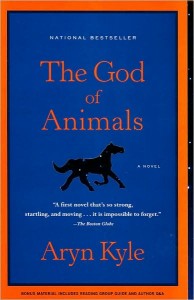

In her debut novel, The God of Animals, Aryn Kyle illuminates how uncomfortable—physically and emotionally—it is to grow up, especially when you’re forced to do so before you’re ready. Even though Alice Winston is a sixth grader with the responsibilities of an adult (helping her father, Jody, manage their stable; completing countless chores; looking in on her shut-in mother; worrying after her runaway sister, Nona) she never comes off as a clichéd wise child, someone whose innocence allows her clear, preternatural vision into the flawed motives of the foolish adults under whose care she’s expected to learn how to live.

In her debut novel, The God of Animals, Aryn Kyle illuminates how uncomfortable—physically and emotionally—it is to grow up, especially when you’re forced to do so before you’re ready. Even though Alice Winston is a sixth grader with the responsibilities of an adult (helping her father, Jody, manage their stable; completing countless chores; looking in on her shut-in mother; worrying after her runaway sister, Nona) she never comes off as a clichéd wise child, someone whose innocence allows her clear, preternatural vision into the flawed motives of the foolish adults under whose care she’s expected to learn how to live.

Kyle avoids these child-narrator pitfalls by making Alice’s coming of age physical—tangibly painful. Narration like, “I felt myself having a growth spurt,” can’t come off as wooden because Alice says this while squeezing into too-tight jeans during a record-hot summer in the desert; she’s “will[ing] herself shorter” so that her swimsuit won’t dig welts into her shoulders. Even as Alice wishes for clothes that fit, she recognizes that any income from her father’s sole riding student, Sheila Altman, should go towards paying bills and fixing the broken air conditioner. When she watches as her father instead splurges on embellishments (fresh paint, fancy saddles, an all-but-untrainable trophy of a horse) fit for a fantasy stable, not the ramshackle operation he’s running. Alice learns that the difference between her and the adults in her life is that they have the money, so they get to make the decisions.

Alice is not so much becoming an adult as she is being forced to act like a one because the grown-ups around her are so childlike. She reacts to her father’s whims and her mother’s total absence the way a long-suffering spouse might; she fumes and mourns in silence.

She also lies. Alice lies to herself and to others—mostly about herself to others. She lies for the same reasons we all (fiction writers and readers alike) do, to protect ourselves and others from the pain of the truth. Alice’s lies, like fiction writers’, come from a combination of observation and imagination.

Many of these lies emerge from the relationship she has with her father’s student, Sheila. Alice is dismissive and envious of Sheila, who is essentially the only young person in Alice’s life. The other is the ghost of Polly Cain, a former classmate whose death by drowning opens the book’s stunningly rich (especially setting-wise) first chapter, which originally appeared as the short story, “Foaling Season,” in the Atlantic Monthly. Alice lies to Sheila and her mother, Mrs. Altman, with regularity, at first mostly to keep Sheila as a student and protect her father’s business (and her own livelihood). She tells Mrs. Altman that she witnessed a competing trainer abuse a horse, and she repeatedly inflates her assessment of Sheila’s riding talent and potential (as does Jody).

Later, a romanticized version of Sheila’s life provides Alice with source material for an alternate version of her own, created especially for Mr. Delmar, the English teacher who becomes her first real crush, in part because he is such an important audience for her lies.

Alice’s lies are the one place in her life where she can exhibit control and, more importantly, where she can have the sort of rich fantasy life so often associated with childhood. In the lies she tells Mr. Delmar, she can co-opt all the shimmer of Sheila’s life (the educated astronomer father; the plush, perfect-for-sleepovers-bedroom) without any of the ugliness she’s actually witnessed there (the philandering husband, the offhand cruelty of sleepover guests).

In her relationship with Mr. Delmar, Alice exploits another of dishonesty’s functions: to connect. Fascinated by a classmate’s description of Mr. Delmar weeping in his car at the news of Polly’s death, Alice goes to see him after school under the pretense of getting a head start on next year’s reading list. She compounds her lie when he asks whether she and Polly were friends. She reasons, “Each of us had suffered over her—this was the real truth. Nothing else mattered,” before telling him that Polly had been her best friend. For a moment, she’s guilty, “dizzy under the weight of what couldn’t be taken back.” But the power in the lie—the conversation it starts and connection it affords with Mr. Delmar—quickly surpasses any shame. When Mr. Delmar observes that Alice looks like Polly, Alice speaks another small lie and feels “the world around [her] melting away until there was no history, no future, no truth.”

In her late-night conversations with Mr. Delmar (on stolen time when each parent believes she’s with the other) Alice creates the sort of life she might have had some chance at actually living, if she weren’t so busy growing up too quickly. With these scenes, Kyle smartly reminds us that Alice is, despite her skill in deceit, still an adolescent; she describes the pink phone the girl clutches, its chord stretched into the closet where Alice can conduct her storytelling privately. Even at the end of their relationship, with Mr. Delmar leaving town, and the flimsiness of the love Alice thought she felt for him exposed, the truth still proves to burdensome to share. In their final interaction, which takes place in person rather than over the phone, Alice admits to Mr. Delmar that her father is a bus driver (a second job taken to supplement the failing ranch), and not the jetsetting professor of Astronomy she’d described. But she can’t bear to strip away any more falsehoods,”…there was too much truth already, spinning around me, swelling through my mind. Any more, and I would have drowned in it.”

While Alice’s lies may serve in large part to protect herself from what’s painful, they also function as an act of great empathy: her lies protect her loved ones’ fragile hopes.

Kyle complicates the notion of coming of age; Alice is “a little liar,” but it’s the adults who are playing make-believe. Alice recognizes that growing up means accepting there’s no glamorous way to explain away her mother’s consuming depression, her father’s failed dreams for the ranch, her sister’s broken marriage. Her English teacher is not a worldly, dreamy poet, but a sad drunk. Polly Cain is not a wise ghost to be summoned with a séance, but a dead girl who’s not coming back with the answers Alice craves.

Shaping her lies, Alice is not so much preserving her idealized versions of these characters as she is protecting their own hopes—the chance, however slim, that they may become the things they say they to want to be—that they may actually live the stories they tell about themselves.

*

In that perfect first chapter, Sheila begs her mother to allow her to spend the night in the horse barn, hoping to watch a broodmare give birth. Sheila’s mother concedes: “Tomorrow is a school day, but for something like this—this is a life lesson, and I think that’s more important. You’ll get to see the miracle of birth. It’s the most beautiful thing in the world, isn’t it, Alice?”

Alice desperately wanted to attend Polly Cain’s funeral that day, and the birth of the season’s first foal has derailed her plan. She thinks:

“I wanted to tell [Mrs. Altman] about the blood and the smell and the sound a mare made when her flesh began to rip around the opening for the foal. I wanted to tell her about our bay mare a few years back, whose uterus had come out when she birthed and hung behind her like a sack of jelly. I wanted to tell her that the bay had screamed a human scream but stood, trembling, to let the foal nurse. I wanted her to know that when the vet had come to put the mare down, Nona covered my eyes, but I could hear the bones crack when she hit the ground, the foal had cried out in its watery whinny for three whole days afterward, but I smiled and said, ‘Yes. Beautiful.’”

An all-purpose lie, this one. Good manners, good business sense, good girl. A lie to protect, certainly. But it’s also possible that, with this lie, Alice hopes that through Sheila, she’ll get to see that in all that blood and pain she’s grown so inured to, there may actually be—if not a miracle—at least some rough beauty.

And here, another reason fiction matters: sometimes we get to see that beauty, too.