As the final book in the Magicians Trilogy, The Magician’s Land (Viking) took time for me to savor. Reading it was like catching up with an old friend who visits from out of town, knowing that friend will go away soon, possibly forever, and talking to them well into the night to slowly let them go. Some trilogies race to the finish, but even as the plot of The Magician’s Land urged me forward, I read passages of this book and reread them, then bought the audiobook and listened to those passages again as Lev Grossman moved his main character, Quentin Coldwater, into a future that I could no longer follow after the last page. Grossman is aware of the conflicting desires of reading and the effect reading fantasy literature has on our lives, because, as his character notes, “that was one thing about books, once you read them they couldn’t be unread.” After spending so much time with the characters in worlds of the Magicians Trilogy, I had a hard time letting them go. This is meta-fantasy at its best.

This final novel follows Quentin and his friends’ last effort to save the magical land of Fillory— which sits on the brink of an apocalypse—and it does so with maturity on every level of storytelling, making it one of Grossman’s most sophisticated stories to date. The plot picks up after Quentin’s banishment from Fillory and subsequent return to earth. Quentin determines to move on, but instead of adventuring in a magical world he uncovers new adventures in his old haunts on earth. Quentin acquires a teaching position at Brakebills School for Magical Pedagogy, transforms into a blue whale to visit Brakebills South, and even participates in a high stakes heist on a magic carpet. Throughout this narrative, the story revisits magical landscapes with familiar characters, but Grossman casts those landscapes in a new light. He peels back the layers of each world and lets characters see beneath its magical veneer, causing characters to view their worlds from a new, more mature angle through the experience. Exploring the depth of these worlds as characters grow and change over time is one of the distinct pleasures of reading through the trilogy as a whole. And in this last novel, Grossman beckons us to come further up and further in.

This novel’s refreshing perspective best applies to Quentin, who must accept new roles and knowledge as a result of his experience on earth and in Fillory. Quentin discovers his true discipline during his tenure at Brakebills, because the dean requires him to go back to his former professor’s office to be retested before the start of the term. The passage of time recreates this scene in a new image because Quentin the adult is faced with the old hopes and fears of Quentin the student. The previous wonders of the school of magic become hard realities. And like Quentin, we as readers are slowly being stripped of the delusions that we once shared with him. Yet while this is a loss of sorts, it is a development that also opens the way for a richer understanding of his character and a more dynamic understanding of his world. Quentin still secretly wishes for a spectacular magical talent, but he winds up with the plainest of all abilities. What used to instill a sense mystery and pride for characters deflates on further scrutiny, creating a fantasy world that is tangible and relatable.

This novel’s refreshing perspective best applies to Quentin, who must accept new roles and knowledge as a result of his experience on earth and in Fillory. Quentin discovers his true discipline during his tenure at Brakebills, because the dean requires him to go back to his former professor’s office to be retested before the start of the term. The passage of time recreates this scene in a new image because Quentin the adult is faced with the old hopes and fears of Quentin the student. The previous wonders of the school of magic become hard realities. And like Quentin, we as readers are slowly being stripped of the delusions that we once shared with him. Yet while this is a loss of sorts, it is a development that also opens the way for a richer understanding of his character and a more dynamic understanding of his world. Quentin still secretly wishes for a spectacular magical talent, but he winds up with the plainest of all abilities. What used to instill a sense mystery and pride for characters deflates on further scrutiny, creating a fantasy world that is tangible and relatable.

Reality and fantasy further intertwine through most of Quentin’s actions, and this approach triumphs in the quiet moments of the book. Quentin ransacks his late father’s office looking for a secret magical inheritance and finds cryptic notecards that prove to be golf scorecards rather than hidden magic texts. These are flashes of the old, endearing Quentin of the previous novels, the one who searched the back of a liquor cabinet in the hope of finding the entrance to a magic land. Remembering the younger Quentin, then, becomes an integral part of reading the trilogy, because the evolution of his character compels us to grow up with him and to continually reprocess the past. It is through this simultaneous act of memory and discovery that we are reminded why we love Quentin. Not just because he reminds us of ourselves in all his stubbornness and selfishness, but more importantly because his thirst for transportation out of the ordinary through magic is why we read fantasy in the first place. Fantasy literature gives us hope that there is more to the world than just what’s on the surface and that we can be our own heroes in it. The book thrives on the mixture of magic and the mundane, and Quentin’s joy in magic and disappointment in reality is palpable.

However, Quentin’s disappointment forces him to face his demons, figuratively and literally, and Grossman uses allusions to previous works of literature to achieve that end. Grossman often winks at other works of fantasy in clever references sprinkled throughout the three books, but his references to Shakespeare illuminate that some of our culture’s oldest stories make little distinction in terms of audience or genre. Classic works of literature incorporate spirits, demons, and magicians that appeal to adults as much as to children, and Grossman situates his mature work firmly in that older tradition. The parallels to Shakespeare’s The Tempest appear more often in this book, though they harken all the way back to the epigraph of the first novel, The Magicians, which begins with these lines spoken by Prospero:

I’ll break my staff,

Bury it certain fathoms in the earth,

And deeper than did ever plummet sound

I’ll drown my book.

