As luck would have it, I’d just begun reading Jacob Paul’s debut novel, Sarah/Sara (Ig Publishing, 2010), when, on a routine visit to the Fiction Writers Review blog, I was greeted by Celeste Ng’s post on “This Book Made Me Want to Die,” an essay by author Aryn Kyle on certain readers’ expressed preferences for “happier” literary fare than what Kyle’s fiction offered them. If happiness is what those readers want, I thought as I returned to Sarah/Sara, they should keep their distance from this novel.

As luck would have it, I’d just begun reading Jacob Paul’s debut novel, Sarah/Sara (Ig Publishing, 2010), when, on a routine visit to the Fiction Writers Review blog, I was greeted by Celeste Ng’s post on “This Book Made Me Want to Die,” an essay by author Aryn Kyle on certain readers’ expressed preferences for “happier” literary fare than what Kyle’s fiction offered them. If happiness is what those readers want, I thought as I returned to Sarah/Sara, they should keep their distance from this novel.

But they’d be missing out on something very special.

Sarah/Sara unfolds as the journal of Sarah Frankel, an American-born Jew who, shortly after finishing her undergraduate studies at Columbia, moved to Israel (in proper parlance, this is called “making aliyah”). There, where she took the Hebrew version of her name (“Sara,” pronounced Sah-rah), she continued to become far more ritually observant and schooled in Jewish texts than she was raised to be.

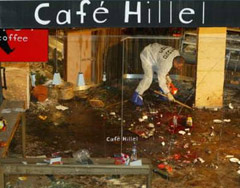

Cafe Hillel in Jerusalem after suicide bombing (9/9/2003)

When her visiting parents were killed in a suicide bombing in the café below her Jerusalem apartment, she became a twenty-three-year-old, sibling-less orphan. The explosion also left Sarah disfigured, although it’s not until more than halfway through the book that we learn some details: “Scars cover most of my face. I don’t have eyebrows. I’m missing half of an ear.” This tragedy was far from the first Frankel family trauma: Sarah’s father, an investment banker who was on the twenty-ninth floor of Tower One on September 11, 2001, survived that day physically, but remained haunted by his experience. The suicide bombing in Israel and the 9/11 attacks are relentless touchstones in this book. The reader can escape their impact no more easily than the characters can. (Oh, and did I mention that Sarah’s mother was the daughter of a Holocaust survivor/orphan?)

As if all of that background weren’t bleak enough, Sarah writes her journal entries throughout what some might consider at best a desolate journey: a six-week, solo kayaking trip through the Arctic. This was the retirement trip her father was planning before he was killed. There’s no denying the scenic beauty (“The tundra amazes me,” Sarah writes in one early entry. “It’s a forest, willow and pine.”).

photo credit: Free Wine

But there’s also no question that this is a dangerous adventure, with everything from polar bears to freezing temperatures threatening Sarah’s survival. These perils are no mere theoretical dangers; they are very real hazards. Further, the trip is shadowed by Sarah’s post-traumatic stress, grief, and guilt. Near the book’s end, when Sarah seems close to succumbing to almost certain death, she is prone to streams of thoughts like this set of “if only”s:

If I’d never become orthodox and moved to Jerusalem, if terrorists had never flown planes into my father’s office building, if my parents had never come to visit me, if that young woman hadn’t decided to kill herself by exploding in the middle of a crowded café, if I hadn’t survived the attack, if I hadn’t decided to finish my father’s boat and complete his retirement dream, if I’d found a more knowledgeable outfitter, if I’d started two weeks earlier or packed an emergency transponder, if I stopped whining so much and instead began searching for that stream. If I didn’t keep worrying that like Job, I was being punished rather than tested.

Jacob Paul

Throughout the trek, Sarah’s thoughts turn not only to her past—memories—but also to an imagined future. Grimness appears even in these fantasies of her post-kayak trip life back in Jerusalem. For instance, she imagines that she will meet a man, Udi, himself grieving a terrible loss (the death of his son), and that the couple will frequent a particular café:

They won’t discuss it, but part of Yechil’s Café’s appeal is the outdoor seating. In a large open area, they will have a much better chance of seeing a bomber before he detonates. Walls amplify blasts, echoing shockwaves with devastating effect. Yechil’s will be a kind of transitory therapy for Sara, a halfway house on the road to full café-recovery. Even the closest bus stop is on the other side of Rechov Ben Gurion and a full half block away. And their meetings will give Udi some structure, a sense of routine, a mandatory, daily perch which will be so important while he wanders Jerusalem’s streets, waiting for the expiration of his mourner’s leave from the army.

As a fiction writer—and as one who has spent considerable time and ink on Jewish characters and families—I was particularly drawn to multiple aspects of this novel. First, there’s the issue of language. The author does a good job explaining most of the less-familiar phrases (one example: “And I’m shomrei n’giah, which means I have no physical contact with men I’m not immediately related to if I can at all help it….”), and I suspect that words such as “Hashem” would be easy enough to comprehend from the context even if one didn’t already know that it serves as a referent for “God.” But at times, I struggled to make sense of sentences such as “Hashem made the yetzer harah to inflict us with taivah.” A prayer called Shemonah Esrai similarly sent me directly to that glossary we know as Google.

Incorporating what an MFA instructor once memorably derided in workshop as “foreign words” in one’s fiction is, I’ve realized, something that some of us simply can’t avoid. It’s something that makes perfect sense in this novel, where the very title suggests the inherent tensions between the protagonist’s secular Jewish-American and orthodox Jewish-Israeli selves. It indicates on small but identifiable levels—such as the Frankels’ expressed discomfort with being called “Eema” and “Abba” instead of “Mom” and “Dad”—a much greater conflict between Sarah and her parents, what Sarah calls “our ideological split.”

at the Western Wall / photo credit: Ram Viswanathan

Here, I move into delicate territory. For the divisions that can arise within what might be called “the Jewish community” or even within individual Jewish families over religious observances and Israel are not easy to talk about. But talk about them (in her journal, at least) Sarah does. She describes herself as having been born into a comfortable Diaspora Jewish identity. Her parents—her mother, especially—do not approve of her embrace of Orthodox Judaism and her move to Israel. It’s not just rituals and language they have difficulty accepting. In one post-9/11 telephone conversation, Sarah listens as her mother rails:

‘That’s why your Sharon’s policies in the occupied territories will never stop terrorism. The more fear he creates; the more fear will seek outlet. People who do not fear, who are not oppressed, hunted, haunted by occupiers, they strive to avoid a situation of fear, strive to preserve a status-quo; those kind of people would never blow up buses or fly planes into buildings.’ I asked her if she wanted me to start with her insistence on calling the land Hashem promised us in the Torah occupied, or would she rather I addressed the massive success of Jewish passivity during the Shoah, or would she simply rather I dropped the subject?

Sarah’s father’s feelings in this respect are somewhat milder. As Sarah recalls, “his primary complaints were that I lived too far away and that I fought with my mother, not that I’d adopted the faith of my forefathers.” Still, even within this small family of three, one manages to obtain a glimpse into some of the varieties of Jewish experience and attitudes. This alone is a significant accomplishment.

Then, since we often find much made of women authors who attempt to write in the first-person point-of-view of male characters, it seems appropriate to address Paul’s work as a male author writing in the voice of a female protagonist. Two observations seem worth making here. First, Paul consistently takes into account the prescribed gender roles of traditional Orthodox Judaism. (He also takes on some of the stereotypes, as when Sarah recalls that her longtime—and non-Jewish—best friend, Marie, had tried to dissuade her “‘from having a shitty life living with some stuck-up pretentious Jew who kept you cloaked like a sheik’s wife.'”) And then, Sarah’s awareness of her body while she is on the kayaking trip is not limited to muscle strength or soreness. Her menstrual cycle receives attention, too. I’m not sure I’ve seen many male authors tackle lines like this:

photo credit: Nick Russill

My trainer suggested going on the pill to suppress everything altogether. She said it would be more convenient…I wish I had gone on the pill; I don’t want this here, now. Even if I wasn’t susceptible to the fearful suggestion that my body has secretly sought to contact predatory bears, I would not want to deal with double-bagged used pads, cleanup, hygiene.

Finally, I return to the book’s darker qualities. It’s not altogether inconceivable that after reading Sarah/Sara, someone might be inspired to follow the example of Aryn Kyle’s readers and claim that “this book made me want to die.” But for the more discerning reader, one who identifies with and marvels over what Laura van den Berg has lauded as “stories that make my heart hurt,” Sarah/Sara will be an important—and impressive—read.

Further Resources

– Excerpts from Sarah/Sara are available on Numéro Cinq, author and professor Douglas Glover’s site for his students in the Vermont College of Fine Arts MFA in writing program (of which Jacob Paul is a graduate; he also holds a PhD in Literature and Creative Writing from the University of Utah), and on Paul’s own website.

– While touring for Sarah/Sara (on bicycle), Jacob Paul wrote a series of blog posts for Mountain Gazette. You’ll find them, in chronological order, here, here, here, here, and here.

– Although not available online, the July/August 2010 “First Fiction” feature in Poets & Writers spotlights Jacob Paul and Sarah/Sara.

– KRCL (Salt Lake City) conducted this interview with Jacob Paul in May 2010 (complete with complementary playlist).

– At Write the Book, listen to a podcast interview with the author (July 2010) and find a writing prompt inspired by Paul’s work.

– Laura Ellen Scott has reviewed Sarah/Sara for Prick of the Spindle.

– Watch and listen to Jacob Paul introduce the novel in this video: