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, and Yale Law School. In 2007, she launched Mixed Chicks Chat, a weekly podcast on race and society, with Fanshen Cox, an actor, producer and friend. In 2008, the duo created their annual Mixed Roots Film and Literary Festival in Los Angeles, an event that has featured artists such as Angela Nissel, Kip Fulbeck, and Kim Wayans.

Durrow is currently promoting The Girl Who Fell from the Sky around the country, and that tour has provided her with an opportunity to meet up with listeners and festival attendees, as well as readers, who have their own mixed race stories to share. “It is an absolute dream to be able to share this story with a wide audience,” she said. “It’s even more amazing to hear from some readers that it has changed them in some small way. That’s what I’ve always wished to do with my writing.”

This interview took place via a series of e-mails, while Durrow was crisscrossing the country.

Interview

MARY WESTBROOK: I was so moved by the idea of language in the book. Both Rachel and her Danish mother, Nella, struggle to communicate in their adopted cities (Chicago and Portland), and Rachel seems keenly aware of the loss of Danish from her life once she moves to her grandma’s house. There’s also a heart-breaking scene in which Nella uses a slur to refer to her children, and a friend, Laronne, corrects her. Can you talk about the novel’s treatment of language?

HEIDI DURROW: Language is a central part of Rachel’s identity. She has a whole language of words, her mother’s language that is trapped inside her… because there is no one around to speak Danish with any longer. Like Rachel, I grew up speaking Danish. There are simply some words that don’t translate well—which means the story is mistranslated.

Nella struggles with language in a different way. She’s learning new words and doesn’t know how to assign meaning to them. When she unknowingly uses a racial slur to refer to her children, she’s devastated. She knows the powers of language and words. Words—labels specifically—are what we all either embrace or struggle against as we attempt to identify ourselves.

The point of view revolves between several characters. Did you always envision the story told in this way, with this particular group of characters telling the story?

The book began as a third-person recounting—told from Rachel’s perspective—Rachel all grown-up. The problem was I couldn’t figure out what had happened to her beyond her adolescence. I didn’t have a take on what her perspective would be about the fateful day on the rooftop after having gone to college, for instance, or marrying, or falling in love. I knew that the story of the novel would be her growing consciousness of what that accident meant to her. I realized I needed to tell it from her perspective—first-person present tense. Her character warranted an immediacy. The other characters slowly developed when I realized how unreliable Rachel was. She had to be. She was only slowly coming to understand her place in the world.

Heidi Durrow / photo by Frank Stewart

Were certain characters easier to access?

I created Laronne to give Nella an advocate. It was imperative that Nella be humanized in the way a friend could. I created Jamie/Brick because I think every tragedy needs a witness. In life, really, when something bad happens, you need to have someone who says, “Yes, a bad thing has happened.” Roger grew out of a similar need—I wanted the father figure to explain his absence. There are so many missing fathers out there; I can’t explain [why they’re gone]. I gave Roger a chance to explain. And Nella had to have a chance to speak for herself. It was important for the reader to hear about her despair in her own words so that they could—if not forgive—understand what she was trying to do.

While I was reading The Girl Who Fell from the Sky, I couldn’t help but think about the importance of pacing in this novel, of spooling out the right information at the right time. Another writer might have decided to lead up to Rachel’s accident, for instance, but this story seems far more invested in the aftermath of the tragedy.

I originally started the book with the accident, but it didn’t work. The reader needed to care about the characters before there was a tragedy. Because the book is told from different perspectives, I spaced out the information [through the chapters]. This is really how we come to “know” things [in real life]: we put stories together from different sources. Maybe that [impulse] was also a function of being a journalist. You have to back up your story with different sources.

You’ve said that the book took twelve years to write. Can you talk about that process, from the initial inspiration, to the hard work of writing the book?

I started the book in 1997 after reading a newspaper article about a terrible tragedy in which a family perished, but the girl survived. I was haunted by this. I wanted to know—“What would the girl’s survival look like?” I wanted to give her a voice, and a future.

How does a story usually start for you—with a character, with a place?

I start a story with a question. One for which I don’t have an answer. [Even if I don’t] come up with an answer by the end of the story, at least I’ve engaged with the question in a new way. The questions that started The Girl were, “What would the girl’s survival look like?” “How does a girl who loses her family in that way go on to fashion a life for herself?” “How does she learn to love again?” “How does she learn that she is lovable?”

photo by lowjumpingfrog (via flickr cc)

What was the most challenging part of the process for you? The most invigorating?

The most invigorating part of the process was striking upon Rachel’s voice, and finding a way to keep “growing up” her voice. I kept writing and re-writing until it sounded right to me. The most challenging part really was believing in the project. I didn’t listen to the no’s. I took them as information. Kept sending out the writing. Kept revising. And kept true to the vision I had for the book. There were many years where there was just my dogged belief that kept me going. Sometimes that belief waned.