By the third novel the narrator or other characters often liken Quentin to Prospero, and at one point Quentin quite literally echoes this critical act of Prospero’s: “He picked up his staff, his lovely black wood and silver staff. It took five tries, whacking it against the brick pillars in the workroom, but he broke it in the middle and twisted apart the two halves.” This is a poignant moment in the text, because he breaks the staff in order to free his former girlfriend, Alice, from a magician’s land he created. He acts selflessly to destroy his land, and this decision mirrors Prospero’s not only to serve as a lovely intertextual connection between the two tales, but as way of illuminating even more fully what it takes to wield power, as both a magician and a man. Acceptance and an ability to let go of his desires signals Quentin’s true mastery. This revelation of character also cleverly factors into the plot and Quentin’s final decision in the wake of his beloved Fillory’s near destruction.

The narrative has also matured with Quentin, who is no longer the only viewpoint character. Many early ancillary characters such as Eliot and Janet share the narrative space, in part as a necessity of the plot but also as a way to show how Quentin’s story is part of a larger whole. As Eliot and Janet face the end of the world in Fillory, Quentin and his former student and now ally, Plum, take on a series of enterprises that bring them both back to the magical world and it’s unfinished business. Where the first novel limited itself to Quentin’s point of view and then in the second incorporated a sprinkling of Julia’s viewpoint, the third utilizes several viewpoints and transitions between them intelligently. Quentin’s own growing self-awareness in adulthood creates new space in the narrative for other characters to share their stories, whether through the narrator or in scene. The narrator also demonstrates this maturity in the depth of each new viewpoint. Eliot and Janet evolve from brash and bickering sidekicks into fully realized, complex heroes in their own right. Watching the narrative transform them and make them relatable and knowable is perhaps Grossman’s greatest achievement in craft.

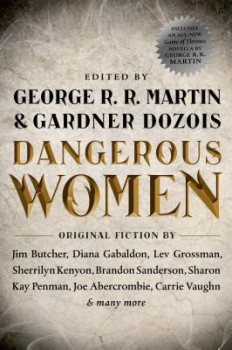

Joining those viewpoints is a new character, Plum, whose expulsion from Brakebills thrusts her into a more dangerous magical world with Quentin. Introduced in Grossman’s short story “The Girl in the Mirror” in the collection Dangerous Women (Tor Books), edited by George R.R. Martin and Gardner Dozois, Plum in The Magician’s Land struggles to accept other people’s stories as a part of her own. After the heist, she glimpses the larger picture of how a storybook world has brought her into the path of Quentin and Fillory’s stories. She realizes that “everywhere she looked things were getting connected up, or rather it was clear that they were already connected in ways that she was only now picking up on… Everybody else was deep into their own stories, and all the stories were woven together just beneath the surface.” The trilogy’s stories intersect in Plum’s life much in the same way as they do for the reader. The trilogy builds on the stories that came before it, and the knowledge that fantasy readers bring to the text with them enriches the experience of reading these books. Just as Plum’s past is a key in unlocking the final mysteries of Fillory, our past reading is a way to unlock the rich, interwoven series of stories built on the overarching storyline of the trilogy itself.

Joining those viewpoints is a new character, Plum, whose expulsion from Brakebills thrusts her into a more dangerous magical world with Quentin. Introduced in Grossman’s short story “The Girl in the Mirror” in the collection Dangerous Women (Tor Books), edited by George R.R. Martin and Gardner Dozois, Plum in The Magician’s Land struggles to accept other people’s stories as a part of her own. After the heist, she glimpses the larger picture of how a storybook world has brought her into the path of Quentin and Fillory’s stories. She realizes that “everywhere she looked things were getting connected up, or rather it was clear that they were already connected in ways that she was only now picking up on… Everybody else was deep into their own stories, and all the stories were woven together just beneath the surface.” The trilogy’s stories intersect in Plum’s life much in the same way as they do for the reader. The trilogy builds on the stories that came before it, and the knowledge that fantasy readers bring to the text with them enriches the experience of reading these books. Just as Plum’s past is a key in unlocking the final mysteries of Fillory, our past reading is a way to unlock the rich, interwoven series of stories built on the overarching storyline of the trilogy itself.

While each novel can stand on its own and conclude satisfactorily, Grossman has built a few essential worlds that help us understand fantasy and our relationship to it through through a progression of novels about people like us faced with the spectacular. This year I got to meet Grossman after one of his panels at this year’s San Diego Comic Con International. Polite and inquisitive, Grossman chatted with me for a few moments in the book signing line about our experiences in school and reading and writing fantasy. I didn’t tell him this, but my only minor pet annoyance is that almost every character in The Magician’s Land refers to Quentin, nearly thirty years old, as an old dog at some point in the narrative. I’m nearing thirty and it isn’t old, Lev, so stop that because it freaks me out to think that I, like Quentin, am nearing certain endings. Though, later it occurred to me that perhaps Grossman himself grew up while writing the novels in ways I hadn’t realized but that reflect in the maturity of the book. Because, despite what all the characters say, this final novel illustrates that Quentin at thirty isn’t old, he’s just finally old enough.