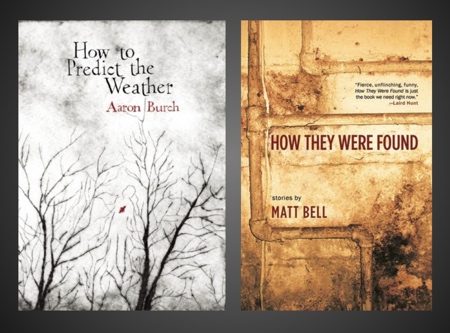

How to Predict the Weather, by Aaron Burch (Keyhole Press, Nov. 2010)

How They Were Found, by Matt Bell (Keyhole Press, Oct. 2010)

The writers of Dzanc Books have received O. Henry and Best American prizes; they have appeared as finalists for ForeWord Magazine’s Book of the Year, the Flannery O’Connor Award, AWP’s Award for the Novel, and numerous other accolades. Since its 2006 founding, Dzanc has staggered the field with fascinating and exploratory writing. Two recent publications from one of Dzanc’s imprints, Keyhole Press – Aaron Burch’s How to Predict the Weather and Matt Bell’s How They Were Found – continue to stretch the imagination, pushing the boundaries of literary fiction.

Composed of brief, independent passages—often single paragraphs—How to Predict the Weather alternates between short narratives and second-person commands. Though distinct, the segments converge on shared themes. Most vignettes feature unnamed couples, into whose lives Burch offers intimate, almost voyeuristic insight. These characters long for freedom and self-expression, desires that might seem trite in lesser hands. Burch enlivens these subjects with images of flight and weather. His figurative language chisels familiar forms into strange new shapes. For example, he defines one couple’s decline through cloud-watching: “The excitement of similar and individual visions in their blotted sky became their special date, their ritual. Then, ritual became routine; routine, a chore. The clouds had the final say.” Characters encounter their limitations through an inability to fly or their subjection to the climate.

Composed of brief, independent passages—often single paragraphs—How to Predict the Weather alternates between short narratives and second-person commands. Though distinct, the segments converge on shared themes. Most vignettes feature unnamed couples, into whose lives Burch offers intimate, almost voyeuristic insight. These characters long for freedom and self-expression, desires that might seem trite in lesser hands. Burch enlivens these subjects with images of flight and weather. His figurative language chisels familiar forms into strange new shapes. For example, he defines one couple’s decline through cloud-watching: “The excitement of similar and individual visions in their blotted sky became their special date, their ritual. Then, ritual became routine; routine, a chore. The clouds had the final say.” Characters encounter their limitations through an inability to fly or their subjection to the climate.

Burch, however, also finds hope in defeat. He commends the value of the journey, despite its unreachable end: “Consider the implications of terminal velocity… Be a bird. Tuck. Point head down, release all thought, enjoy.” He then applies this metaphor to the writer’s task:

Write it down then ball up the piece of paper, push it into your mouth … Take your time, chew slowly, savor … If, when trying to swallow, you cough and have to spit back up some of the dirt, think of the crumbs of the earth as small birds taking flight, transferring from one vessel to the next. Think of it like giving birth to an avian beginning.

Here Burch generates freedom from failure; he sees a new beginning in the coughed up crumbs of the earth—the detritus of written words.

Burch’s stories frequently use physical violence to reflect the intensity of love. His couples devour and cleave one another apart. The book’s opening passage depicts a man folding his lover like a piece of paper, “as many times as he could, counting. He put her in his mouth and swallowed, pushing down his throat with index finger, inviting her to stay forever.” The act of devouring embodies a passion so great, nothing less than complete consumption will satiate it. In a contrasting scene, a man amputates his lover’s hands. “My hands want to make little birds,” she tells him and begs for his help. Together, they saw off her hands to give them flight. With vivid and unsettling imagery, Burch demonstrates the different guises love can take, and the emotional extremes to which it can push us.

A daring work, How to Predict the Weather may frustrate readers searching for a structured plot or named characters. Rather, this collection rewards the open-minded. Burch’s narrative gems—often reminiscent of prose poetry—coalesce into a forceful emotional experience. Ultimately, they present a stunning meditation on love, loss, and the potential of human imagination.

For readers who long for earth, Matt Bell’s How They Were Found offers a compelling alternative. Each of his thirteen stories possesses its own unique and vivid reality. An army platoon struggles to find purpose in a barren, post-apocalyptic landscape; a man preserves a murder victim in a walk-in freezer in his garage; a woman falls for a shrinking homunculus, the essence of her ex-boyfriend. Collectively, Bell’s characters search for meaning and order in these realms of meticulously crafted chaos.

Many of Bell’s tales emerge from the wreckage of failed relationships. In “The Leftover,” the forgotten traits of Allison’s ex-boyfriend manifest in a miniaturized clone, a “smaller version of Jeff, maybe four or five feet tall.” Strange yet familiar, Little Jeff reminds Allison not just of the habits he abandoned for her sake, but of the “qualities that Allison forgot she even missed.” Another story features a heartsore cartographer, who documents his grief with visual landmarks — the language he knows best:

Bell’s prose crescendos with the protagonist’s anguished search, building to a beautiful frenzy:

He annotates until the city appears as a bloated, twisted thing, depicted by a map too full of language and memory to be useful to anyone but himself.

In narratives that feel almost uncomfortably honest, Bell exposes unusual acts of desperation, uncovering raw, new representations of heartache and hunger.

Not only do these stories work cohesively, they appear in a thought-provoking progression. Bell positions “Wolf Parts” and “Mantodea” beside one another, juxtaposing two vastly different portraits of oral consumption. Arguably the book’s darkest work, “Wolf Parts” deconstructs the story of Little Red Riding Hood. The fable’s familiar characters interchange as victim and predator. In one passage, Red takes her grandmother’s place in the bed, and “as soon as the wolf forced himself inside her, she sprung her trap, showing him that she too knew what it meant to consume someone whole.” Bell follows this story with “Mantodea,” which features a man’s insatiable appetite: “I’d once thought I wanted to eat something that could end me, but now I knew I really wanted something else, something approximately the opposite.” “Mantodea” serves as a more realistic foil to the preceding fairy tale, furthering Bell’s conflation of sex, gluttony, and death.

The lonesome souls of How They Were Found also use recorded history as a coping mechanism and a means of preservation. Like the cartographer, the characters of “The Collectors”— a novella—succumb to an urgent need to record. Though the novella appeared in Bell’s 2009 chapbook of the same title, in How They Were Found it engages with the surrounding stories. Based on true events, “The Collectors” details the compulsions of three distinct individuals: the two reclusive Collyer brothers, and the man who discovers their bodies amid their hoarded belongings. This last voice offers a final reflection on history as interpretation:

The lonesome souls of How They Were Found also use recorded history as a coping mechanism and a means of preservation. Like the cartographer, the characters of “The Collectors”— a novella—succumb to an urgent need to record. Though the novella appeared in Bell’s 2009 chapbook of the same title, in How They Were Found it engages with the surrounding stories. Based on true events, “The Collectors” details the compulsions of three distinct individuals: the two reclusive Collyer brothers, and the man who discovers their bodies amid their hoarded belongings. This last voice offers a final reflection on history as interpretation:

To each person, I try to give the thing he has been looking for, to offer him a history of you that will clash with the official version, with the version of the facts already being assembled by the historians and newspapermen. I wanted them to see you as I wanted to see you when I first came to this place, before I started telling your story to my own ends.

This narrator vocalizes the question posed quietly throughout the book: what can one capture with pen and paper, and what escapes documentation?

Bell examines the utility of art even more directly in “An Index of How Our Family was Killed.” The story, more catalogue than narrative, provides an alphabetized account of a family’s unusual deaths, recorded by one of two surviving members. Under “I,” he interrogates the purpose of his documentation:

Index as excavation, as unearthing, as exhumation.

Index as hope, as last chance.

Index, as how to find what you’re looking for.

Index, as method of investigation.

…

Index, as understanding, however incomplete.

Through indexing, the character discovers both the catharsis of writing and the shortcomings of the craft. Bell’s final definition for “index” becomes an apt description for the book itself: “a collection of echoes, each one suggesting a whole only partially sensed.”

With their debut collections, Burch and Bell demonstrate Dzanc’s diversity and its focus on literary fiction that pushes the medium further. Despite dramatically different structures, both books revolve around shared themes. How They Were Found poses a dark counterpoint to Burch’s work. Bell’s more pessimistic lens aligns the act of devouring with emptiness, anger, and lust. The stories conduct a penetrating investigation of human nature, of what happens when you strip individuals down to their barest, most honest selves. Through divergent perspectives, these books investigate the role and responsibilities of literature. No less original or thought-provoking than contemporary fabulist stalwarts like Aimee Bender or Etgar Keret, Burch and Bell expand the scope of experimental writing. They consider new forms of storytelling with books that encourage the reader to think, feel, and engage.

Dzanc and its writers continue to share the spoils of their success, initiating numerous literary programs. Bell edits for The Collagist, Dzanc’s online journal, and Burch founded Hobart, which publishes an online journal, a print journal, and printed minibooks. Dzanc sponsors low-cost, one-on-one workshops for aspiring writers, the proceeds of which go entirely towards charitable efforts. Their Writers in Residence project places established authors in public schools in Michigan and New York. From 2008-2010, Bell taught creative writing at Thurston Elementary School in Ann Arbor.

As small presses struggle beneath economic pressures, Dzanc’s continued success offers hope. It champions invigorating and inventive prose such as that found in How to Predict the Weather and How They Were Found. The press deserves the support of the community it has helped build; fans of explorative, meaningful literature should turn their attention to this innovative young publishing house.

Further Links and Resources

From Aaron Burch:

- “Overcast” in Memorius: 12

- “Drinking in Parking Lots” in Barrelhouse

From Matt Bell:

- “His Last Great Gift” in Conjunctions: 53

- “For You We Are Holding” in Conjunctions: 55