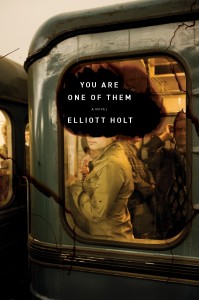

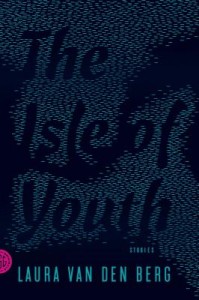

Back in May, my good friend Laura van den Berg interviewed me for Fiction Writers Review when my first novel, You Are One of Them, was published by Penguin. Now that her second story collection, The Isle of Youth, is out this week from Farrar, Straus and Giroux, I got to be the interviewer.

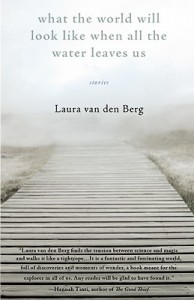

Before Laura and I met, we were already smitten with one another’s work. I worked at One Story magazine when they published the title story of her first collection, What the World Will Look Like When All the Water Leaves Us (Dzanc Books, 2009), which was a Barnes & Noble “Discover Great New Writers” selection and shortlisted for the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award. She was working at Ploughshares and happened to read a story of mine in the slush pile. When we met a year or so later, we became fast friends.

Interview:

Elliott Holt: Your book’s epigraph is from Yoko Tawada’s The Naked Eye (New Directions, 2009): “I felt like I was playing a part in a movie with a plot unknown to me.” And it’s fitting since all your stories feature women who find themselves in scenarios so wild they could be movie plots. The characters include magicians, private detectives, acrobats, and a gang of robbers who commit their crimes in gorilla costumes. These women are all playing roles, and are somewhat detached from the scenes around them. The premises of the stories are vastly different (and hugely imaginative) but the characters in these stories share a similar emotional core. Where do your ideas come from? Do you start with a premise? Do you find yourself thinking, “What if a woman followed a troupe of acrobats around Paris?”

Laura van den Berg: I almost always start with voice. And by “voice” I mean that I get a line lodged in my brain that just won’t leave me.

Do those lines generally end up as the first lines of the stories?

Often, yes. With “Acrobat,” for example, I was washing dishes and all of a sudden the first line, “The day my husband left me, I followed a trio of acrobats around the city of Paris” came into my mind, seemingly from nowhere. Even though the story changed a great deal in revision, that was always the first line. Same for “Lessons” and “I Looked for You, I Called Your Name.”

So I follow those voices and they lead me through the (usually very rough) first draft. They are almost always “I” voices and they are always a woman’s voice, which probably helps explain that consistent emotional core.

What is it about writing in the first person that appeals to you?

It’s that voice thing, that “I” that wedges its ways into my imagination. Or, at least it’s that initially. In The Isle of Youth, the characters often find themselves caught between truth and deception.

Right. One of my favorite themes!

Right. One of my favorite themes!

Yes. You do it so well in You Are One of Them. The characters in my book want something true, they want something real, but they struggle to face themselves in a fundamental way. First person can be especially evocative in that kind of landscape. But you know, I rewrite first-person stories in third person all the time during revision. Just to see.

You mean you rewrite them in third person, and then put them back in first person?

Yeah, just as an exercise. I want to be sure it’s the right choice, even if I know it in my gut. And to be sure I’m not over-relying on first person, not doing it just because it’s familiar.

The “I” is an eye.

You’re exactly right: the “I” is an eye. And I love that about first. So I almost always come back to it. That “I” does keep changing—to the other characters, to themselves, perhaps even to the reader. I love that layering of perception.

Disappearance is a leitmotif in this book. There are all kinds of vanishings. How conscious of that were you when you were writing the individual stories? The last line of “Antarctica,” for example, just kills me: “I did not know if one day I would disappear and no one except a missing woman and a dead man would be able to tell the people who loved me why.” It seems like that line could apply to most of the characters in this book. All these “I”s feel like they’re in danger of disappearing.

