What exactly is innovative fiction? Sarah Falkner answers this question with a wickedly deft disregard of the rules of craft and narrative structure followed by most works of contemporary fiction. Animal Sanctuary, Falkner’s first novel and winner of the seventh Starcherone Prize for Innovative Fiction, is a profound and meticulously constructed story about the lives of artists who are both nurtured and devoured by their art forms. Each of the characters occupies a specific place in the hierarchy of the art world, whether an actor, as is the “has-been” Kitty Dawson, or a performance artist, as is the actor’s son, Rory. Each of the characters shares some part of the public’s attention and, consequently, a share of power. And each seems unaware of coming by that power at the expense of another artist whose work spares the rising star the serious, often physical, dangers that may come with performance and criticism.

What exactly is innovative fiction? Sarah Falkner answers this question with a wickedly deft disregard of the rules of craft and narrative structure followed by most works of contemporary fiction. Animal Sanctuary, Falkner’s first novel and winner of the seventh Starcherone Prize for Innovative Fiction, is a profound and meticulously constructed story about the lives of artists who are both nurtured and devoured by their art forms. Each of the characters occupies a specific place in the hierarchy of the art world, whether an actor, as is the “has-been” Kitty Dawson, or a performance artist, as is the actor’s son, Rory. Each of the characters shares some part of the public’s attention and, consequently, a share of power. And each seems unaware of coming by that power at the expense of another artist whose work spares the rising star the serious, often physical, dangers that may come with performance and criticism.

The most consistent plot-line in this complex, unconventional novel relates to an animal sanctuary, started by accident as an extravagance to please Kitty’s fetishes and insecurities, but which grows both in size and relevance as the novel progresses. It is where Rory’s artistic ideas first take seed and where Kitty finds her calling and heritage. More importantly, it provides sanctuary not just to abandoned circus animals but also to artists just as talented as Kitty and Rory, who have no hope for success beyond the role of “makers” without patronage or media attention. Those employed at the sanctuary are effectively human animals through whom the more privileged artists orchestrate their complex performances.

Rory’s evolution as an artist comes at some risk; he first courts, then shows disrespect to, a mentor whose rich acquaintances disgust Rory. Yet, later in life, when Rory is a successful artist petitioning the government for a grant, he allows his assistant, Nora, to do most of the work. In Nora’s words:

“[O]n certain levels [Rory] tries to be the best he can… he’s aware of inequity in the art world, he tries to address it in the ways it has occurred to him, but he makes a common error in thinking that since as a gay man he can be considered a member of a group that has been oppressed, he has some sort of exemption from ever being considered oppressive himself.”

Nora’s story forms the crux of the symbiotic relationship between the makers of art and those who represent it. Seamlessly woven in with her self-doubt is Rory’s almost didactic narrative of the grant application. He expresses his ambivalence about having benefited from as well as being held back by his mother’s fame, but also relies on Nora to complete the pesky grant narrative for him. Rory’s fame shields him from the injustices of art world, but it also keeps him from personally connecting with the people who might help develop his art.

Art patronage is represented in various forms, but the complexity of the artist/patron relationship is especially evident in the character of the misogynist film director, Albert Wickwood, whose resentment for his mother (and all mothers) is emphasized throughout the novel. He is behind Kitty’s rise to success, but, ironically, he is also the director who ends her career. Wickwood’s art is controversial in both method and form. He wants to draw attention to animal cruelty, but he’s often insensitive to the conflicting messages he conveys.

For example, in a fragment about one of Wickwood’s documentaries, we see that he often fails to observe the realities of his subjects in blatant and disconcerting ways. In this particular narrative, “one of the dolphins breaks away from the group repeatedly in order to linger against the frothing jet of the water intake…” while an oblivious voice-over exclaims: “’They’re a mighty playful bunch, aren’t they?’” Meanwhile, in italics, the stunt-woman observes: “One of the dolphin attempts to insert his penis in the soft tissue at the rear of the turtle’s shell would be prominently visible from the first camera position.” We then shift back to the official version: “From this new panel, the lone dolphin and the turtle pair is mostly eclipsed….” The dolphin’s playful nature is juxtaposed with a disturbing subtext and significant omissions.

