Gabriel de Boya finds himself in Bolivia on the eve of the historic 2004 election, just as Evo Morales takes the lead and looks to be the nation’s first indigenous president. Though he’s half-Russian and half-Chilean, the son of a leftist academic, and now working for an unscrupulous hedge fund, Gabriel de Boya is first and foremost a confused twenty-something American far away from home.

Gabriel de Boya finds himself in Bolivia on the eve of the historic 2004 election, just as Evo Morales takes the lead and looks to be the nation’s first indigenous president. Though he’s half-Russian and half-Chilean, the son of a leftist academic, and now working for an unscrupulous hedge fund, Gabriel de Boya is first and foremost a confused twenty-something American far away from home.

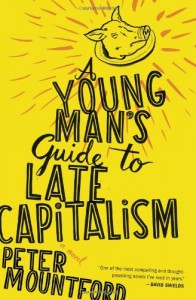

As Peter Mountford‘s debut novel, A Young Man’s Guide to Late Capitalism (Mariner, 2011), revs up, Gabriel gets himself into a series of pickles. The character’s front as a freelance reporter begins to crumble. He breaks off an affair with a cunning Wall Street Journal correspondent. His hedge-fund employers demand details of the impending natural resource nationalizations. Gabriel falls in love with Evo’s beautiful press liaison. He gets too close to the action during one of the daily strikes. A foursome of women, all stronger and smarter than him—his mother, his boss, his girlfriend, and his ex—draw and quarter Gabriel’s psyche as he weighs good lies against bad ones, victimless crimes against prosecutable ones.

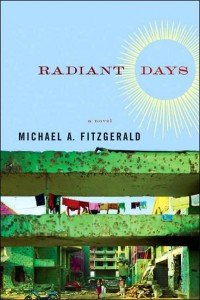

This is not your grandfather’s expat novel. It feels like part of a new wave in that old tradition, along with Michael Fitzgerald’s Radiant Days and Clay Morgan’s Santiago and the Drinking Party. You won’t find young loners driven by the vague forces of alienation or boredom, in search of exotic meaning. Gabriel is instead driven by a brand of greed as nuanced as it is misinformed. He doesn’t see making the world a better place and making a shitload of money as mutually exclusive; he thinks they could happen in the same day, with the same opportunistic half-truth.

This is not your grandfather’s expat novel. It feels like part of a new wave in that old tradition, along with Michael Fitzgerald’s Radiant Days and Clay Morgan’s Santiago and the Drinking Party. You won’t find young loners driven by the vague forces of alienation or boredom, in search of exotic meaning. Gabriel is instead driven by a brand of greed as nuanced as it is misinformed. He doesn’t see making the world a better place and making a shitload of money as mutually exclusive; he thinks they could happen in the same day, with the same opportunistic half-truth.

The novel never navel-gazes but instead drops the protagonist right into the crucible of our life and times. Among other things, the book is a crash course on Latin American history, contemporary economics, and international politics—with a page-turning plot. Its characters treat their careers with all the gravity they would in real life; Mountford is capable of the kind of sublime insights about work and human nature that we’ve stopped expecting from our novelists.

A Young Man’s Guide to Late Capitalism does a better job than Forbes at covering the whims of high finance, and the novel does so without a trace of easy morality. You won’t find any heartless Gordon Geckos in here, swinging moneybags or fat cigars.

A Young Man’s Guide to Late Capitalism does a better job than Forbes at covering the whims of high finance, and the novel does so without a trace of easy morality. You won’t find any heartless Gordon Geckos in here, swinging moneybags or fat cigars.

Gabriel does not always act honorably. At times, he’ll make you cringe—but his flaws are the flaws of his age. He is an imperfect man-boy who understands that, for his generation, jobs and bank accounts often outlast relationships.

It’s amazing how astutely Mountford renders the nature of money. He shows its most surreal qualities: its ability to expand or contract based on obscure tidbits of information that need not be true so much as believable. But he also captures its cold realism: the fact that unfortunately—perhaps tragically—it can be a force greater than love, greater even than family.

This is quite simply one of the smartest and most readable debuts I’ve come across in years. Mountford is a writer who rolls up his sleeves and digs into the zeitgeist all the way up to his elbows. He’s fearless in his depiction of world leaders, global events, and the oft-ignored gray areas between morality and success.