Serial killers make for curious metaphors in literature. If contemporary writers are all beneficiaries of Chekhov’s loaded gun, you sort of expect a fictional serial killer to, well, show up and kill people. Such characters are introduced so they may wreak consequences. Flannery O’Connor’s Misfit springs to mind as the kind of indelible force whose streak of (un)Godly offings haunt lonely Georgia highways before rolling off the page and into legend.

Serial killers make for curious metaphors in literature. If contemporary writers are all beneficiaries of Chekhov’s loaded gun, you sort of expect a fictional serial killer to, well, show up and kill people. Such characters are introduced so they may wreak consequences. Flannery O’Connor’s Misfit springs to mind as the kind of indelible force whose streak of (un)Godly offings haunt lonely Georgia highways before rolling off the page and into legend.

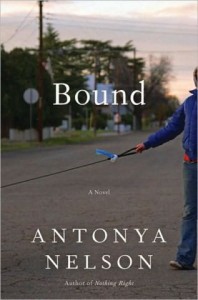

In Antonya Nelson’s newest novel, Bound (Bloomsbury USA, 2010), we learn of another infamously monikered killer. This one calls himself BTK (Blind, Torture, Kill), and he operates in Kansas, no less—home to mythical flying cows. So, ammunition ready. We are expecting shots fired. As the novel states early on: “There would always be bad guys; evil was one of the rules.”

But for married couple Catherine and Oliver Desplaines, the crime scene is a more subtle domestic one; the violence, emotional rather than physical, not even always perceptible, and the ties that bind are of the memory-lane variety. Into this household enters young Cattie, the daughter of Catherine’s former high school friend Misty, who dies in a car crash in the book’s opening chapter.

photo credit: Marion Ettlinger / photo from vermontstudiocenter.org

The BTK exists on the margins of their lives as an ominous threat, but his presence does not inspire fear in any of the characters, who have been following his notorious acts for decades. In this way the BTK goes from character to signifier. He lurks throughout the narrative as a kind of jumping off point. A conversation starter. A trigger to one’s past. The plot points of a map on a driving tour of victims’ houses.

So, then, taken as a metaphor, what, does it mean to be bound? Surprisingly, the connotations are much softer than you’d expect:

It was not legally binding. The expression itself interested Catherine. Legally. Binding.

One trademark of the serial killer’s methods was binding. Drawstrings, extension cords, scarves, panty hose—whatever, it seemed was at hand. Catherine lay in bed letting her thoughts circle and knot (neckties, jump ropes, leashes…) while Oliver prepared for his work day.

Here, and later, it is the thoughts, not the killer, doing the twisting, and this image repeats: “For Catherine, Wichita was a big bag of loose yarn, ensnared connections that knotted together the past and the present without clear cause and effect or pattern. Cattie couldn’t make sense of it yet, but she was good at listening, patient at untangling.”

And later still: “Cattie had begun braiding together the city as Catherine recalled it, one curious strand at a time, today aided by the icy blur the windshield view provided her.”

In the absence of horror flick-esque plot twists, then, what makes Bound eminently readable are Nelson’s powerful characterizations. Catherine and Oliver and those surrounding them are all interestingly flawed but not unlikable. The point of view shifts with each chapter, allowing intimate observations from more than one perspective, and, as a result, it is hard to say exactly whose story Bound is. Usually it is the same character’s vantage point for the duration of a chapter, but sometimes this changes with an authorial sleight of hand. Suddenly and smoothly, the reader is in someone else’s head, and the transition is always a physical shift (eye contact in a mirror, or the phone conversation hangs with up with someone different than who dialed).

The structure of the story is seamless—four sections, each named for a season. The internal rhythms are equally consistent: the prose clean, crisp; longish paragraphs, a layered description of clause upon clause—and then the variance with shorter lines to round it out:

Houston was not at all what Catherine had expected, although she couldn’t quite pin down what she had expected. Astronauts? Oil rigs? Ten-gallon hats? It was moist, filled with trees, houses that reminded her of ones in Wichita. When she’d arrived, she’d parked in Misty Mueller’s bungalow driveway and studied the front porch. Yellow brick, cream-colored trim, a flower bed and porch swing. Frogs, crickets, birds: the rhythmic noise of creatures and nature, the atmosphere pleasantly sodden.

Antonya Nelson’s landscapes (something else we are often bound to) are noteworthy for the beauty she finds in the boring. Kansas. Colorado. Vermont. Houston, briefly, but this is not a big-city narrative. Rather, it seems to be exploring the unsettling mysteries that swirl around seemingly quiet outposts, a topographical subconscious. Here, the book seems to say, this small town, this personal history: Rocks left unturned.

Bound is also about seasons (can you be bound to the seasons?)—seasons of life as one ages, and how seasonal shifts affect the mood of a landscape, interior and exterior:

There had been an ice storm in Kansas, a snow that turned to rain, then back to snow, and then, whimsically, finally, to sleet…Overhead, the trees were laden. They creaked ominously. Eventually, when the sun emerged, everything began to snap. All over town the branches crashed down—on cars, on houses on power lines. Giant boughs. Devastating breaks. The streets were filled with broken limbs, electricity went out, wind-shields were shattered. What remained was a forest of strange topless trees, their severed appendages imploring the sky. Everyone stayed at home, built fires, used flashlights, listened to the radio.

What makes this scene particularly interesting is the tension between exterior and interior landscapes. The characters are all happy to take a snow day as the trees self-destruct around them. Contradictions such as this pop up throughout Bound. In the case of young Cattie, the death of her mother gives way to unexpectedly forged connections with Catherine (who she was named for) and Oliver. Catherine’s nursing home-bound mother’s loss of speech yields to a wordless language more poignant than what she spoke before. As with the snow storm, the physical wreckage does not necessarily lead to emotional ruin. The unexpected connections (between mother and son-in-law, for example, or between a teenage girl and a scary runaway who lives in the attic) are the most exciting kind.

At the end of this novel, many of its threads are not tied up. We do not know how marriages or familial relationships will turn out any more than we did at the beginning. Life’s mysteries, Nelson implies, are supposed to remain nebulous. And the constructions of a narrative (such as a killer expected to kill) do not necessarily mean that answers are given or futures revealed. Only an assured writer of Nelson’s stature can achieve this permeating ambiguity successfully. Instead of conclusions, we have delicate moments of attachment that portend to future feelings of security. And maybe that’s enough. Maybe that is a lot to be grateful for.

Indeed, Bound feels less about permanence or being trapped than it is about restoration. How things are rebuilt after catastrophe strikes. Solidity where before there was vapor. How you shift into the realization of new spaces rather than insisting on what’s come before. A celebration of the protean rather than the mourning of what can’t be brought back.

As Oliver notes, in justifying an affair with a woman twenty years younger than his third wife:

How was it that anybody could be satisfied with only one story? With the surface, and nothing beneath it? With the familiar and repetitive, routine equaling the death of any plausible adventure?

In Bound, it is in the surfacing of these many stories—the news-grabbing and the quotidian, the notable and the everyday, studied and subterranean—that provides the kind of plausible adventures we as readers are lucky enough to find.

Further Links and Resources

at the Nervous Breakdown, where the author recently interviewed herself (2010). Also: Definitely worth reading (if you can track down a print copy) is Andrew Scott’s 2009 interview with Nelson in the Cincinnati Review; he offers an excerpt (on the ways in which novels are “satisfying”) in the Andrew’s Book Club archives.

Antonya Nelson in Berkeley from Al Martinez on Vimeo.