With the first couple of stories, I was doing it unconsciously, but soon I could see overlap—vanishings, doubles, mysteries, most of which remain unsolved. I love noir, and I wanted to use some of those tropes as a means of exploring self-mysteries. Who am I? Why am I doing what I’m doing? Am I, as you put it, in danger of being erased, of disappearing? An odd thing: even as a child, I’ve had an intense fear of people disappearing.

That’s so interesting because you have such a stable personal life. You have been with the same man (the immensely talented fiction writer Paul Yoon) for years and you have this really tight-knit group of friends. Do you think your steadfastness and loyalty are the result of your fear of losing people?

Quite possibly. I have no real concrete reason to have that fear (i.e., no one in my family has ever gone missing), but it’s always been a very present fear for me, for reasons I don’t fully understand, which is probably why I write toward it.

I love the fact that sand turns up in two of your stories in this book. First, there’s this startling scene in “I Looked For You, I Called Your Name”:

I opened my mouth and started packing it with fistfuls of damp sand. The grains scratched the roof of my mouth and got wedged between my teeth. Grit ran down the back of my throat. My cheeks ballooned; sand stuck to my gums. It became difficult to breathe. I imagined my body filling up as an hourglass…

That hourglass image is killer. And then, in “The Greatest Escape,” there is this: “Before shows, my mother always dusted me with glitter, which left behind a fine gold grit. My skin felt like it was coated in sand.” And I was thinking that sand is an amazing image because these characters all have grit, in the emotional sense, but they are also so aware of the fact that they don’t fit smoothly into the world. They have rough surfaces.

I’m sure those images came to you intuitively, but they’re so lovely and work so well, in a thematic sense.

Oh, thank you! I’m so glad you liked that moment from “I Looked For You…” It took me so long to discover that action—I kept writing and re-writing, trying different things. I do see the women in Isle as being tough. Fighters, survivors. But also very searching and vulnerable at the same time.

I was painfully shy as a child and had very few friends until I hit my early/mid twenties (probably another reason why I treasure my friends now). So I have been there, in that loneliness and detachment. Writing was really the thing that saved me from that detachment, that lifted me out.

I know that you’re almost done with your first novel, but you took breaks from working on it to write the stories in this book, right?

I know that you’re almost done with your first novel, but you took breaks from working on it to write the stories in this book, right?

That’s right about the novel. I started it in 2008 or 2009.

Did you feel like you were cheating on the novel when you wrote these stories? Did writing stories feel like a vacation?

Ha! I don’t think I felt that guilty. I think it was more like my novel was a spouse I got really mad at and then we decided to separate for a bit and I had a few flings. And they did feel like a vacation, partly because it felt great to finish something and also because the form was familiar. The novel is such a radically different form. But of course the stories were also hard in their own way, as most things in writing tend to be.

How do you decide how to order the stories in a collection?

I have a great story about this: In May of 2012, a notice was slipped under our apartment door, in Baltimore, letting us know major construction was to be happening on our floor. It’s a long story, but there was a part of our building that had to be reached through our bedroom closet (!), so we had to empty it out and consent to having people traipsing through our apartment at odd hours for three weeks. Dust everywhere, lots of noise. I was perhaps even more annoyed about this because I had set aside that block of time to organize my collection.

So I was lamenting this on Facebook and a friend who was moving let me know that his and his girlfriend’s apartment would be vacant soon, as they were leaving a bit before their lease was up. And they very kindly offered the place to me to work. So I had this empty apartment, just a chair and a small table. No WiFi. I spread out the book page by page. I made lists of the first and last lines and tacked them to the wall. The process became very physical, like assembling a puzzle.

Some obvious things jumped out, like putting the one third-person story in the middle, as a kind of transitioning device, and spacing out the two stories with missing fathers. But the physicality of the process also allowed me to notice smaller things. Like how the last line of the first story has the word “evidence,” which bled into “Opa-Locka,” the second story, which is about private eyes.

The first and last story bookend with arrivals and bodily danger (a hurricane, an emergency landing); the narrator has a twin that died at birth in the first story; in the last one, the narrator has a adult twin that goes missing.

It’s important for beginners to know that writers are not idiot savants. So much of the process is intuitive, but there is also a lot of conscious, strategic work. A lot of awareness of patterns, etc. You have to have perspective on your own work. A critical eye.

