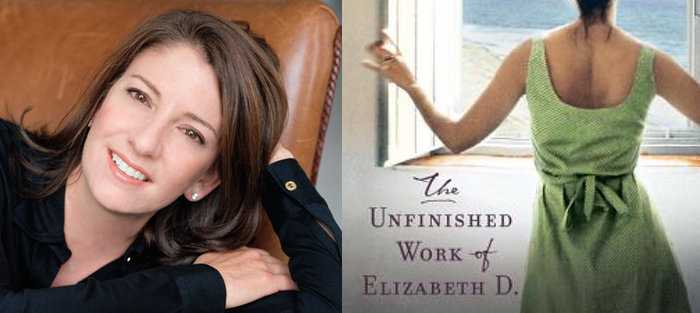

My first contact with Nichole Bernier, apart from the general hubbub of Twitter, came when she reached out to me to ask if I’d like her blog to mention my recently published story collection on a feature they had about books that had just come out. It was my first book, and I remember being stunned that anyone outside my family, agent, or publisher would think of helping me this way. It seemed like an extraordinarily gracious thing to do. That was more than three years ago, and in that time I’ve learned a couple of things about Nichole Bernier. One is that she is indeed extraordinarily gracious, the sort of colleague who makes you wonder where all the famous competitive literary snarkiness has gone. Another is that she’s a hell of a writer, too.

I read Nichole’s debut novel, The Unfinished Work of Elizabeth D., in manuscript form while on vacation with my husband in Provincetown. I’m not one of those people who remembers exactly where she was when she first read every book she’s ever read—in part because I don’t usually read books in just one place. A few pages at home, a few pages at a coffee shop, and so on. But I remember reading Nichole’s novel while sitting in one chair, the door to a small balcony open, the bay just across the street. I didn’t move from the spot. It was a reading I’d been nervous about, because by then I’d known Nichole for well over a year and I liked her enormously, so, as with every friend’s work, I was terrified that I wouldn’t like it. But, as I said at the time, Nichole writes like she was born knowing how.

There’s a kind of crystal clear quality to her prose that I have gone back to study and tried to emulate more than once. And while on the surface hers is a book about women who became friends while raising their kids, it is more accurately about a subject dear to my heart: the secret lives that we all lead and the limits of our capacity to know one another as well as we might wish. I believe that we are always up against those limitations to intimacy and that the way we navigate those limitations define our human qualities. The Unfinished Work of Elizabeth D. gave me a chance to ponder those ideas once again—and no choice but to stay in that chair by that lovely view for a full day because I truly couldn’t put the book down.

Since reading her first novel, I’ve come to know Nichole better still. But I used this interview as a chance to learn a little more about the many secret selves that dwell within my dear friend.

Nichole Bernier is the author of The Unfinished Work of Elizabeth D., which was a finalist for the New England Booksellers fiction award and a Target Emerging Author selection. She served as a Contributing Editor for Conde Nast Traveler for fourteen years, and was previously on staff as an editor, columnist, and television spokesperson. She received her master’s degree from the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, where she received the school’s award for literary journalism, and has written for publications including Psychology Today, Elle, Self, Health, Men’s Journal, Salon, The Millions, and Post Road Literary Magazine.

After she married and moved to Boston, she joined Boston Magazine as a senior editor. She is one of the founders of the literary blog Beyond the Margins, which features daily essays on the craft and business of publishing.

Interview:

Robin Black: I thought I’d start with something a little out of left field. Recently, now that I’m more than a decade into being a full-time fiction writer, I have become obsessed with how strange it is that I—and other fiction writers—spend so much time every day with people who don’t actually exist. It’s such a weird occupation, I think. And I’m especially puzzled in my own case because I think of myself as a very reality-based human being. So in thinking about what conversation I’d like to have with you, I realized that I’m curious: What it’s been like for you spending so much time in your own imagination, creating alternate realities, especially since you started in journalism? Was there any resistance in you as you went from the journalist’s version of sticking to the facts to the very different ways in which fiction writers may feel bound to some kind of truth? Does it ever just surprise you how much time you spend making stuff up? Because I’ll admit, I do find that odd sometimes.