Were you ever tempted to put the book away entirely? What kept you going?

It was the story I had to tell. Beyond the rejections, and also writer’s block that I suffered for a couple of years, I kept going by putting myself on a “regimen.” I sent out my work to everyone. The Poets & Writers’ deadline section was my bible. I posted all the deadlines on my calendar and submitted excerpts from the book to contests, and literary journals, and grants. For every rejection I received for a story, I sent the story out to two more journals. I spent a lot of money on postage, but finally, exponentially, I got some good news.

You share certain biographical details with your protagonist, Rachel. Are you fielding a lot of “Are you Rachel” questions? Do you think readers react differently to you or to the book if they assume the story is based on your life?

I make sure to tell audiences at readings that the accident part of the story is not my story, but inspired by a real story. I can see them all breathe a collective sigh of relief because they’ve been worried about me and want to handle me with kid gloves. I get the “Are you Rachel?” question a lot. And, “Is Grandma your grandma?” “Is Roger your dad?” On and on. I think people ask those questions because 1) they’ve read the book; and 2) they are rooting for Rachel to have grown up okay—maybe even like I did.

When you were interviewed on NPR’s All Things Considered, you were asked whether Rachel’s story reinforced the idea of the “tragic mulatto.” You answered that, for Rachel…

The tragedy is outside of her; it’s not something that’s part of her character. I think that’s something that’s been frustrating about other stories about the ‘tragic mulatto,’ that somehow it was an inherent difficulty within the character. For Rachel… she’s still able to be whole, ultimately, and I think ultimately triumphant.

The question of the “tragic mulatto” was also the topic of the March 3 episode of your Mixed Chicks Chat podcast. The two conversations got me thinking: how did you prepare yourself for interviewers who want to talk about the issues addressed in the story, versus the story? For that matter, do you see the two things—the social issues and the story—as separate? Do you ever feel as if you’re being asked to speak as “the” representative for biracial women?

The question of the “tragic mulatto” was also the topic of the March 3 episode of your Mixed Chicks Chat podcast. The two conversations got me thinking: how did you prepare yourself for interviewers who want to talk about the issues addressed in the story, versus the story? For that matter, do you see the two things—the social issues and the story—as separate? Do you ever feel as if you’re being asked to speak as “the” representative for biracial women?

I won the Bellwether Prize for Literature of Social Change. Of all the awards I could receive, this is the most meaningful, because it means that the book speaks to issues of import to our citizenry. In that way, I don’t mind that when I’m interviewed I am speaking as a representative of biracial women. I’m heartened that people are interested. I do wonder, though, when the book is critiqued as being not enough about the biracial experience. To that criticism I say, “Well, okay, but it’s not a position paper. It’s a story.” As a story it doesn’t provide answers but new questions or new ways of looking at the old ones.

As you’ve promoted the book, what questions have surprised you?

I am most surprised by the generosity of people who share their stories. I have had a number of people “come out” to me, for lack of a better word, about their blended families, or about their grief, or about simply being a young person struggling against the labels, like geek or nerd, that they’d been assigned by peers. I love that they have connected with Rachel despite differences in age, race or culture. They’ve connected their own stories to the stories I’ve told and suddenly feel empowered to talk about it.

poet Remica Bingham

I’ve heard the poet Remica Bingham talk before about the difference between poetry and the “poe-biz”—the difference between writing poetry and getting poetry out into the world. I think most writers have a fantasy about what that the experience of a first book will be like—how did your expectations line up with reality?

There is much you, as a writer, can’t control about your first book, but there were certain things I did to help my book reach the largest possible audience. First, I wrote the best book I possibly could. That seems facile, but I remember the moment I read the final draft on a cross-country flight. At the end I thought, “This is a book.” It was the first time my manuscript felt like a book. I am not bashful about telling everyone about what I have written… whether they can identify with the mixed-race themes, or a coming-of-age story, or whether they even read fiction. Recently I told one guy seated next to me on a flight about the book, and he ordered it that very moment (love in-flight Internet!). That was pretty cool.

You’ve also worked as a journalist and a lawyer. What drew you to those fields, and what draws you to fiction? Do the fields, which seem so different on paper, ever overlap?

I always wanted to be a writer, but I also wanted to be financially secure because I grew up poor. I chose professions that allowed me to write but also would provide me a good, steady paycheck. I was the first person in my family on either side to graduate from a four-year college, and I was driven to make the most of the opportunity. I did practice law, but ultimately, I knew that what I would do best at would be what I loved most, and then I worked to fashion a life as a fiction writer… I am still certain I don’t know how to write a book. I know how to write the book I wrote, but the book I’m writing now is a whole new game. I’m writing and revising and trying to figure it out.

