“The point about working is not to produce great stuff all the time, but to remain ready for when you can.”

—British musician and artist Brian Eno

Now that National Novel Writing Month is over you have two choices, depending on which path you chose at the start of November. You can either (a) groan in exhaustion after all your hard work, or (b) sigh in relief that you didn’t start a novel, and banish the lingering fear that you should have done it just to prove to yourself that you’re serious.

Okay. Maybe more than two choices… This year, as in past years, wonderful projects got begun in November and will live to be rewritten assiduously until they sing, while others—perhaps no less wonderful—fell to the earth stillborn and will never leave the box where they got buried. In the aftermath of NaNoWriMo, I propose another month-long project: NaDoWriYoNoMo (National Don’t Write Your Novel Month), a chance to give yourself a vacation from novelizing for a while, whether you’ve been pounding away at one or… well, slacking off and avoiding one.

Note that I didn’t say a vacation from creative work, only from novelization. If you’ve just finished a novel draft, you no doubt need a break and something else to think about. If you’ve been avoiding a novel, maybe you need a little structure to your avoidance so that when you’re ready to dig in, you’ll have a fresh, hungry imagination. In either case, here are three things you can do to keep your inner writer attentive and prepared.

Get outside and walk. You’ll get in touch with your body’s rhythms and, by extension, with the rhythms of language. You’ll also notice a lot more about the world when you travel through it by foot, and that can’t help but make you a more observant storyteller. Charles Dickens, the Stephen King of his day, was a prodigious walker. Is there a writer out there who had a more intimate knowledge of his literary territory than Dickens, who knew the streets of London so well because he walked them so often?

Create a new writing metaphor for yourself. We all have our own metaphors for the novel writing process that help us visualize its long, slow churn. Laying down the voices in a symphony. Building a house. Fishing. Painting in oil. Fallow periods are great times to find new metaphors, and that might prove helpful when you get back to you novel. After all, learning how to write it with emotional honesty will be different from learning how to write anything else you’ve ever written. A bowling metaphor? A baking metaphor?

Dabble in a completely new art form to shake up your creative process. Do you like to write fiction, but have never tried poetry? Ever feel tempted to record some first-person monologues on video? Now is a great time to do it. There’s no pressure on you to produce, only the opportunity to play and let your creative sensibilities find a new outlet. It’s a great chance to re-learn the concept of creative freedom, which is absolutely portable from form to form.

Though the idea of NaDoWriYoNoMo is an obvious lark, there’s some serious thinking behind it. The discipline to write daily is great and necessary; but when that discipline turns into a too-rigid structure just for the sake of writing every day (as it can during NaNoWriMo, with its onerous word-counts), it becomes a prison that serves neither your writerly self nor the project you have handcuffed yourself to. Equally great and necessary is the discipline to recognize when you need to take time away from long-term, grind-it-out projects like novels and refresh yourself—not by being creatively inactive, but by taking new kinds of risks.

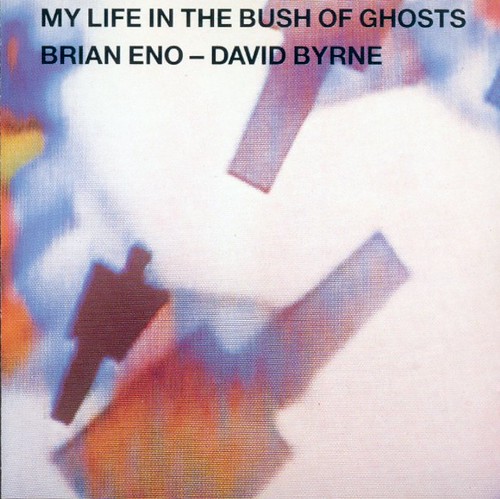

You may remember the above-quoted Brian Eno as a pioneer of ambient music in the 1970s, as U2’s longtime producer, or as David Byrne’s partner on the seminal radio loop album “My Life in a Bush of Ghosts” (its title borrowed from a novel by Nigerian author Amos Tutuola. He’s a man we can certainly say has had not only a creative career, but a creative life. Recently I ran across an article by Scott McDowell called “Developing Your Creative Practice: Tips from Brian Eno” that voiced—in a more articulate way than I can muster—my sense that creative practice is fundamentally the same across the artistic disciplines, and that what’s good for you in painting is good for you on the page.

Frankly, I wish I’d seen this article earlier in my life because I would probably have more fully developed my sense of the synesthesia between creative forms. (My desire for this has never gone away. I have dreams of sculpting in marble and routinely play things on the saxophone that I wish I knew how to transpose into musical notes.) The work of the novelist isn’t fundamentally that much different from the work of the composer or the muralist, which is precisely why our personal metaphors for writing help us to envision what we do. To be an artist in any form is to commit yourself to acts of perception and creativity over which you have limited and uncertain emotional control—and then, by using the craft and aesthetic control that you’ve developed, shape that uncertain spark into a work that can be perceived by others.

This is not the kind of all-over-the-place spaciness that our high school classmates made fun of when they called us “artsy-fartsy.” It’s the opposite: a cultivation of one’s state of receptivity, which functions within us even when we are not working on our “A-list” projects. In pursuit of this synesthesic creativity, Eno is bullish about discipline. “The reason to keep working is almost to build a certain mental tone,” he says, “like people talk about body tone. You should stay alert for the moment when a number of things are just ready to collide with one another,” because when they collide, your best art happens. If you don’t keep things moving, then your chances of a collision fall to zero.

Why shouldn’t the creative chances you take in a less familiar artistic discipline make you more receptive and “toned” overall, so that you’re sharper in the discipline you’ve chosen as your primary one? No reason. They can flow over, and they will if we invite them. So while I don’t—emphatically don’t—advocate the idea of waking up in the morning and saying “I don’t feel like writing today,” I do advocate stepping away from all-consuming fiction projects from time to time and finding new ways to exercise your creativity. So whether you’ve just finished cranking out a novel draft or are still waiting for the motivation to start one, please read McDowell’s article on Eno and gift yourself, as we start NoDoWriYoNoMo, with a few strategies for creative refreshment.

Quotes and Notes is a craft essay series by Steven Wingate. His short story collection Wifeshopping won the 2007 Bakeless Prize in fiction from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and was published by Houghton Mifflin in 2008. He is an Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at South Dakota State University.

Quotes and Notes is a craft essay series by Steven Wingate. His short story collection Wifeshopping won the 2007 Bakeless Prize in fiction from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and was published by Houghton Mifflin in 2008. He is an Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at South Dakota State University.