Nichole Bernier: It was very strange initially to give myself that kind of license. But everything about beginning to write fiction was strange—creating imaginary people and worlds, taking so much time away from my family to write and endlessly revise something no one had assigned.

Nichole Bernier: It was very strange initially to give myself that kind of license. But everything about beginning to write fiction was strange—creating imaginary people and worlds, taking so much time away from my family to write and endlessly revise something no one had assigned.

But the biggest oddity for me of going from fact-based reporting (or even narrative nonfiction) to writing a novel was the freedom to pluck from thin air whatever you needed to flesh out your story. What cheating! In my magazine articles, if I needed a quote from someone who, say, was experiencing financial loss because of the state of the real estate market, I’d have to go out and find them, and hope they’d say something that supported my research. In fiction, if you need supporting detail to justify a character’s behavior, you invent the backstory that makes the character’s evolution and subsequent actions feel authentic.

But I do have an odd rigidity about facts and truth. If in my novel I referenced an event that bore resemblance to something that has actually occurred (a plane crash in Queens, a bombing in Bali), I was dogged about the true date of that event, or citing the departure from it in the acknowledgements. A real thing is a real thing. Along these lines, I named my book’s island something other than Martha’s Vineyard because I didn’t want to misrepresent the geography, or be restricted by each mile marker and shrub. I used to work at a travel magazine. I know the importance of locational accuracy. AND the way readers call you on it when you slip up.

However, the one thing that was not strange was giving value to the act of fictionalizing, which I think is hard for journalists. I didn’t feel it was any less worthy to spend my time on people and situations who didn’t exist, because I’ve always been an avid reader of fiction, and find tremendous emotional truths there. At times I’ll read items in the news and think, I’d like to hear the story behind that story. Not just the what, but the how and why.

I totally understand what you’re saying about Martha’s Vineyard and being responsible for getting each signpost right. When I started writing I never used actual places, maybe in part because of exactly that fear. This most recent book, though, takes place in and around Philadelphia where I’ve lived for twenty-five years now, and I still have a feeling someone’s going to lecture me about why it’s impossible for my narrator to have made a left-hand turn onto South Street.

But onto larger issues…I have long believed that the basic question of why people do what they do is at the center of all good fiction, and that one of the justifications for fiction, beyond pure entertainment, is that by placing that question so centrally, it encourages people, readers, to ask that question in “real life” more actively. That’s really what empathy is, I think, and that’s the basis for compassion, being curious about what’s motivating other people—even when at times their behavior is inexplicable.

All of which makes me think of your novel, The Unfinished Work of Elizabeth D., because in a sense what happens in the book—a central character learning about a deceased friend through reading her diaries—mirrors the reader’s experience. I was wondering if you thought about that at all at any point, or if now you have any thoughts about the echoing that has to happen on some level with a novel that is itself about reading?

A novel about a main character reading someone else’s journals is a bit of a funhouse mirror—reading about someone reading about someone—and more of a challenge than I realized it would be. Reading is by nature a static activity, which means an author has to create dynamism in other ways. There would be a certain amount of shock/poignancy in surprises revealed in the journals, but the depth and gratification would come from the dawning awareness of why the journaler made the choices she did, and the juxtaposition of what’s going on in the surviving friend’s own life as she reads. Which is true of all of us as readers of novels, isn’t it? We come to a book from wherever we are, with whatever baggage we’ve acquired.

I didn’t like dwelling on the craft conundrum of reading-a-novel-within-a-novel too much, at least when I began writing. It felt like focusing on Oz behind the curtain rather than letting myself fall into the world of the story. On some level this might be why I went at the writing process by writing the entire life of Elizabeth in her journals first, really sat in her chair, before I wove an external plot around them. I thought it was a very backward thing to do, and that I was somehow missing the “right way” to write, chronologically.

I’m not sure I knew that about your process. It makes a lot of sense to me—though what I find most striking is how we’re all haunted by this idea that there’s a right way to write a novel, when it’s so obvious, intellectually anyway, that there isn’t. First of all, they’re all different. I love the idea—expressed by more than one person—that you never can learn how to write novels, only the one you’re writing at the time. The next will be a whole new learning experience. But maybe more importantly, there just can’t be a right way to make art—because there can’t be a wrong way.