I agree. All that work is not done by elves. There is a lot of labor involved.

To me, a collection is a chance to not only gather up stories, but to create a world. Even though the situations and locations are varied, I feel like all the characters kind of exist in the same fictional universe, if that makes sense.

It’s hard to make collections work. The best stories work as individual gems, but putting them together in a book is its own challenge. Are there story collections that you return to regularly? Ones that work particularly well?

Oh, so many: Like You’d Understand, Anyway,” by Jim Shepard (Knopf, 2007); Like Life, by Lorrie Moore (Knopf, 1990); Reasons to Live, by Amy Hempel (Knopf, 1985); and Escapes, by Joy Williams (Atlantic Monthly Press, 1990). And After the Quake, by Murakami (Knopf, 2002), is another huge touchstone. I think it’s his best book, in fact.

I agree: that’s my favorite Murakami. I like that book better than his novels. I hadn’t really thought about it before, but your fictional worlds can be compared to Murakami’s.

I am also wild for Battleborn (Riverhead, 2012).

I am also wild for Battleborn (Riverhead, 2012).

Oh, man, Battleborn blew me away. Claire Vaye Watkins is so good. And so is Karen Russell. And Jamie Quatro. And Ramona Ausubel. And Lauren Groff. I love seeing all these young women writing such amazing stories. And you, of course.

Oh, yes! I am a massive Karen Russell fan. Alice Munro, of course. All the amazing women you mentioned. The list is just endless. I love your stories, though I think you’ve said they take you a long time?

I write first drafts really quickly, but then have to mull over them for a long time, to figure out what they’re really about. And then I revise so much. It usually takes me three years between a first draft and a finished draft of a twenty-page story. That is too slow!

“Evacuation Instructions” is my favorite of yours, I think. I am prepared to wait very patiently for your collection.

I’m working on nothing but short fiction for the next year. Speaking of working, do you listen to music while you write? Do you write at night or in the morning? I imagine that you and Paul work at very different times of day, but maybe I’m wrong.

Yes, I do listen to music. And ideally I work in the morning, but I’ve learned to work in transit too, like on the commuter train, where I get a lot done. There I really need the music as a focusing agent. Once I stop hearing the music, I know I’m rolling.

Yes, writing on trains is so great. I think there should be a train residency. Just devote a whole Amtrak car to writers. Let them go up and down the Northeast Corridor, scribbling.

I feel sort of bereft if I’m not working on something, so I really take it everywhere, if only in a small way.

Speaking of traveling, one of the things that impresses me about your work is the way you set stories in places you’ve never been. Before I met you, I fell in love with your story “What the World Will Look Like When All the Water Leaves Us,” which is set in Madagascar, and I was sure that you had actually been to Madagascar. But you haven’t. And the stories in this book are set in far-flung places like Antarctica and Patagonia. How do you do research? You haven’t been to Patagonia or Antarctica, have you?

No, I haven’t. Though I would like to. I love travel. When I need to research a place, the first—and often only—thing I do is buy a travel guide, preferably Lonely Planet. I can remember rooting around in the travel section of Politics & Prose for a guide on Antarctica. I research by preparing I am going away on a very long trip. What will I need to know? I like just enough fact to guide and inspire, but I don’t like to get too cluttered with it.

And the places in your work often function symbolically. I mean, in “Antarctica,” Lee goes there to find out about the explosion that killed her estranged brother while he was working at a Brazilian research station there. So the chilly, otherworldly quality of the setting underscores the distance between the siblings. And Lee is so alienated from the place that we don’t see it that closely. It works as a slightly abstract location, if that makes sense.

Exactly. I have been trying for years to write a story about Antarctica, but the narrator was always a researcher there and I knew my grasp of fact was too loose. I needed that outsider perspective. And also the anchor of Cambridge, which is very familiar to me.

Exactly. I have been trying for years to write a story about Antarctica, but the narrator was always a researcher there and I knew my grasp of fact was too loose. I needed that outsider perspective. And also the anchor of Cambridge, which is very familiar to me.

Right. Florida and Boston (two places you know well) appear in several stories.

They do. This is the first time I have ever written about Florida, but even then it’s not Central Florida, where I’m from, but south Florida, which always had a kind of mystique to me as a kid.

