I’d known Lisa for many years through our work at Boston’s GrubStreet, where she was and is still considered the “novel guru” and where she instituted the now ever-present Novel-in-Progress courses, a way of teaching the novel that avoids heavy reading loads and fierce workshopping during the jittery months and years of beginning a novel. Lisa was also the one with the mean sense of style and stellar glasses. But this was the Lisa I knew only in passing through the halls and at parties. It was when Grub’s artistic director, Chris Castellani, decided that Lisa and I should join forces to teach the Novel Incubator, a year-long MFA-level course in the novel, that I found out how truly devoted Lisa is to her students and to the idea of the novel as a whole.

When Lisa was forced to leave the Novel Incubator due to time commitments and other strains and give her all to the final revisions and publicity for her second novel, I couldn’t say I wasn’t disappointed. But I also knew that Lisa was doing what she needed to keep her writing career a priority. I got a chance to read her book, The Fifty-First State (Engine Books, 2013), several months before it came out. Though I’d read her first novel, and heard her espouse many nays and yeahs about novel craft, it wasn’t until I got to sink my teeth into the new book that so much of her talent crystalized for me. It’s the small details that she nails, the voice—especially when writing about her teenaged male protagonist—and her sense of the most subtle moments of drama.

Interview

Michelle Hoover: For two years we taught Grub’s Novel Incubator, and despite the long hours and reams of paper, I believe we both considered it one of the best teaching experiences we ever had. With each novel submission, I felt the writer had handed me their first child—gorgeous, naked, and screaming—and I was determined to do my damnedest not to drop the thing on its head. The process felt really important.

Lisa Borders: I agree that the process felt important, and very different from helping students revise their manuscripts in other classes I’ve taught. Reading two drafts of each student’s novel in one year was so immersive and all-consuming – in the best possible way. It created a kind of bonding that allowed for a great deal of trust, and I think that helped the students to re-envision – in some cases, radically so – their novels.

One thing I didn’t quite appreciate going in was how intense the program would be for the students, many of whom were working full-time jobs while in the Incubator. Some of them definitely had moments of doubt as to whether they could finish their revisions. But we helped them through it, and I rather enjoyed wearing the “writing therapist” hat on occasion! I always recognized myself, how hard I often am on myself, in their doubts.

When I first moved to Boston, I knew only one or two people, so when I heard about Grub, I found myself hanging around the place like a stalker. The fact that I was able to make so many friendships so quickly in a city that isn’t famous for its cheeriness is due to Grub. And I can’t help but think my writing career might have gone the way of so many post-MFAers if I didn’t have Grubbies for support and connections. But you’ve been involved with Grub from the very beginning. It must be even more significant to you.

Even though I’m extroverted by nature, I was bullied as a kid, which turned me into a somewhat guarded adolescent and young adult. I developed a veneer that allowed me to become friendly with a variety of people, but there were only a handful I felt really close to, and even then, I didn’t always feel like my close friends “got” me; it was more like we mutually enjoyed and cared for each other, but didn’t completely understand each other. When I went to grad school, I thought I’d find my people in my creative writing program, but while I made a number of lasting friendships, I still didn’t feel, by and large, like I truly fit in.

Even though I’m extroverted by nature, I was bullied as a kid, which turned me into a somewhat guarded adolescent and young adult. I developed a veneer that allowed me to become friendly with a variety of people, but there were only a handful I felt really close to, and even then, I didn’t always feel like my close friends “got” me; it was more like we mutually enjoyed and cared for each other, but didn’t completely understand each other. When I went to grad school, I thought I’d find my people in my creative writing program, but while I made a number of lasting friendships, I still didn’t feel, by and large, like I truly fit in.

I remember the moment when I realized I’d found what I was looking for in Grub. It was about ten years ago. Chris Castellani was looking for people to play on the Grub Street softball team, and tried to recruit me.

“I can’t play softball, Chris,” I said. “I was picked last for every team in grammar school.”

“Lisa, we’re a bunch of writers,” Chris said. “We were all picked last!”

It was just an offhand comment, but it really altered the way I looked at things. I realized then that I was part of something, a wonderful Island of Misfit Toys, and I could relax and be myself.

