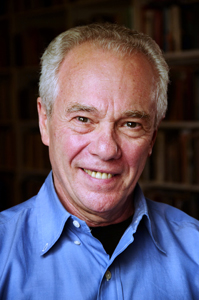

For writers who teach, it’s refreshing to step out of one’s own classroom habits and take a workshop as someone else’s student. I had the opportunity to do just that in June with Bret Lott at the Glen East Workshop, sponsored by Image, on the picturesque campus of Mount Holyoke College in western Massachusetts. I came away with not only the best benefits of a productive fiction workshop, but also with fresh ideas about how to run them—not as logistical projects but as deeply personal ones, in which the teacher is sincere and deeply invested. Because if creative writing teachers aren’t sincere and invested, what good will their workshops be? Workshops are unnatural situations that will always have their moments of discomfort, panic, and even chaos, but creative writing teachers can’t fake their way through them—even teachers as well-decorated as Lott, author of novels such as Jewel, A Song I Knew by Heart, and Ancient Highway, as well as a fine book on the writing craft called Before We Get Started. What struck me more than any craft issue that came up in his workshop was the way Lott took on his students’ writing as an advocate, wanting the muse of story to shine through the page just as much as the students themselves did. The following conversation came about after the Glen Workshop, as I was preparing to move cross-country to a new teaching gig of my own—which made workshopping with Bret Lott perfectly well-timed.

For writers who teach, it’s refreshing to step out of one’s own classroom habits and take a workshop as someone else’s student. I had the opportunity to do just that in June with Bret Lott at the Glen East Workshop, sponsored by Image, on the picturesque campus of Mount Holyoke College in western Massachusetts. I came away with not only the best benefits of a productive fiction workshop, but also with fresh ideas about how to run them—not as logistical projects but as deeply personal ones, in which the teacher is sincere and deeply invested. Because if creative writing teachers aren’t sincere and invested, what good will their workshops be? Workshops are unnatural situations that will always have their moments of discomfort, panic, and even chaos, but creative writing teachers can’t fake their way through them—even teachers as well-decorated as Lott, author of novels such as Jewel, A Song I Knew by Heart, and Ancient Highway, as well as a fine book on the writing craft called Before We Get Started. What struck me more than any craft issue that came up in his workshop was the way Lott took on his students’ writing as an advocate, wanting the muse of story to shine through the page just as much as the students themselves did. The following conversation came about after the Glen Workshop, as I was preparing to move cross-country to a new teaching gig of my own—which made workshopping with Bret Lott perfectly well-timed.

Steven Wingate: Let’s start with the “title question.” What does writing from your own chair mean to you, and how do you get that point across to your students? How can you tell whether they are absorbing what you say?

Bret Lott: This idea—writing from your own chair—comes from my being sometimes a little too exasperated with students who want to be Writers but who don’t yet understand that they already have something To Write. I was in class one day and simply trying to explain yet again that, as Flannery O’Connor wrote, anyone who has lived through his childhood has enough material to last the rest of his life, and seeing the students each sitting in his and her own chairs seemed an apt way to get them to understand that each of them owned a particular point of view and set of experiences, and that those were both held together right that very second in the seat each student was sitting in. That is, you already have a point of view and a story. But so very many writers want to leave that point of view and story—to walk away from themselves—in light of what looks like a better story and point of view held by a writer whose work they admire. They end up wanting to write like somebody else and about somebody else—they want to leave their own chair and go sit in someone else’s chair, a chair that looks oh-so-much-more attractive than their own. The problem with this is that the chair they wish to move into is already occupied, whether by Hemingway, or O’Connor, or Carver, or, or, or—that chair is filled. To sit in that chair would be impossible, because that chair only holds one person—it’s not a love seat. The second idea entailed in this whole analogy or metaphor or whatever the heck it is—hey, I just came up with it one day in class!—is that what made Hemingway’s and O’Connor’s and Carver’s writing important and meaningful and real is that they wrote from their own chair. They didn’t walk away from themselves in order to go sit in someone else’s chair—so what does that say about your own chair? This: It is always and only your chair—no one else’s, just as the chair from which the great writers wrote was their own too. Lesson: Don’t leave you to go find your point of view and your story. You are all you have been given. There is going to be no out-of-chair experience coming your way. This is who you are, and from where you ought and need to write. Whether they’re absorbing it or not? No clue. The proof is in the writing. And undoubtedly the most genuine and real and moving stories I read as a teacher are those that come from real experiences and from the unique point of view through which that experience is rendered. Does this mean one should always and only write about what one has experienced? No. But this whole idea serves as a good starting point for writers.

