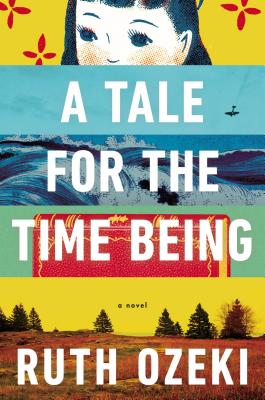

Early in Ruth Ozeki’s new novel, A Tale for the Time Being (Viking), a writer with whom Ozeki shares her first name finds a Hello Kitty lunchbox on the beach of her Pacific-Northwest island. The lunchbox contains a watch, a French composition book, a set of letters in Japanese, and, most intriguingly, the diary of a sixteen-year-old Japanese girl, Nao Yasutani. As the novel alternates between excerpts of Nao’s diary and third-person point of view sections in which Ruth reacts to the diary and the other documents, A Tale proves an ambitious, if ultimately frustrating, meditation on suicide, the reader-writer relationship, and the human experience of time.

Though Ozeki has rather evenly divided the narrative space of the novel between Nao and Ruth, the book’s center of gravity is unquestionably Nao (pronounced “now”). At the start of the novel, Nao promises to tell the story of her hundred-and-four-year-old great-grandmother Old Jiko, but instead she recounts her own story, her family’s move from Sunnyvale, California, back to Japan, the bullying she suffers at her new school, her father’s suicide attempts, and the evolution of her own suicidal thoughts. Similarly, Ruth really ought to return to her long languishing memoir, but instead she spends her time researching Nao and her family. Ruth’s compulsion to study Nao and her fascination with the young woman’s life will not be mysteries to the reader; Nao is easy to root for even when we know she’s misinterpreting or behaving badly. She is the novel’s most nuanced and fully imagined character, at once recognizably adolescent and highly specific: observant and funny, angry and occasionally violent. And big questions propel Nao’s narrative: Will her father succeed in his next suicide attempt? Will Nao attempt suicide, too?

In both the Nao and Ruth portions of the novel, characters grapple with the book’s themes explicitly. They talk and write and think about how they are experiencing time, about what it means to write the story of your life or to commit suicide. Nao seeks to live in the “now.” As she recounts her past, she wonders not only who will read her story, but also when she will catch up to her present and what catching up will feel like. At the same time, she seems to believe that “now” is an impossibility:

In the time it takes to say now, now is already over. It’s already then. Then is the opposite of now. So saying now obliterates its meaning, turning it into exactly what it isn’t. It’s like the word is committing suicide or something.

Because Nao is sixteen and so often so likeable, I felt a good deal of sympathy, if occasional impatience, watching her think through the novel’s big ideas. When her father and great-uncle chew over those same ideas, they do so in essays and letters that offer rare windows into their perspectives. We have thus far seen them only from a distance, so it’s thrilling, for example, to read Nao’s father’s thoughts on suicide:

Suicide stops life in time, so we can grasp what shape it is and feel it is real, at least for just a moment. It is trying to make some real solid thing from the flow of life that is always changing.

But Ozeki prioritizes the novel’s thematic explorations at the expense of its other potential pleasures. At the end of Nao’s first diary entry, the girl invites her imagined reader to count the moments with her, really, to be in time with her. Ruth accepts this invitation and decides to read the diary at roughly the same rate at which the girl wrote it, reasoning that this will help Ruth to “more closely replicate Nao’s experience.” And Ozeki’s novel seems to invite us to be in time with Ruth as Ruth is in time with Nao. But up until the novel’s final movements, in which Ozeki suggests that Ruth has an almost magical relationship to the diary, Ozeki doesn’t seem to know how to render this deliberately slow reading process in a fashion at once gripping and organic. She saddles Ruth with a series of logistical tasks and artificial hesitations that serve little purpose other than to slow the progress of the book: Ruth is implausibly reluctant to read the diary at the start, and once she is reading the diary in earnest, she takes far too long to come to obvious realizations about it; she spends a good deal of time typing queries into search engines and waiting for results to arrive over her slow Internet connection; and in many other scenes, she listens to her husband, Oliver, lecture on ocean currents and quantum physics. Whenever Oliver shows up, paragraphs of time-passing exposition or explanation are soon to come. Further, his didacticism demands that Ruth first fumble and then play student. Given that Ozeki has designed the novel’s puzzles, that Ruth—whom we’re encouraged to read as her proxy—should appear so helpless before those same puzzles rings false.

It’s true that by forcing the reader to encounter Ruth’s life nearly moment-by-moment Ozeki succeeds in manipulating the reader’s experience of time and in drawing attention to the novel’s architecture, to the reader’s sense of urgency and concern for a character whose fate she cannot change. But the result of all Ruth’s waiting and listening, all her implausible reluctance, is that, even as she does things, she feels more like a recording device than an independent agent. (To be fair, Ozeki is clearly interested in exploring the role of the writer through her depiction of Ruth, in asking whether the writer should be a mere observer or whether that position is even possible.) Moreover, the characters who surround her are so thoroughly cardboard, so clearly mouthpieces for Ozeki’s research, that Ruth starts to feel cardboard too. Even as I spend time with her I am never in time with her. Except, obviously, as we both read Nao’s diary.

Ironically, or perhaps fittingly, Ozeki’s writing is strongest at its greatest remove from the present moment. She seems at home in Nao and her father’s voices and especially in the voice of Nao’s great-uncle Haruki #1, a World War II kamikaze pilot. Indeed, in Ruth and Nao’s paired readings of Haruki #1’s letters and journal, Ozeki most movingly aligns the novel’s thematic and emotional interests. Haruki’s #1’s many-decades-old writing on the eve of his death influences virtually every character in the novel and changes their attitudes toward one another and toward suicide. The letters and journal also brought me to tears. I was, in those few moments, really with Nao, with her father, with Haruki #1. Without discounting the real and compelling reasons to mediate Nao’s experience through Ruth, the emotional impact of the other narratives is the novel’s best argument for fiction’s power to manipulate time, to make the past feel present, to make the reader live in the moment with a character.

- For more on Ruth Ozeki’s work, upcoming appearances, or to follow her on her blog, please visit the author’s Website.

- Read Felicia R. Lee’s March 12th profile of Ozeki in the New York Times.

- You can also check out Anita Sethi’s March 7th interview with Ozeki for the Guardian.