You and Karen Russell are both from Florida. And Lauren Groff lives there. Perhaps it’s fertile ground for fiction writers.

And both Lindsay Hunter and Tao Lin, who published books this year (Don’t Kiss Me and Taipei) that I loved, spent formative time in Central Florida. From the swamp we rise…

I did a residency in Key West this summer and, man, what an amazing and strange place. My housing was haunted, as was the person’s next to me. We had to “cast out” the ghost at one point. I am not at all kidding. It was a serious problem.

What? How did the ghost haunt you? I mean, what were the signs? And what did you do to “cast out” the ghost?

Oh, boy. This is a long story. There were the most insane sounds at night, between about 2am and 5am—whispering, laughter, footsteps. But outside there was nothing. After about two weeks, I discovered that the painter next door was hearing the same thing and thought she was losing her mind.

People say Yaddo is haunted and I really wanted to see or hear a ghost when I was there. But nada. I was disappointed. I wanted a good story.

As it turned out, another artist there has psychics in his family and is versed in this stuff. So with his help, we did a ritual where we rang a bell in every corner of every room in our houses and asked the ghost to leave. Then we spread salt all over the thresholds and windows. And we never heard a peep again!

I think it’s good for artists and writers to embrace the weird. I want to believe in ghosts and psychics but maybe I don’t really. Maybe you have to believe in them to hear them…?

I only kind of half-do, but the Key West situation tilted me toward “do for sure.” It was nuts. Florida seemed dull to me as a kid. Now I wonder what that kid-me was thinking. It took me a while to see the deep strangeness.

Here’s a question for you: what do you think the hardest part of writing a book is?

Oh, interesting. For me, it’s definitely the self-doubt. If I believed in myself more, I’d work faster. What about for you?

Self-doubt for sure. For me, that can only be quelled by writing. When I’m the most anxious, I write almost frantically, as though I am trying to write my way out of something, which I suppose I am. I think also this, from the ever-wise George Saunders:

The biggest obstacle I’ve encountered (and one I am still encountering) is that I have a tendency to want to coast. That is, to show up in the morning and sort of go on auto-pilot, being very sure of myself and my project, without being willing to really dive in, change course, find some new energy in the story, reject what I think I know about it. That’s an ongoing challenge, I think. And not just in writing.

I love that. To resist coasting, falling back on what you already know how to do, pushing yourself in the right ways, is always a huge challenge.

That’s very well put. Yes. I also write a lot when I’m anxious—but often, I write these fragments or scenes that I don’t know what to do with. I write best when I’m not worried about what it is I’m writing. I just follow the sound and the flow, you know?

Absolutely yes. It’s the best feeling. Getting lost in it.

I need to try to maintain that freedom, that sense of play, every day. But sometimes I feel too much pressure to play.

Yes—I think I got frozen up with the novel at times because I was focusing too much on the idea of writing a NOVEL, a BOOK.

Exactly. I get caught up in the idea of the project or the product. Instead of just living inside the sentences. The sense of play is so important. It gives the work vitality and mystery and energy.

I threw out maybe 80% of what I had and started over this year. When I tell people that they are like, “Oh, no! How awful!” But I was actually thrilled. I was playing again.

And it is harder to keep that sense of play going with a novel. With stories, you get to start over more often, with new situations and characters and worlds. And it’s fun.

That’s right. And if you write fifteen pages and you lose interest and toss them out, no biggie! With 100 pages, it seems more dire.

Totally. The stakes felt much higher while I was writing a novel. But I think the writing in my stories is better.

Totally. The stakes felt much higher while I was writing a novel. But I think the writing in my stories is better.

I can’t wait to read your next story.

Hey, one more thing: how does it feel to be off Twitter?

It feels really good to be off Twitter. Twitter was fun for a while, but I was really sick of being known for Twitter. I just want to hide at my desk and work on my stories.

I can 100% understand that. I mean, I loved your Twitter story, but you wrote a whole damn novel! Like a real book!

But it’s fascinating to see the way our sense of identity changes online. Technology is changing the way we see ourselves and others. It makes for interesting possibilities for fiction.

It’s that ever-shifting “I” again.