We’re all wonderfully odd. Grub seems to attract the truly dedicated and persistent, no matter how long a project might take for a writer to grab hold of.

One of the things I loved about teaching the Incubator was getting that window into other people’s minds: beautiful, complex, or sometimes – to borrow your phrase – wonderfully odd. I’m not a religious or mystical person, but it did, at times, feel to me like touching another’s soul.

There are a lot of teachers in the writing world who seem to believe that novel writing is unteachable, that it is simply too mysterious, too precious. And it is. But so too is the short story, so too the poem, the essay.

We were both working on our second novels when we started the Incubator. I felt I at least could see problems and find fixes after all my teaching, though that didn’t make the process any less surprising. When I wrote my first book, I had read novels aplenty, but I still didn’t understand how to craft one. I wrote the first draft as linked stories, because the scope of a novel was so foreign. It wasn’t until I started working with one novelist after the other that the form and all its possibilities gained shape for me, and I grew to love it even more. Did you find the process the same?

My first novel was originally conceived as linked short stories as well, and I felt the same limitations in terms of scope – that is, being able to envision the totality of a novel. I’d had a professor in grad school tell me he thought I was a “natural novelist,” and that I’d eventually gravitate to that form, but since our program emphasized short stories – as so many MFA programs do – I really had no idea how to go about writing a novel.

In his book Writing that Makes a Difference, Philip Gerard discusses that one of the differences between novels and short stories, apart from simple length is subject:

“The novel is the cathedral of great subjects, which, like a mountain, makes its own weather through effects of scale; indeed, it can support issues and subjects that would overwhelm a short story…. All novelists are really novelists of manners: They chronicle the interaction between the private soul and the public society. Their characters are connected to time, history, politics, culture, things often missing in short stories, which may be more prone to tune into private, self-referential subject matter, since the story is a more lyrical form, the novel by definition a more prosaic one” (184-185).

I disagree about limiting the lyrical form here to the short story, but he’s got something when he links the novel to both the individual and the wider world. This is often something I find myself grappling with when responding to student novels, the need to push them to something larger, to grow that “aboutness,” and to think of their subject within a larger context, particularly one that deserves revisiting and rethinking. Just the other day, a woman was excitedly explaining to me the subject of her novel, and while I was nodding my head, I couldn’t help but think: That’s not a novel.

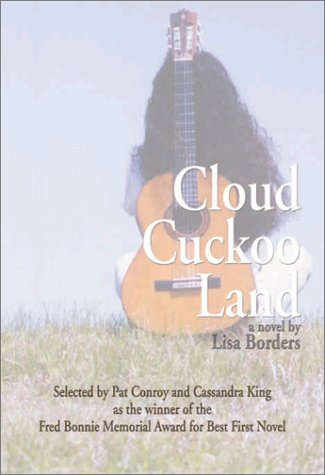

Definitely. Or the one where the first chapter of a student’s novel reads too much like a short story: rather than opening outward to invite a larger story to unfold, the tale seems to be finished at the end of that first chapter. In his essay “An Architecture of Light,” Gerard also talks about this phenomenon of the novel being larger than the short story. Not just longer, but larger in scope, theme, ambition. I think for me, the move from short stories to novels did have to do with that desire to tell a larger story. Cloud Cuckoo Land, my first novel, grew from a failed short story that was, indeed, large in its subject and ambitions. But I had no idea of how to approach writing it, and once I shifted from the idea of linked stories to the concept of a novel, it felt very unwieldy to me. The first draft was over 500 pages. I didn’t have an outline, and because it spanned about 15 years I found it difficult, at times, to keep track of what was happening, and what needed to happen. I eventually created a timeline, which was my way of tricking myself into doing an outline.

When I conceived of my second novel, I had a stronger idea of what a novel was, and it felt less difficult to hold the book in my head – to conceive of it in its totality – than it had with the first novel.

I also wanted to simplify the book structurally, and I thought that having it span only one year (as opposed to fifteen) would be less overwhelming. However, I also created (using an outline, this time) a more complicated plot than my first novel had, with multiple subplots and multiple points of view. I ended up with a first draft that was over 800 pages long! So much for simplicity.