I’m not sure I knew that about your process. It makes a lot of sense to me—though what I find most striking is how we’re all haunted by this idea that there’s a right way to write a novel, when it’s so obvious, intellectually anyway, that there isn’t. First of all, they’re all different. I love the idea—expressed by more than one person—that you never can learn how to write novels, only the one you’re writing at the time. The next will be a whole new learning experience. But maybe more importantly, there just can’t be a right way to make art—because there can’t be a wrong way.

Which makes me wonder about the whole MFA / No MFA question. You do have an advanced degree in Journalism, but not the MFA experience—for better and worse. Do you feel like that’s had an impact on your views of yourself as a writer, or on how others receive you?

I have a lot of thoughts on this, from the MFA side of things, and know why it was a good move for me, but I’m always curious about how successful authors—artistically and in terms of being published—who didn’t get that particular kind of experience feel about the whole thing. (I also sometimes wonder how Jane Austen, George Eliot, William Shakespeare, Henry James, and so on would have felt about MFA’s…I’m guessing they’d be unimpressed. )

I’d love to hear more about your MFA experience. Part of me really wishes I could sink into an intense period of studying writing that way. Getting an MS in journalism was so professionally and creatively satisfying for me, though like the MFA it was hardly a requirement for the field. In fact, I learned after graduation that many editors have mixed feelings about j-school applicants, believing green reporters gain the most valuable learning on the street.

They’re right in a way. And yet I received more critical feedback and development there than in any job I’ve held before or since. The classes and workshops helped shaped my reporting work ethic, as well as my sense of structure and style (my “major” was long-form literary journalism), and I formed some wonderful relationships there. My classmates have moved on to such interesting places.

I’m sure the same would be true of an MFA. I would love to pursue it. But with five kids, and the pace of our life, it’s not in the cards. I’ve had my turn at schooling, and fiction for me is going to be a learning-on-the-street thing. And when it comes to fiction, the street is not a bad place to be. I learn so much from reading authors I admire, talking craft with folks at conferences and on our writing blog Beyond The Margins, and working with my amazing writing group. Every time I read a friend’s manuscript it’s a learning experience in a way: observing why they made this choice and that one, discussing whether it would be better taken from a closer or more distant point of view. Reading your gorgeous upcoming novel Life Drawing (Random House, 2014), was exciting for me, the honest, eloquent, and dark insights into mid-life marriage. I knew that after a few other starts at novels this one simply spilled out of you, and I could see why and how. That’s my brand of learning these days.

Thanks so much for that! I very much appreciate it. And what is your process in terms of sharing work, getting critiques? There’s such a range of how authors feel, some seeming to run every few pages by a reader and others who wait and wait until they feel it’s finished. I find that with different projects, I have different approaches. Do you have a routine? Do you think it will be the same for book two as for book one? How do you sort through the helpful responses form the less helpful ones? I think that’s a skill with which many beginning writers struggle. Maybe some of us not so beginning ones too, depending on the day.

Funny you’d ask. Today I just hit “send” to share the first half of my next novel with my writing group, and I’m jumpy as a cat, giddy as Christmas.

I’m more of a wait-to-show writer, or at least wait-until-there’s-something-significant-to-show writer. And this manuscript is finally far enough along to benefit from comments on structure and character development.

For my first novel, I came up with a weirdly mathematical approach for synthesizing critiques. I made a chart of the suggestions from beta readers (which, for better or for worse, included detailed passes from a few literary agents I’d queried too early). The chart illustrated which points overlapped and from whom, so I could size it up at a glance and get an overall gut check on what rang true. I have no idea if I’ll do it that methodically this next time. Something tells me the process will be more intuitive, less regimented. The first book was a learning process in every way.

I came up in the tradition of workshopping everything—and it took me a while to realize how very bad I was at synthesizing or gleaning (or whatever the correct verb is) the information coming at me. I do much better now writing something all the way to its end and then sharing it with very, very few people. I mean, I’m hoping the result of that process is better; I know the mental health part is better for me.