in this whole analogy or metaphor or whatever the heck it is—hey, I just came up with it one day in class!—is that what made Hemingway’s and O’Connor’s and Carver’s writing important and meaningful and real is that they wrote from their own chair. They didn’t walk away from themselves in order to go sit in someone else’s chair—so what does that say about your own chair? This: It is always and only your chair—no one else’s, just as the chair from which the great writers wrote was their own too. Lesson: Don’t leave you to go find your point of view and your story. You are all you have been given. There is going to be no out-of-chair experience coming your way. This is who you are, and from where you ought and need to write. Whether they’re absorbing it or not? No clue. The proof is in the writing. And undoubtedly the most genuine and real and moving stories I read as a teacher are those that come from real experiences and from the unique point of view through which that experience is rendered. Does this mean one should always and only write about what one has experienced? No. But this whole idea serves as a good starting point for writers.

Writers always get asked about their literary influences, not so much about their teaching influences. You talk in Before We Get Started about John Gardner, whose On Becoming a Novelist is a touchstone for you. Who were some of your other teaching influences, and how have your relationships with them changed over time?

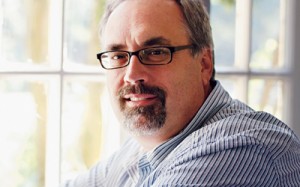

Jay Neugeboren. Image via author site

As regards teachers, Jay Neugeboren was my mentor at UMass Amherst when I was there in the early eighties. He was a very traditional workshop instructor, let everyone say what they thought about the story, guided the conversation, wound things up with his own perceptions—and then let the author walk away and write what he or she had to write. This was exactly what I needed, and how I try to teach to this day. Another influence on me as a teacher was James Baldwin, with whom I had the honor of working at the same time at UMass. I was in a workshop of fifteen students, three from each of the five colleges—UMass, Smith, Amherst, Mt. Holyoke, and Hampshire—that ended up being a very unconventional workshop but important for me all the same: we spent most of the semester talking about literature and art rather than critiquing work.

James Baldwin. Image via Miami Dade College Archives.

I try to incorporate this into my teaching as well, a readiness NOT to be talking always about the work at hand, but about writing at large, and literature, and art. My undergraduate creative writing teacher was John Hermann at Cal State Long Beach, who led off every class by reading a quote about writing from a different important writer, then asking us what we thought. There were many long silences after he asked us, and because he was willing to wait through them for responses, I learned to wait for students to do the same in my own classrooms. Not to mention the importance of quotes from other writers—a cornerstone for the way I teach.

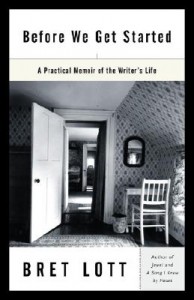

Every creative writing teacher relies on the metaphors, monikers, and catch-phrases that they come up with over the years—the title of this interview being one of your own. At what point did you begin “codifying” some of these? When did you know you were ready to write Before We Get Started?