Eight hundred pages! I know I wrote eight hundred in the process, but my drafts were more minimal, and I constantly had to go back inside to deepen them. Burrowing in—that’s what I call it when I talk to my students. We’re so used to speed these days, to surfaces that pretend to be something deeper. It’s difficult to just make yourself stay still and quiet and dig and dig. But that’s what a novelist does. That’s what most successful writers do, really. And that’s what I love most about writing—that stillness in the midst of all the push and shove. Still, it takes work for me to stretch out a moment, and I can’t help but wonder if this comes from my more reticent, Midwestern self.

Eight hundred pages! I know I wrote eight hundred in the process, but my drafts were more minimal, and I constantly had to go back inside to deepen them. Burrowing in—that’s what I call it when I talk to my students. We’re so used to speed these days, to surfaces that pretend to be something deeper. It’s difficult to just make yourself stay still and quiet and dig and dig. But that’s what a novelist does. That’s what most successful writers do, really. And that’s what I love most about writing—that stillness in the midst of all the push and shove. Still, it takes work for me to stretch out a moment, and I can’t help but wonder if this comes from my more reticent, Midwestern self.

But you, you seemed to work in the opposite way. Having both of us in that room, I think it helped us approach the different ways our students worked as well.

It was a bit of a revelation to me, as we worked with our students, to see that they mostly fell into those two camps: the overly-long, messy first draft that needs to be pared down; and the skeletal first draft that needs to be fleshed out. Both of my novels came out as behemoth, everything-but-the-kitchen sink drafts, and I’m resigned to the fact that that’s my process.

I don’t know how much of this is geography or temperament – am I more prone to examine the minutiae of a moment in detail because I’m a neurotic Northeasterner? I remember that feeling, as a kid, of time moving slowly in certain situations – when I was in sixth grade, in the far outfield during a softball game and trying to find ways to amuse myself; or in the fourth grade, when my father died. I’ve always been interested in the perceived movement of time in certain life situations, and as a result, I’m interested in how it moves in the novel. One novel that I want to re-examine in this regard is Elizabeth Strout’s Amy and Isabelle. The way time moves in that book is a bit mysterious to me; it makes a profound emotional sense, and yet, it must have been incredibly difficult to map out structurally.

For the same reasons, I recently took apart Jim Crace’s Being Dead for a Bread Loaf lecture on structure. I often teach structure, but I wanted to do so in light of a book that seemed to challenge our usual assumptions about how time and structure function in a novel. It was a revelation to witness how Crace is using many of the same conventions, but coming at it from so many different angles that the effect becomes operatic.

Having mentioned my dad’s death leads me to a question I’ve always been curious about. I know that you lost your father when you were young as well – in your case, I think you were fourteen? I was nine. I feel that my father’s death led to a degree of introspection and a need to examine minutiae that turned me into a writer. I’m not entirely sure I would have become a novelist if I hadn’t had that experience. Do you feel that way, too? Or do the experiences feel completely separate to you?

Absolutely. Isn’t “writers with unhappy childhoods” a cliché by now? Mine was otherwise pretty happy, but there were a few other “unusual” moments that certainly make me who I am today.

I guess I’m being pretty vague. My characters are equally discreet. They don’t talk about their emotions much, and certainly don’t dwell. In my upbringing, doing so was considered immodest and self-aggrandizing, though I’ve personally come to appreciate the openness more commonly expected in the East. Part of my burrowing-in involves revealing my characters through silences, landscape, and work, of breaking through that restraint that is more instinctual to me. Surprisingly, though, I’m finding that my family of characters in my second novel wear their feelings a little more on their sleeves.

I guess I’m being pretty vague. My characters are equally discreet. They don’t talk about their emotions much, and certainly don’t dwell. In my upbringing, doing so was considered immodest and self-aggrandizing, though I’ve personally come to appreciate the openness more commonly expected in the East. Part of my burrowing-in involves revealing my characters through silences, landscape, and work, of breaking through that restraint that is more instinctual to me. Surprisingly, though, I’m finding that my family of characters in my second novel wear their feelings a little more on their sleeves.