And speaking of mental health, maybe it’s time for a topic that I know drives both of us crazy, but that is also, these days, the elephant in the room when two middle-aged women writers who happen to be mothers talk about the profession. Gender. Gender and age. Gender, age, motherhood. Gender, age, motherhood, and…genre? It’s hard even to know how to put it because so many of these things seem to weave together. You and I have both published first books that highlight the domestic sphere, and lean heavily toward the topic of families, yet I know, in my case, I resist the pull toward discussions about motherhood and writing. At some point, I became pretty militant about wanting to be seen in professional circles as a writer who happens to have children rather than a mom who writes. The last time I was asked to be on a panel about being a parent who writes, I refused, not because I think it’s unimportant, but because I think it’s so, so easy to let that one aspect of one’s life—mothering; not so much fathering—be a disproportionate professional identity.

But in your case there’s no getting around the fact that it’s just amazing that you have accomplished all you have with five young children. So how do you handle both acknowledging that and not allowing it to be the first thing people think of, when they should be marveling over your work? (With apologies for calling you middle-aged.)

Oh, man, where to begin. Do I mind when this comes up? It depends on the context.

There are certain facts. I have five kids, which is unusual to many people, and my youngest is still in preschool. While I’ve been writing for as long as I can remember, I’ve never written fiction except as a mother, and it’s tempting for people to invoke the whole minivan-scribbler thing. It’s an easy cartoon to reach for. But it really undercuts the seriousness and difficulty and aloneness of the writing process.

Parenthood is a big part of who I am, and what I am and am not able to do, and it belongs in my bio. The sticky point, as you say, is how it’s used. Are you a mom who writes, or a writer who has children?

I think the pejorative comes into play when the context is skewed: When the thing under discussion is your writing (say, in a review or interview), the motherhood piece should be secondary. When I’m in settings that revolve around our family and schools, the mom role takes center stage, and appropriately so. The discord comes in for me when motherhood is stressed disproportionately or out of context. An example: Shortly after my book came out I was being interviewed for an evening news-magazine type program. I’d talked to the reporter on camera at length about the novel process, the book’s inspiration, the writing life. Yet when they went to shoot B-roll footage at my house, they kept asking me to push my youngest child on the swing and dole out snacks in the kitchen.

I think the pejorative comes into play when the context is skewed: When the thing under discussion is your writing (say, in a review or interview), the motherhood piece should be secondary. When I’m in settings that revolve around our family and schools, the mom role takes center stage, and appropriately so. The discord comes in for me when motherhood is stressed disproportionately or out of context. An example: Shortly after my book came out I was being interviewed for an evening news-magazine type program. I’d talked to the reporter on camera at length about the novel process, the book’s inspiration, the writing life. Yet when they went to shoot B-roll footage at my house, they kept asking me to push my youngest child on the swing and dole out snacks in the kitchen.

Thankfully, when the three-minute segment aired, there was very little of that, and the piece didn’t lead with those images. We both know it could have easily been otherwise, and often is.

One last thing: I’ve always found it interesting that the reaction so many people have to my being a writer as a mom of five is, That’s so amazing you kept it up. As if it’s as some kind of noble or very disciplined act. Which I can understand; mothering in itself is a huge and absorbing thing, regardless of how many children you have. But the truth is, it doesn’t feel noble or disciplined to make time to write. Writing is the one thing I’ve always done and always wanted to do, and it would actually be noble and disciplined if I had to give it up. That sounds precious and pretentious so I don’t usually try to explain that, but it’s the truth. Amid all the things that have had to fall by the wayside in the triage of taking care of a large family, writing has been the non-negotiable thing. I can’t overstate the value of finding a tribe of colleagues and friends like you who feel the way I do about writing. It has quite simply expanded my notion of home.

Oh, I so agree about writing being anything but the “noble and disciplined part.” When I started to write seriously, my kids were thirteen, ten, and six, and every moment of writing felt like a guilty pleasure. Not that I haven’t had my share of writing struggles, but there’s no question it still seems more like a privilege than like a chore.

Before signing off here, I do want to thank you, Nichole. I have a feeling that when you sent me that very first note, offering to mention my book, you did a lot more than you may have imagined. It was almost like you were a welcoming committee: Welcome To Being An Author! It was such an incredible source of light as I stumbled through the darkness of review anxieties and terrors about sales numbers.

It’s been a real gift to be your colleague and your friend—and a real pleasure, too, to talk to you here.