I taught in the low-residency MFA program at Vermont College for nine years, from 1994 to 2003. Part of our responsibilities were to give lectures to our students —bona fide, real-live lectures. I cannot speak off the cuff very well, and so I always wrote mine out, first word to last. After a few years of this—and publishing a few of them too—I decided to put them together into a book of their own. I’m not a big fan of how-to books, which always seem to offer those willing to pony up the dough a secret way through the genuine hard work writing really is, as though there were a secret tunnel that went through the mountain everyone has to climb in order to learn how to write. Before We Get Started isn’t that sort of book—I think of it more as a who book than a how to. For instance, we faculty at Vermont once got a request from several students to give more lectures on technique—so I wrote and presented at that next residency a lecture called “Against Technique,” this because I think when people begin to ask about technique what they’re really asking is, Can you give me a map to that tunnel through the mountain so I don’t have to spend so much energy climbing this stupid mountain?

I taught in the low-residency MFA program at Vermont College for nine years, from 1994 to 2003. Part of our responsibilities were to give lectures to our students —bona fide, real-live lectures. I cannot speak off the cuff very well, and so I always wrote mine out, first word to last. After a few years of this—and publishing a few of them too—I decided to put them together into a book of their own. I’m not a big fan of how-to books, which always seem to offer those willing to pony up the dough a secret way through the genuine hard work writing really is, as though there were a secret tunnel that went through the mountain everyone has to climb in order to learn how to write. Before We Get Started isn’t that sort of book—I think of it more as a who book than a how to. For instance, we faculty at Vermont once got a request from several students to give more lectures on technique—so I wrote and presented at that next residency a lecture called “Against Technique,” this because I think when people begin to ask about technique what they’re really asking is, Can you give me a map to that tunnel through the mountain so I don’t have to spend so much energy climbing this stupid mountain?

You talked, in our workshop at The Glen, about “reading with a pencil in your hand” and about the side effects of reading so much student work that is either (a) early in the creative process, or (b) significantly misfiring. What’s your relationship to reading, and do you have any advice for younger writer/teachers on how to keep our reading lives vibrant?

I have said on more than a few occasions that when I die, 98% of what I will have read over the course of my life will have been prose that needed work. That’s what I do as a teacher: read stuff in draft for people trying to make it better. As a consequence I end up feeling at a loss when I don’t have a pen in my hand—it’s just a kind of job hazard that the pen is part of the reading life. I read nonfiction now. So far this summer I’ve read Eric Metaxas’s superior biography of Bonhoeffer, Linda Hillenbrand’s Unbroken, and am right now in the middle of Richard Rhodes’s terrific history The Making of the Atomic Bomb. I like facts; I want to know what really happened, this after spending my life writing tales of things that never did. When I’m reading fiction, I’m rereading Patrick O’Brian’s Jack Aubrey-Stephen Maturin volumes—I have read the entire twenty-volume series and am reading them all again. I’m almost through with volume 15 as we speak. But to the question: I keep my reading life as vibrant as I can by reading about what really happened, as I said. And the O’Brian volumes simply and elegantly and convincingly transport me to a different time and place, one light years away from the prose I encounter day in and day out in my fiction workshops. I hope I’m not sounding disdainful about my students’ works: I don’t mean this at all, as I delight in seeing in a student’s work that moment when he or she understands deeply the world the writer is authoring, and seeing in that authenticity a world that delivers back to its author truths that hold water, and that matter, and that the author hadn’t known he or she would encounter to begin with. That’s pure joy, being a part of that.

I have said on more than a few occasions that when I die, 98% of what I will have read over the course of my life will have been prose that needed work. That’s what I do as a teacher: read stuff in draft for people trying to make it better. As a consequence I end up feeling at a loss when I don’t have a pen in my hand—it’s just a kind of job hazard that the pen is part of the reading life. I read nonfiction now. So far this summer I’ve read Eric Metaxas’s superior biography of Bonhoeffer, Linda Hillenbrand’s Unbroken, and am right now in the middle of Richard Rhodes’s terrific history The Making of the Atomic Bomb. I like facts; I want to know what really happened, this after spending my life writing tales of things that never did. When I’m reading fiction, I’m rereading Patrick O’Brian’s Jack Aubrey-Stephen Maturin volumes—I have read the entire twenty-volume series and am reading them all again. I’m almost through with volume 15 as we speak. But to the question: I keep my reading life as vibrant as I can by reading about what really happened, as I said. And the O’Brian volumes simply and elegantly and convincingly transport me to a different time and place, one light years away from the prose I encounter day in and day out in my fiction workshops. I hope I’m not sounding disdainful about my students’ works: I don’t mean this at all, as I delight in seeing in a student’s work that moment when he or she understands deeply the world the writer is authoring, and seeing in that authenticity a world that delivers back to its author truths that hold water, and that matter, and that the author hadn’t known he or she would encounter to begin with. That’s pure joy, being a part of that.

