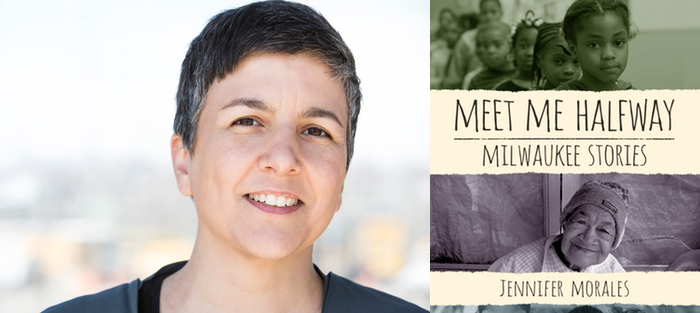

Jennifer Morales lived in Milwaukee for nearly twenty-five years, where she raised children, served in elected office, and fought alongside her neighbors in many battles over the future of the city. Jennifer is the author of Meet Me Halfway: Milwaukee Stories (University of Wisconsin Press, 2015). A collection of nine interconnected stories about life in a hyper-segregated Rust Belt city, Meet Me Halfway was recently selected as the Common Read for the incoming class at UW-Milwaukee. Jennifer serves on the boards of the Council for Wisconsin Writers and the Driftless Writing Center in Viroqua, Wisconsin, where she now lives.

Jennifer and Dasha met in Milwaukee’s vibrant writing scene, and they later crossed paths in Los Angeles, where both were enrolled in the Antioch University MFA in Creative Writing program.

Interview:

Dasha Kelly: How do you know when an idea is a story?

Jennifer Morales: Sometimes the idea decides that for me. The start of Meet Me Halfway was like that. The image of the elderly, white Mrs. Czernicki asking her black teen neighbor, Johnquell, to come over to help her move a bookcase was so powerful that I stood up from the couch, grabbed my laptop, and wrote the first nine pages in two hours.

Most ideas are more subtle. I know I have to develop an idea into a complete story when I notice I’m crushing on it. Just like a romantic crush, I find myself daydreaming about the idea, wondering what it would do in various situations, imagining possibilities for us to connect. I start looking for books on related topics in the library and bookstore, trying to cross its path. I begin to look for gaps in my near-term calendar when I can spend time with it. That’s when I know I’m hooked.

I love that comparison! It’s always rough when the story doesn’t like you back, though. Will you keep writing until the story is finished or will you release the idea if it’s too difficult to wrangle? Basically, are you the story stalker type?

I let go if it’s not working out. I definitely think there’s a point beyond which it’s not useful to push the notion, just like with a romantic crush.

Are you a story stalker?

Nope. I’m the coy one. I wait for the story that keeps winking at me, leaving me notes, showing up with flowers. I imagine the luxury of following the wisps of an idea, as soon as my fairy godmother gets around to granting my Full-Time Writer wish. As it stands now, I don’t have the time to wile and write. I don’t settle in until I know this relationship is going somewhere.

Do you tend to obligate your characters to a platform or social topic?

Whether I’m employing them as role models, cautions, or villains, they are all playing a part in the story I want to tell. I’m a political person — I can’t get away from that and therefore neither can my characters.

Whether I’m employing them as role models, cautions, or villains, they are all playing a part in the story I want to tell. I’m a political person — I can’t get away from that and therefore neither can my characters.

Meet Me Halfway is explicitly about social topics —racism, concerns of the elderly in a changing world, the discovery of sexual identity—but these questions infuse all of my work. I’m polishing up a draft right now of Junction, a novel about a lesbian divorce. In Junction, a friend gives Mat, the main character, a copy of a lesbian pulp fiction novel from the early 1950s and we end up “reading” this trashy pulp along with Mat. Without even trying, both Junction and the pulp touch on these very same issues, with characters of different races and sexual orientations interacting and growing as a result.

What are other issues and conversations you’re looking to explore through your fiction?

While I’m cleaning up Junction, I’m already flirting with (“Flirting”! Yeesh, listen how my writing work is all about building a relationship with an idea …) some thoughts for a novel about how climate change begins to shift the economy, social structures, food systems, religious beliefs, the nature of childhood, etc.

How about you? What is putting the twinkle in your eye, post-Almost Crimson (Curbside Splendor, 2015)?