Your second book also explores different forms of grieving. Is this drawn from personal experience? Did you do any research into the psychological states of your characters?

When I started writing The Fifty-First State, grief was a somewhat distant emotion yet ever-present emotion, following my dad’s death. Despite the fact that I hadn’t experienced any other significant losses between his death and the early work I did on this novel in 2001, I thought I was still connected enough to grief that I could write convincingly about it.

In 2002, shortly before my first novel was published, one of my closest friends, Barbara Durkin, died suddenly and unexpectedly at the age of 40. After her death, someone close to me died every year for the next few years: my mentor from graduate school, my uncle, my aunt, a cousin who felt more like a sister. At first I was reeling and couldn’t write at all, but once I got back to work on the novel I realized I had new insights on grief, new textures I could incorporate into the book.

Despite having been on the frontlines of grief for those years, I still ended up having to do some psychological research into my character Hallie, who represses emotion. I needed to figure out how someone who is so emotionally repressed would process grief, and what it might take to break her out of her state of denial.

But that’s what made Hallie so real to me. She seemed to process her grief the way I usually do my own. I think others generally misjudge people like that, find them off-putting. I know you had to work some to make Hallie more likable, but she seemed just fine to me.

That raises the question of the “unlikable” female character, doesn’t it? I never found Hallie unlikable, even when she was at her most prickly in early drafts. I knew her heart, and hopefully as the book unfolds the reader gets to know that heart, too. Since I’d never thought of her as unlikable, I didn’t mind “sanding her rough edges” – as our wonderful mutual agent put it – to allow her to come across the way I really saw her.

All of that said, I bristle at the notion that female characters have to be likable. I love what Claire Messud had to say on this subject, in a Publisher’s Weekly interview, when asked if she’d want to be friends with her character, Nora:

“Would you want to be friends with Humbert Humbert? Would you want to be friends with Mickey Sabbath? Saleem Sinai? Hamlet? Krapp? Oedipus? Oscar Wao? Antigone? Raskolnikov? Any of the characters in The Corrections? Any of the characters in Infinite Jest? Any of the characters in anything Pynchon has ever written? Or Martin Amis? Or Orhan Pamuk? Or Alice Munro, for that matter? If you’re reading to find friends, you’re in deep trouble. We read to find life, in all its possibilities. The relevant question isn’t “is this a potential friend for me?” but “is this character alive?”’

You must have run into some of this with The Quickening.

I adore a good nasty character. They give a lot of energy to a book. But as Messud seems to be putting her finger on, women have a harder time getting away with it—we’re still supposed to be the gentler sex.

I do think it’s important for a writer to find compassion for their characters, to try to understand the very human reasons that take a person to the brink—doing so seems simple character development—but it’s also important to let the character make mistakes when at that brink, to do bad things. A writer doesn’t have to condone their characters’ actions, but they should spend time understanding how they got there.

You’re already out of the woods, so to speak, when it comes to The Fifty First State—it’s launched, publicized, toured, and come home again. I know I’ve been knocking around a few ideas for my next book—from a late 19th century ghost story to character piece about a famous Harvard criminologist. What about you?

I have two projects I’m working on. One is a novel composed of three novellas set in and around the Boston music scene in the past decade (though, since one of the characters managed a band that almost made it in the 80s, there’s a lot of back reference to the golden age of alternative rock). The other is also a novel, about a middle-aged veterinary technician who, fed up with her life, leaves New England for Florida, where she gets a job in a primate sanctuary. There, she meets two people who become like family: a transgender teenager, and an elderly man who may have a violent criminal past. I’m tinkering with both projects, but I think I’ll end up writing the series of novellas first, since I’ve already written one, and since the other book requires some research.

Ah, but research is the best part! But just ignore me. The music scene. That sounds right down your alley.

The novellas feel more accessible to me at the moment, but I do love research. To write the other book, I’ll need to spend some time in a primate sanctuary – which is something I’ve always wanted to do! Writing a novel is the best excuse imaginable to investigate a subject you’re curious about, isn’t it?