I first became aware of the insinuating power of the Italian writer Antonio Tabucchi through his short volume of dream stories, Dreams of Dreams (translated by Naney J. Peters). In this book Tabucchi presumes, as only a masterly writer can, to peer in on a core, transformative dream dreamt by various writers, musicians, and artists: Ovid, Villon, Goya, Stevenson, Debussy, Lorca, Chekhov, and so on. Each story is like an x-ray into the secrets of the creative process.

My favorite among these stories belongs to the dream of Fernando Pessoa. The great Portuguese poet’s artistic achievement was one of Tabucchi’s admiring obsessions, and mine too: Pessoa created a series of alternate personalities through which he wrote poetry, and in the process undermining any reader’s complacency about the nature of a singular “self.” These interior “heteronyms” had names—Alberto Caiero, Álvaro de Campos, Ricardo Reis, and Bernardo Soares—and each wrote a distinct type of poetry. They formed Pessoa’s own literary salon, imaginary writers who admired, criticized, and competed with each other.

In the story “Dream of Fernando Pessoa, Poet and Pretender,” Pessoa’s dream takes place during the night of March 7, 1914. The next morning Pessoa will commit the first of his heteronyms, Alberto Caiero, to paper, in a burst of three days’ inspiration that will become the book The Guardian of Sheep.

Pessoa travels in his dream by mysterious carriage to a whitewashed house, where he suddenly transforms back into a child and meets Caiero for the first time. Their conversation generates the remainder of Pessoa’s literary and personal life:

I am the deepest side of you, said Caiero, your dark side. In this I am your master.

From the bell tower in the neighboring village the hour struck.

And what should I do? asked Pessoa.

You must follow my voice, said Caiero. You will listen to me in waking and in sleep. Sometimes I’ll disturb you, and sometimes you won’t want to hear me. But you must listen to me, you must have the courage to listen to this voice if you want to be a great poet.

I’ll do it, said Pessoa. I promise you.

He rose and took his leave. The carriage was waiting for him at the door. Now he had become an adult again, and his mustache had grown back. Where should I take you? asked the driver. Take me toward the end of the dream, said Pessoa, today is the triumphant day of my life.

All the stories in this collection vibrate with the elemental, eerie power of change, as in the dream that becomes a nightmare by the Latin poet Ovid, soon after his exile to the Black Sea by the emperor Augustus. In the dream Ovid transforms into “an enormous butterfly, as big as a man, with majestic yellow and blue wings. And his eyes, the immense spherical eyes of a butterfly, embraced the whole horizon.”

But when Ovid tries to recite his poetry before the emperor, his voice “was only the hiss of an insect.” Enraged, the emperor commands that his wings be sliced off by the guards, and the shorn butterfly that is Ovid is escorted from the palace grounds. Soon he will wake and discover himself once again far from his beloved Rome.

Fernando Pessoa’s engagement with multiple identities was a great influence on Tabucchi, who was interested in how those often unspoken internal selves transform experience into art. In the title story of Tabucchi’s The Flying Creatures of Fra Angelico (translated by Tim Parks), the main character is the Dominican friar and early Renaissance painter Fra Angelico (known during his lifetime as Fra Giovanni), who believed that his paintings were divinely inspired. Tabucchi imagines one of those moments of inspiration when Giovanni, while collecting onions in the monastery garden, is visited by a birdlike creature.

“Was it you who called me?”

The bird shook his head and, pointing a claw like an index finger toward him, wagged it.

“Me?” asked Fra Giovanni, amazed.

The bird nodded.

“It was me calling me?” repeated Fra Giovanni.

After Giovanni’s counter-intuitive revelation, we realize that he is emotionally enmeshed with this creature—it is an interior presence and yet somehow outside him, a presence that, we later learn, only he can see.

The creature is soon joined by two others, which have their own particular identities. One, shaped like a dragonfly, bears a face that resembles Nerina, a young woman Giovanni once loved before be became a friar. The third is a little winged half-creature with a tail, and when the three are united before Giovanni, the dragonfly resembling Nerina says, “Tomorrow you must paint us, that’s why we came.”

And he does, adding these strange creatures to the series of frescoes he has been painting in the alcoves of the monastery, so that others can finally see the vision that until then belonged only to him.