I wrote a screenplay a couple of years ago, largely to see if I could write a screenplay. One of the ideas courting me at the time lent itself well to a visual medium. I enjoyed the process of sorting through a story with only the dimensions of images and dialogue. The feedback from a few filmmaker friends was wildly encouraging, but making a movie was a distant fantasy at best. So I packed the story away, in case one of these filmmaker friends chose to move on it one day. I had a new story I’d intended to develop once I finished Almost Crimson, but the protagonist from the screenplay kept sauntering by. I wasn’t done with her and her story wasn’t fully told. I look forward to fattening its bones with back story and interior dialogue. The story is about taboos. It’s about family. It’s about retribution. It’s about the oily smudge of shame. I must admit, the story and its protagonist are still a bit intimidating, but I’m looking forward to sinking into it now that the most intense travel of my tour is winding down.

Has building a writing community been helpful to your work?

It’s been enormously helpful to have a writing group. It’s a group of four women who have met in Milwaukee for a few years. In our time together, we have produced several published books, stories, and essays. I’ve gotten lots of useful big-picture and line-level advice on my various projects over the years, but the best thing for me is that we hold each other accountable for production. The group keeps me moving even if I feel stuck —I have to produce something for our next session, even if it’s a mess. We are very supportive but also honest about what we like and what we don’t think is working about a piece. Nothing is as good as settling in on the couches (in our usual spots, of course) and drinking tea and laughing about how frustrating writing and publishing can be. Nobody gets that but other writers.

Couches. Frustrations. Sessions. Tea. Sounds like much needed writers’ therapy!

It is like therapy! Writing life is hard. We need at least one person who can walk through it with us.

What’s the stubborn story/piece you keep coming back to?

One of the best things I’ve done for my own sanity was to compose a brief statement on why I do what I do. It’s short, but once I hit on it, this little observation seemed to encapsulate everything I’d written before or since: “In my writing, I wrestle with questions of gender, power, identity, complicity, and harm. Even so, I still find the world beautiful.” That’s on the front page of my website and I use variations of it in my bios and longer artist statements. No matter what I’m writing, I’m asking, What happens when different cultures and identities meet, merge, or clash? Who has the power in those interactions and what is the nature of that power? How do people harm each other and how do we know who is the harmer, the victim, the bystander? And as the child of a schizophrenic dad and an emotionally distant mother, some part of me is always asking, How do people become real? These are big, scary questions, but I always find myself leavening them with laughter and tenderness—that’s the “find the world beautiful” part of the statement.

Passion and compassion. Thank you! And you don’t have to mandate happy endings to showcase beauty inside of the scary things that go knock in our world, right?

No, not at all. There is so much beauty, as you say, inside the hard things. I was thinking the other day about the stories that emerged from the deeply ugly moment of the World Trade Center’s destruction. In particular, I was remembering a story of a person who chose to sit in the stairwell of a soon-to-crumble tower with a disabled coworker who couldn’t make it any farther. It’s horrible that both of them died, but that tiny moment of compassion and solidarity is worth writing about. It’s instructive and inspiring but it also deepens our questioning about what life means. There’s no bright sunshine at the end of that story, but there is feeling and growth in the person who hears it. Writing should do that.

Some of my stories have endings that could be considered “happy,” but for me the best ending is one in which I can see the complicated trajectory the characters have taken toward growth. Almost Crimson certainly has an ending that could be considered “happy,” but we know as readers that CeCe got to that good place by first slogging through a lot of muck—external and internal muck. She grew as a person and the reader can relate to that.

How do you show the beauty in the ugly?

I try to show construction and movement—the way things are. Deliberate lighting can depict the intricacy of a spider’s web and a wide lens can frame the choreographed emergence of dashing swallows. Similarly, writing about the way ugly is draws my attention and poetics toward, again, construction and movement. How to assemble the elements of CeCe’s conflicted emotions, for instance. How to describe the sliding distance between who she was and who she wants to become. I pour my energy into trying to capture the ugly and not hoping to clean or qualify.

When you get to the editing and refining part of writing, what do you pay the most attention to?

My friend Edward Schultz, a poet and founding director of southwestern Wisconsin’s Driftless Writing Center, loves to ask: “What’s your book about?” but he never accepts your first answer. When I told him, for example, that Junction is about the new frontier of gay divorce, he said, “No, what’s it about?” It took me three years of writing and editing, looking back through the text at various points, to say, “Oh, it’s about home. Making a home, finding a home, feeling lost and then defining your true place of belonging.” Ed then pushes further, saying, “Good, now go infuse the language with that meaning.”

That’s what my refining process looks like. Going back, thinking, “How am I talking about finding or making a home, about loss and belonging here?” and looking for opportunities to tighten that sense through word choice, rhythm, and imagery.

That sounds a wee bit terrifying, I must admit. As writers, we fuss over the words, the tone, the flow, even the syntax to shape story. Here, you and Ed are using the story to shape words. This makes perfect sense once I said it out loud and, possibly, this is what happens in our editing minds anyway. Does this line advance this story? What’s terrifying, I suppose, is the idea of slipping from “informed text” into an infomercial. Is it possible to overwhelm the language, and subsequently the story, with a banner theme?