Thus, relationships between artist and art object, mentor and mentee, patron and protégé, are explored in double-edged turns through these characters’ lives. Wickwood is near-sadistic in his direction, effectively treating his actors as animals (“Kitty Dawson responded best to some of the methods trainers used with dogs,” Wickwood confesses during an interview). Similarly, Rory’s indifference to Nora’s struggle suggests that patronage comes with some inevitable oppression. In Animal Sanctuary, art demands blood sacrifice, and injustice comes dressed in the garb of good intentions. Success is relative, and art, like nature, is both a mother and a killer. The titular animals in their sanctuary are also unemployed artists, refugees, victims of rape and violence; proud, even elegant, but nonetheless, displaced tigers and lions.

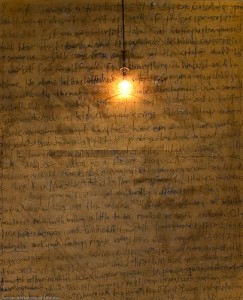

But to reduce the book to these dichotomies would be a disservice. Animal Sanctuary doesn’t raise a political platform. Rather, it resonates with moral questions about the role of art in social change through fragments in various narrative forms: film synopses, a textbook passage on film theory, an interview fawning over the director’s success juxtaposed with another focused on Wickwood’s best actress, Kitty, and whose tone leans toward sexist brow-beating. Falkner braids her narrative with emails, journal entries, letters, magazine articles, blogs, and even voice recordings. These are interspersed with the most intimate thoughts of the characters, some of whom make dramatic entrances only to disappear, never mentioned again.

But to reduce the book to these dichotomies would be a disservice. Animal Sanctuary doesn’t raise a political platform. Rather, it resonates with moral questions about the role of art in social change through fragments in various narrative forms: film synopses, a textbook passage on film theory, an interview fawning over the director’s success juxtaposed with another focused on Wickwood’s best actress, Kitty, and whose tone leans toward sexist brow-beating. Falkner braids her narrative with emails, journal entries, letters, magazine articles, blogs, and even voice recordings. These are interspersed with the most intimate thoughts of the characters, some of whom make dramatic entrances only to disappear, never mentioned again.

Trying to encapsulate the complex animal refugee metaphor brings to mind a quote from Wickwood:

“Now, I don’t really ever enjoy discussing beforehand with anybody else just how it is I intend to pull of one of my stories. It always seems to come down to trying to describe in words how I am going to show something visual by not-showing it: a perverse impossible task of the type gods or devils set before an unlucky soul.”

Wickwood holds that plot “is absurd on paper,” and a work of art ultimately “succeed[s] precisely because the plot eventually steps aside and lets other things be accomplished.” Thus, Falkner, by discarding plot and structure conventions, highlights the ambivalent systems which both nourish and threaten art. The book contains no climax, no resolution, no punchy dialogue, no riveting main scenes. Nor does it contain any real protagonists or antagonists. The characters, like their art forms, are submerged within murky, subconscious waters, and only the lights of the camera reveal their true natures.

Sarah Falkner

Even beyond the novel’s halfway point, the reader may still be uncertain of the story’s protagonists or the animal sanctuary’s role. But the pages keep turning because of Falkner’s incisive prose, her accurate and fluid discussion of the aesthetic values of film, and the moral complexity of her characters. The reader is left, at the end, with the singular effect of a well-executed work of art full of dark undercurrents, sometimes destructive, sometimes spiritually uplifting. In Animal Sanctuary, Falkner breaks the modes of craft to show us that the idea of control over art is an illusion. The creation of art can be controlled no more than its interpretation, and no more than the change, violent or passive, it may excite among generations of its audience.

Further Links and Resources:

Read a Q&A with Sarah Falkner at the blog, We Who Are About To Die.

Browse through images from the innovative art book project, City of Salt, for which Falkner collaborated with visual artists Nicholas Kahn and Richard Selesnick.