You write across genres. Do you feel more at home in fiction or nonfiction? Do you move back and forth between essays and stories pretty easily?

Fiction is a bit easier. There is more possibility to be poetic. I like lyrical language. I like beautiful sentences. I like the sounds of words next to each other—all of those things are important in fiction in a way that is more heightened, I think, than in nonfiction.

You have embraced technology in a way not all writers have. Can you talk about how or why media like Facebook, Twitter, blogs, and podcasts have made a difference in your writing life?

Writers today are supposed to have a “platform.” You have to have some peeps behind you. Technology has been a great way to connect with people and get some peeps who could support me—and buck me up when my spirits were flagging. I started my blog in 2006 when I was so frustrated by all the rejections that I had received for the manuscript. My blog readers became a great community—and they supported me. It was so reassuring that someone out there cared what I wrote about. Facebook, Twitter, a blog, a Web site—they are all ways to connect with readers—a real genuine connection that isn’t about selling something.

When you are not promoting a new novel, what is your daily life like?

Book tours are not conducive to writing, at least not for me. It’s frustrating because I am inspired by so many of the stories that people share with me and I am desperate to get back to the page. I am a binge writer, although I do write religiously first thing in the morning—three pages written longhand and a sentence of affirmation written ten times in a row. I keep that practice going now on the road, too. It grounds me. Some really wild, raw, good stuff gets written during those times. Other than that I have become a seasonal writer. I write in the fall a great deal, and in January and February. The rest of the year is almost exclusively dedicated to the festival.

Let’s talk about that festival—Mixed Roots, which you and Fanshen Cox created in 2008. How is the festival financed? What makes it different from other festivals?

We have a few festival sponsors: the Japanese American National Museum (JANM), Zerflin Graphic Design. This year Target has stepped in for our Family Event, and we will have a Target Free Family Day at JANM with lots of activities for kids and families centered around issues of identity. We received a generous grant from the Aaronson Fund: Social Justice Works!, and then the rest is donated by family, friends, and podcast listeners. The festival is a fiscally sponsored project of the New York Foundation for the Arts and donations are tax-deductible. Our operation is extremely lean. We have traded on our relationships and done everything we could on our own. I was our website designer until this fall (it’s amazing what you can learn from a library book). Now Grassroots.org has provided us with a volunteer web designer. We staff the festival for the two days with volunteers—friends and family. Festivalgoers know almost my whole family: they are the people ushering, and welcoming people in.

What has been the most surprising aspect of the Mixed Chicks podcast? Do you have a favorite episode? Is there a topic you haven’t addressed yet that you’d like to?

It’s surprising that we constantly have new ideas for the show. You’d think that the whole “mixed thing” could run dry of topics or guests, but we have a backlog of requested shows and guests who we’re trying to fit in. There are so many things we’d still like to address. The best ideas come from our listeners.

The Girl Who Fell from the Sky begins with an epigraph from Nella Larsen’s Passing. You named Rachel’s mother after Larsen, and I’ve heard you call Larsen your muse. What other writers do you turn to for inspiration?

Toni Morrison / photo by Angela Radulescu, via Entheta (Wikimedia Commons)

I love Toni Morrison and Jamaica Kincaid. I love Barbara Kingsolver, and Alice McDermott, and John Edgar Wideman, Russell Banks, Dorothy Allison. And I also turn to poetry when I’m looking for inspiration: William Stafford, Audre Lorde, Sharon Olds, Adrienne Rich. I wish I were a poet.

Do you have any advice for young writers?

Be careful about sharing your writing. I found it was so easy to be shut down by “critiques” in workshops. I read a writer say somewhere that the workshop is “an inherent fault-finding machine.” As a beginning writer, young or old, what you need is someone who can ask you good questions about your work so that you keep writing. My editor, Kathy Pories, did that for me. That’s the main thing. You’ve got to keep writing. Whatever helps you do that—do that.

Extras

- Visit Heidi Durrow’s website and read her blog.

- Hear Heidi and Michele Norris discuss “Reimagining ‘The Tragic Mulatto’” on NPR’s All Things Considered.

- Read an excerpt of The Girl Who Fell from the Sky or hear audio excerpts from the novel.

- See Durrow read in a city near you, or check out this footage from her book tour:

The Girl Who Fell From the Sky: Book Tour from Heidi Durrow on Vimeo.

- Order your copy of The Girl Who Fell from the Sky from Powell’s.

- Read Durrow’s short story “Ethnic Lego Girls Carry Spears” in Smokelong Quarterly.

- Subscribe to Poets & Writers magazine at a special discounted rate for Fiction Writers Review readers.