It’s totally possible to overwhelm the story. I like your points on the spectrum, “informed text” vs. “infomercial.” I don’t think the reader of fiction or poetry wants to be “sold” anything, so we do need to be careful not to take the “Does this line advance this story?” approach too far. We can’t be robots operating unwaveringly according to some kind of prime directive. I think the point is to notice the way that, in real life, we “characters” speak and act on our values, obsessions, and driving questions—whether we can articulate them or not, they infuse our language and the places we choose to spend time.

What landscape shifts have you noticed for women in literature, either as writers or characters?

There have been some shifts? I hadn’t noticed!

OK, here is an actual shift: Although women writers are still horribly underrepresented in publishing, there has been a new wave of activism among women writers to push for change. I think about the VIDA counts of the number of published books and articles by women. Or about the Binders Full of Women Writers movement on social media. Or the Women Who Submit groups, where women writers share information on upcoming publishing deadlines and even meet in person to sit together while they send off their work.

I hadn’t noticed a shift either, but the question was asked of me recently. Yes, the social media groups and forums have been powerfully useful. I’ve been impressed with how freely the women share information and encouragement. What kind of forum or thread could you use right now?

I would love to have more guidance on the business of writing. My writing group deals with this topic on an as-needed basis: Should I pester that agent who has been sitting on my manuscript for three months? Should I agree to have my essay published in the first place that said “yes,” even if it’s not the prestigious journal I was hoping for? How much should I charge for a campus author visit?

These are essentially questions of risk and worth—two arenas women are not encouraged to be bold in. I’m grateful for my writing group, but I also am increasingly realizing how much I would benefit from an agent.

You also published your book without an agent, right? How did that go? What kinds of support do you need?

The Universe truly smiled down on us. My Almost Crimson publishing story was a classic case of degrees of separation: I’d performed in a show which exposed me to a librarian who included me on a panel where I taught alongside another poet who, a few years later, got a phone call from his publishing friend in search of fiction by a woman of color. Boom. The right door opened at the right time and Curbside Splendor has been a great partner. We rolled up our sleeves together to launch the title and I’ve enjoyed working with a team who’s also up sending emails in the middle of the night.

Planning ahead for what’s next, for Crimson and future projects, I realize that I need the support of someone who has a vantage point above the crest of the hill. I’m pretty sure this tightening in my chest is called critical mass. Or anxiety. My work and voice are relevant. I need someone who can help me broadcast both farther and wider. I’ve been introduced to two agents who, I hope, can continue expanding the reach of Crimson. I’ve also asked the Universe to send me a manager who can scout opportunities for me as a writer, a facilitator, a speaker, and a performer.

Planning ahead for what’s next, for Crimson and future projects, I realize that I need the support of someone who has a vantage point above the crest of the hill. I’m pretty sure this tightening in my chest is called critical mass. Or anxiety. My work and voice are relevant. I need someone who can help me broadcast both farther and wider. I’ve been introduced to two agents who, I hope, can continue expanding the reach of Crimson. I’ve also asked the Universe to send me a manager who can scout opportunities for me as a writer, a facilitator, a speaker, and a performer.

What do your drafts have to tell you, time and time again?

They say, “Hey, Jennifer, do you have eyes?”

Although I have sight, my first drafts always read like I was born without it. My instinctive approach to storytelling and poetry relies almost exclusively on sound, smell, touch, temperature, bodily functions, and kinetic inputs like posture and gesture. I’ll tell you that a character runs hot and that she has a tendency to touch people’s arms when she talks about a hundred pages sooner than it will occur to me to tell you that her hair is brown and curly.

I completely understand! I mean, you’ve invited the reader into your brain…can’t they see the brown hair and wobbly stair banister?

I’m so glad you get my difficulty, and I think you’ve hit upon the very source of it: that invitation inside. It’s like bringing the reader into your house. They’re sitting on the couch, so they can look around all they want, right? Check out what books you have on the shelf, notice you’re limping, hope that it’s something good you’re stirring on the stove. But they can’t have a conversation alone. They can’t know how much your feet hurt unless you tell them. Won’t eat unless you feed them.

What do your first drafts keep trying to tell you?

They tell me to take my time. I tend to err on the side of not going too long, not describing too finely, not explaining too much. Those “Midwestern” sensibilities are concerned about overstaying my welcome with the reader. With the second and subsequent drafts, I will see the many, many, many places where I need to go longer, describe more finely and explain a whole lot more. I definitely write in layers. Each draft tells me to take my time. Tell the story and take my time.