The restless energy of transformation in this story collection possesses a power that even an immortal longs for. In the story “Letter from Calypso, a nymph, to Odysseus, King of Ithaca,” Calypso imagines Odysseus as an old man: “you live in change. Your hands have become bony, with protruding knuckles; the firm blue veins that ran across them have come to resemble the knotty rigging of your ship.” The many years since his departure from her island have passed as if nothing, and Calypso envies Odysseus his old age, left alone as she is and weary of her own “white, unchanging hands” and “the empty terror of eternity.”

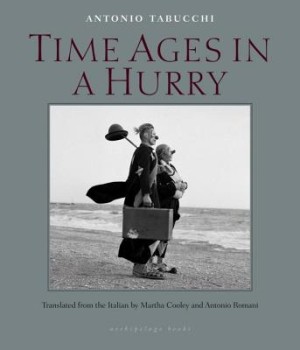

I think that Calypso might envy every character in the most recently published collection of Tabucchi’s fiction, Time Ages in a Hurry (translated by Martha Cooley and Antonio Romani), published in April by Archipelago Books. They struggle with the hauntings of memory and time’s pitiless erosion of the past. Yet they somehow manage to wrestle a little grace into their lives because the imagination—what Tabucchi would call “the deepest side”—can be “stronger than reality.”

And the range of characters in search of grace is extremely varied. In “Clouds,” a young girl—born in Peru and adopted by Italian parents—befriends an old man—a jaded, former soldier—at the beach, and together they interpret the shapes of clouds in the sky, in ways that reflect their separate and complicated pasts. In “Festival” a man recounts a tale of a documentary filmmaker who, though he had no film in his camera, managed to play the role of a witness and make a dent in the political show trials in Cold War-era Poland. In “Against Time,” a man on a plane to Crete pages through the weekend magazine of a newspaper casually offered by a flight attendant; he finds himself so drawn into a series of photos depicting the horrors of the past century that, upon landing, he prepares to change the course of his life.

And the range of characters in search of grace is extremely varied. In “Clouds,” a young girl—born in Peru and adopted by Italian parents—befriends an old man—a jaded, former soldier—at the beach, and together they interpret the shapes of clouds in the sky, in ways that reflect their separate and complicated pasts. In “Festival” a man recounts a tale of a documentary filmmaker who, though he had no film in his camera, managed to play the role of a witness and make a dent in the political show trials in Cold War-era Poland. In “Against Time,” a man on a plane to Crete pages through the weekend magazine of a newspaper casually offered by a flight attendant; he finds himself so drawn into a series of photos depicting the horrors of the past century that, upon landing, he prepares to change the course of his life.

History, personal or collective, weighs on everyone in these stories, sculpting their inner lives. And yet, Tabucchi suggests, an unlikely transcendence is possible. In “The Circle,” one of the strongest stories in this collection, a childless woman who is nearing the edge of her fertile years leaves a large Swiss family gathering, for “some air.” She heads for a nearby plateau above Geneva, a quiet place she and her husband had visited years ago when they were engaged. There, she finds herself sharing the wide plain with a distant herd of wild horses.

In curiosity they gallop toward her, and she awaits their arrival in terror. But at their close approach they begin a racing circle around her, “like a crazy whirling merry-go-round with broken brakes,” and she can only watch, transfixed.

The horses were circling, ever faster, fast like her thoughts gone circular, a thought that thought itself, she was aware only of thinking she was thinking, nothing more, and in that moment the leader of the herd, in the same sudden way he’d drawn the circle, now broke it, and with an unexpected swerve that seemed to defy the laws of nature, he slanted off dragging the whole herd behind him, and the horses galloped away.

The horses leave, but not her vision of their circling. She sits down on the grass stubble, stunned. Something of this strange encounter refuses to escape, something that, the reader intuits, she will have to continue interpreting and reinterpreting, searching for its significance in the rest of her life. As the sun begins to set she takes that first imaginative step and can’t help seeing that “the orange light already held hints of indigo, the horizon was circular, it was the only thing she was able to think, that the horizon was circular, it was as though the circle drawn by the horses had expanded to infinity, transmuting into the horizon.”

Antonio Tabucchi, born in Pisa, Italy in 1943, was the author of dozens of works of fiction, in a career that spanned over 35 years. The winner of several international awards, and often considered a candidate for the Nobel Prize, Tabucchi is best known in English for his short stories and the novel Pereira Maintains. A longtime lover of Portuguese culture, he died in Lisbon in 2012.