Another one of your phrases that stuck with me was “surrendering the self to the work”—serving the art rather than asking the art to serve the writer. You also talk about this in Before We Get Started, particularly the essay “Against Technique.” How can you tell if your students are making that surrender, and how do you guide them into it? What do you do with students who don’t take that bait?

Generally I can tell when the story is surprising me with the connections it’s making. Am I reading something that releases within a string of plausible, believable, well-crafted sentences and scenes (the easy part) a series of surprises that connect themselves deeply to the story it is trying to create (the hard—and rewarding—part)? When I feel, while I am reading a story, that story’s connection to itself and the attendant surprises I the reader am encountering—this increasing series of recognitions I didn’t know was there but which are now happening—I’m pretty certain the writer has stumbled into some truth he or she wasn’t aware of but which is being discovered as the author is going along. If a story, however, isn’t releasing any of these surprises—no matter how plausible, believable, and well-crafted the sentences and scenes are—if it’s predictable, even if surprising in the plot sense, then the author isn’t moving into that unknown territory of himself. Guiding a student along is always, it seems to me, an absolutely boots-on-the-ground time that happens within the workshop—there is no real way to guide someone into understanding these things without there being something concrete he or she has created upon which or with which to play out this whole dynamic between the author and what he has created. I hope I’m making sense here. Students who don’t take the bait (not sure I really like that term, as though the bait—this idea of self-discovery—were false) don’t take the bait. You can lead a horse to water, but if the horse believes he knows better than you do, then, well . . .

After many years teaching at the College of Charleston, you moved to Louisiana State University and became editor of The Southern Review, which is regarded as a peach of a job. Why did you go back to teaching, and are you still glad you made the transition?

I don’t like rejecting the work of writers. Teaching is all about hope—about possibility, about what can be. It’s definitely NOT about Yes, You Too Can Be A Writer! But it is about possibility. An editor’s job—that of selecting what will be included and what won’t—is, finally, all about No. I don’t want to live there.

You’ve been teaching creative writing since 1986. How has its pedagogy changed, what are its big influences now, and where do you see it going?

You’ve been teaching creative writing since 1986. How has its pedagogy changed, what are its big influences now, and where do you see it going?

I really can’t see that anything has changed. A student writes something, puts it up for public criticism, and gets it criticized. Same as when O’Connor and Carver put their work up in workshops. Same as I did, too, and same as my students do to this day. O’Connor wrote that all criticism is inherently negative—and that’s what this whole workshop thing is about. I don’t think that’s going to change. What matters is the care and tact and respect with which one approaches this truth.

Imagine you have three bits of advice to give a writer who is just about to embark on a career of teaching creative writing. What would they be?

- Make and observe your own time to write your own work.

- Compartmentalize your time—This is my writing time, and now this is my teaching time.

- Make sure your students understand there is no secret to this at all. That writing is something you are practicing right alongside them, that your issues are their issues, that there are no secrets, there have been no major breakthroughs of esoteric information regarding the telling of stories, that “What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun.” And they need to understand the liberating fact this can be: what makes the story they are telling different is that it is their story to tell, and no one else’s.

Further Links and Resources:

- Read Lott’s creative non-fiction essay “Genesis,” from Before We Get Started, in Brevity

- Read Lott’s essay “Against Technique“

- See Bret Lott read from his novel Ancient Highways: