“Prolix! Prolix! There’s nothing a pair of scissors can’t fix.”

— Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds (“We Call Upon the Author to Explain”)

I thought about using a more purely literary quote for this essay—Elmore Leonard’s’s “Skip the boring parts”—but that’s an oversimplification, and I want to speak against oversimplification. (Besides, Nick Cave is a terrific writer with two novels under his belt, and his album notes look and read like chapbooks; he deserves to be quoted by writerly types more often.) Fiction writers are admonished to cut, cut, cut at least as many times as we are urged to write every day. And while it is generally sound advice, it is also terribly easy to misapply.

Thousands of pieces of fiction annually grow stronger by cutting, but those aren’t the ones I worry about. I’m concerned for those that have the life and soul torn out of them because the scissors of concision are wielded with no apparent purpose other than cutting for its own sake. A lot of this kind of cutting happens in response to critique from workshop leaders or peers who have seen other pieces improve through cutting, and who pass on the well-intentioned dictum without thinking, as if it applies to all pieces at all times.

Which is, of course, untrue. Six-line prose poems have turned into eight-page short stories. Novellas have bloomed into trilogies. Novels have gone from 280 pages to 320 pages and gotten better, not worse. Sometimes pieces get bigger not because they become bloated with needless words, but because they tell more story, and sometimes more is exactly what a work needs. In the interest of making a work “tighter” we often reach for the scissors because we’ve been instructed to cut, cut, cut. Telling more story in the same number of pages can also achieve the tightness we desire, perhaps to better effect. We tend to confuse brevity with tautness, though plenty of work—especially today, with the ubiquity of abstract, absurdist flash fiction—is guilty of having so little story that it can’t become taut no matter how stripped down it is.

In the worst-case scenario, premature cutting for its own sake doesn’t serve the tale, and it can even cause a tale to die before it has a chance to blossom. I don’t know how many works of fiction die annually from such premature cutting, but I do know that writers who teach or critique their fellow writers need to encourage the responsible use of scissors for a specific purpose. Scissors need to serve a controlling idea, and if that controlling idea is absent, then tightness is merely an attempt to write like somebody else (frequently Raymond Carver or, in the case of abstract, absurdist flash fiction, Donald Barthelme).

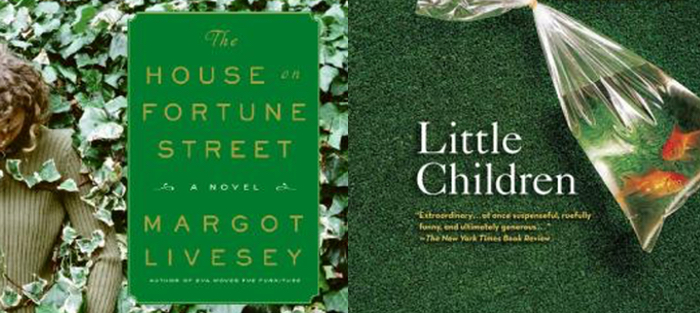

One way to look at the scissors question is through the figure of the narrator, which we can talk about regardless of whether a work is in first, second, or third person. I know that I’m in the minority in speaking of narrators when discussing third-person point of view, since some writers only acknowledge its existence in first person. But all tales have tellers, and these tellers vary from story to story and book to book; if they didn’t, all work by a particular writer would sound the same across the board, or be determined by the vagaries of mood and circumstance. If narrators don’t exist in third person POV, then how can we accommodate books that follow multiple characters in close third person, such as Tom Perrotta’s Little Children, or blend close third person with first person, such as Margot Livesey’s The House on Fortune Street?

Narrators exist across the spectrum of fiction, and plenty of people use more than one narrator in a single work. These multiple narrative personae notice different things, and they represent the psyches of the characters they follow in different ways. They serve as periscopes looking into the author’s fictive world, and as the interface between the author and the reader. Narrators guide our attention, and they can change considerably as authors move from draft to draft. They are what changes first—a small loosening of diction, a hint of more or less desperation, an increased willingness to let characters suffer for their wrongs—when authors want to chart new pathways through their fictive worlds that are more elucidating, more suspenseful, more concrete than those in previous drafts.

Narrators, over time, tend to speak their truths more bravely and bring us more directly to the heart of things. As we work through the drafting process, changing lines here and there—and yes, skipping the boring parts—we’re actually arriving at more precise narrative personae that allow us to work with more confidence and render our characters more decisively. How often have you heard a fellow writer say, “I just found a new voice for this draft, and I love how vague and imprecise it is!”? The great joy of working through drafts in fiction is to see sharp focus emerge from blurriness, to hear innuendo-filled dialogue turn into direct personal challenge, to feel murmurs of understanding and desire become actions in the flesh.

This, not concision for its own sake, is what we should aspire to when we take out the scissors and cut our fiction. If we tweak our work only to make it appear more taut—though it never contains more story, and though its truths are never spoken more sharply—then we embrace concision as a mere stylistic ornament. Ultimately I agree with Nick Cave: there’s nothing a pair of scissors can’t fix, as long as we’re wise about how we use them—to serve the work, not some knee-jerk reaction to cut, cut, cut.

Maybe that project on your desk or bookshelf doesn’t need cutting after all. Maybe it needs more of a story to tell, or a bolder narrator to tell it.