The line between the short short story and the prose poem is a notoriously thin one. I have often taught Robert Hass’s “A Story About the Body” and Carolyn Forche’s “The Colonel,” both originally published in poetry collections, as short short stories, while noting that other selections—pieces by Stuart Dybek or Lydia Davis, for example—would fit just as comfortably on a poetry syllabus. All of the writers listed above deal in narrative, but the narratives that appeal to them when practicing this form are discrete, self-contained. This is the art of the anecdote, observed through the poet’s defamiliarizing eye, and J. Robert Lennon’s Pieces for the Left Hand (Graywolf, 2009) shares with the work of these writers an interest in the precise image and the striking moment of characterization. In the story “Twilight,” the narrator is asked by a group of French tourists for the toilet; believing that they have asked about “twilight,” he directs them to a nearby pier where they will have an excellent view of the sunset. Though the mistake is corrected, he later sees them on the pier and stands “watching them watch until it was dark.”

The line between the short short story and the prose poem is a notoriously thin one. I have often taught Robert Hass’s “A Story About the Body” and Carolyn Forche’s “The Colonel,” both originally published in poetry collections, as short short stories, while noting that other selections—pieces by Stuart Dybek or Lydia Davis, for example—would fit just as comfortably on a poetry syllabus. All of the writers listed above deal in narrative, but the narratives that appeal to them when practicing this form are discrete, self-contained. This is the art of the anecdote, observed through the poet’s defamiliarizing eye, and J. Robert Lennon’s Pieces for the Left Hand (Graywolf, 2009) shares with the work of these writers an interest in the precise image and the striking moment of characterization. In the story “Twilight,” the narrator is asked by a group of French tourists for the toilet; believing that they have asked about “twilight,” he directs them to a nearby pier where they will have an excellent view of the sunset. Though the mistake is corrected, he later sees them on the pier and stands “watching them watch until it was dark.”

Taken individually, Lennon’s stories might appear as excellent, but perhaps not ground-breaking, examples of the form. And yet, when gathered together, these pieces become that most unusual of forms, the collection of linked short short stories—linked by their location, a small upstate New York town that resembles Lennon’s hometown of Ithaca; and by their narrator, described in the introduction as “unemployed, and satisfied to be unemployed.” The narrator’s solitude, which resembles in so many ways a writer’s solitude, allows him to take the long walks and collate the memories that are combined in the collection.

This narrator, thinking aloud, is the most interesting and most problematic element of this project. Lennon uses first person sparingly, and for pages at a time we can forget that these stories are framed by anything other than the most objective intelligence. But when the narrator emerges, talking to a local short-order cook or remembering being lost as a child, we’re led to wonder about the person behind these anecdotes. The slow exposure of his character becomes a sort of narrative striptease, though, in the end, it’s more tease than strip. In a recent interview with Bat Segundo, Lennon states that this narrator’s habit of “archly noticing things” is not quite his way of seeing; however, he also says that about fifty of these one hundred stories come from situations he’s witnessed or anecdotes heard from friends. Are we then to imagine the speaker as J. Robert Lennon, or as a “J. Robert Lennon” akin to Philip Roth’s “Philip Roth”?

This narrator, thinking aloud, is the most interesting and most problematic element of this project. Lennon uses first person sparingly, and for pages at a time we can forget that these stories are framed by anything other than the most objective intelligence. But when the narrator emerges, talking to a local short-order cook or remembering being lost as a child, we’re led to wonder about the person behind these anecdotes. The slow exposure of his character becomes a sort of narrative striptease, though, in the end, it’s more tease than strip. In a recent interview with Bat Segundo, Lennon states that this narrator’s habit of “archly noticing things” is not quite his way of seeing; however, he also says that about fifty of these one hundred stories come from situations he’s witnessed or anecdotes heard from friends. Are we then to imagine the speaker as J. Robert Lennon, or as a “J. Robert Lennon” akin to Philip Roth’s “Philip Roth”?

Given this built-in continuity between narrator and author, the reader will be tempted to put some weight on the gradual revelation of the character who tells these stories, and perhaps the most compelling moments in the collection are those when the first person abandons his observer status and implicates himself in what he sees. This humanizes him, and allows us to get to know and care about him rather than simply do what he does to the tourists on the pier—watch him watching. However, the pieces that include this implicated “I” (I’m tempted to name them stories as opposed to the less personal anecdotes) are far outnumbered by those who begin with “a man” or “a family” in the town itself, in the city, or “in a house on the edge of a forest not far from here.” The abstract folklore-esque quality of these situations is a valid stylistic choice, but limits our degree of investment in the speaker who describes them. I’m certain that if Lennon had chose to frame these stories as third-person, without the conceit of the implied narrator, I as a reader would have had a better idea of how to calculate my own narrative distance. The stories are not seen through the objectivity of third person, nor are they processed through an identifiable point of view—that is, a narrator that the reader has come to know, with necessary human biases and blindnesses. In the end, I’m left wondering how to feel about this faceless speaker, so ubiquitous and yet so much less available to my imagination than the characters he describes.

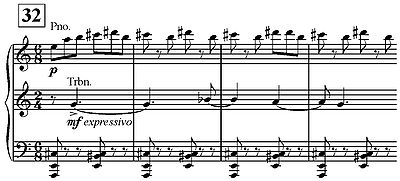

This connection and disconnection between the personal and the impersonal is associated with another dichotomy, between the careful composition that structures and styles these pieces and the casualness invoked by the title. The obvious reference is to the Piano Concerto for the Left Hand that Maurice Ravel wrote for Paul Wittgenstein, commissioned by the pianist after the loss of his right arm in World War I, and in one story, “Lefties,” a professor who has lost his right arm “has learned to play a variety of left-hand pieces on the piano, and is said to be as dexterous with his left hand alone as he once was with both.” These stories, both first and third person, are deeply acquainted with loss and its consequences, and yet the title also suggests a certain casualness, an “offhandness” that is consistent with the conceit of a man processing his own life while walking in the woods. The introduction tells us this about the narrator’s walks:

This connection and disconnection between the personal and the impersonal is associated with another dichotomy, between the careful composition that structures and styles these pieces and the casualness invoked by the title. The obvious reference is to the Piano Concerto for the Left Hand that Maurice Ravel wrote for Paul Wittgenstein, commissioned by the pianist after the loss of his right arm in World War I, and in one story, “Lefties,” a professor who has lost his right arm “has learned to play a variety of left-hand pieces on the piano, and is said to be as dexterous with his left hand alone as he once was with both.” These stories, both first and third person, are deeply acquainted with loss and its consequences, and yet the title also suggests a certain casualness, an “offhandness” that is consistent with the conceit of a man processing his own life while walking in the woods. The introduction tells us this about the narrator’s walks:

[They] began to shake things loose in [his] mind. Dark memories of childhood– his mother’s misery, his father’s death. He began to remember events he had witnessed, stories he had heard, thoughts he had had that he couldn’t let go….Every day, for many months, he sifted through the growing pile of memories, until he began to tell them to himself, as stories. I once knew a man, the stories began.

But the arbitrariness of the memories that give rise to these stories contradict the way in which they circle back on each other, themes of coincidence, misunderstanding and bereavement coming back again and again. Should we read these as random slices of experience, or careful moments interpreted and crafted by an astute observer? Or are they intended to be both at once, as Lennon teaches us a subtle lesson about the way the mind—perhaps particularly the writer’s mind—makes even the worst pain into the stuff of fiction? Perhaps, in the end, this is the real purpose behind the switches between first and third person. Perhaps Lennon is telling us that for the writer, first and third person are really the same—that, as Rimbaud put it, “‘I’ is another.”

It would be possible to read Lennon’s collection and enjoy it, without worrying about any of these things. The voice, acerbic, perceptive, and funny, makes every story enjoyable in its own right. The collection ends a story called “Brevity,” about a novelist who condenses a thousand-page manuscript into a haiku: “Tiny Upstate town/ Undergoes many changes/ Nonetheless endures.” The irony is too apparent to allow us to read this as Lennon’s last word on his own project, and yet in a sense the epigram stands for the collection as a whole—an example of abstraction, condensation and objectivity taken to its most rigorous extreme.

Further Reading

~Visit the author’s website for links to his books, music, and photography. You can also read selections from Lennon’s stories, essays, and other writings here:

~In April of 2009 J. Robert Lennon put together a playlist for Paper Cuts, a book blog on The New York Times online. He writes in the introduction:

I like strange formats and obscure structures. Extremely short stories, poems with absurdly long lines or odd rhymes, conceptual art pieces. I can sometimes be seen stalking around my town carrying a half-frame camera, or in my house noodling on an analog synthesizer the size of a bookcase. I like things that are awkward or don’t quite work. So it’s natural that I would have a penchant for six-minute songs. Unlike jazz or classical music, rock and pop are wedded to a strict format; even the most avant-garde bands usually put out records containing a dozen or so short pieces recognizable as “songs.” In this context, six minutes is just too long. Unless of course it isn’t.

To see Lennon’s ten song picks, visit the Paper Cuts blog.

~You can also listen to J. Robert Lennon discuss his work in a 2009 interview on the Bat Segundo show.

~You can also listen to J. Robert Lennon discuss his work in a 2009 interview on the Bat Segundo show.

~Or check out the podcast interviews that Lennon is conducting with authors visiting Cornell University, where he teaches, for the Writers at Cornell series. His most recent conversation is with poet Billy Collins.

-Lennon’s newest novel, Castle, was also published by Graywolf Press in 2009. The book is about a man who discovers an abandoned castle in the middle of the piece of property that he’s just bought in upstate New York. Buy the book here from your local independent bookseller.