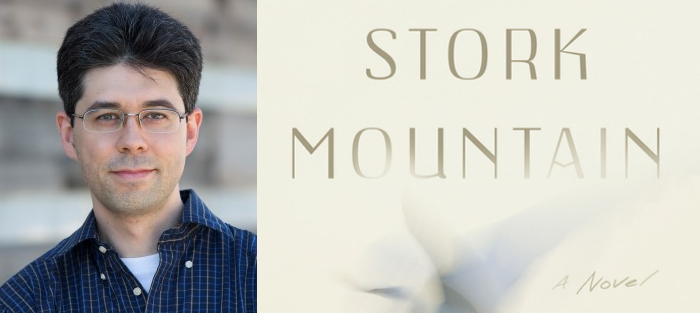

Born in Bulgaria in 1982 and now a resident of Texas, Miroslav Penkov has been piling up accolades since he launched his fiction career a decade ago: The Southern Review’s Eudora Welty Prize, inclusion in Best American Short Stories, a PEN/O’Henry Prize, etc. His debut short story collection, East of the West, reviewed here at FWR, was published in 2011 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, and earlier this week they published his debut novel, Stork Mountain.

In this new book, a native Bulgarian slips out of grad school in America to visit his grandfather back in the old country, only to find himself embroiled in age-old conflicts and crossed wires beyond his control or understanding. The ability to enter into the private quandaries of the self, which earned him praise for East of the West, is again on full display here. The broader canvas of the novel offers Penkov many opportunities to find the nooks and crannies of our lives where we can make sense of our own conundrums—or, if we can’t make sense of them, at least sit down with them and understand how they have shaped our lives.

Miroslav Penkov teaches creative writing at the University of North Texas, where he edits The American Literary Review. I will now step out of the way and let him talk about his work.

Interview:

Steven Wingate: Can you talk a bit about the transition from the short story to the novel? I’m particularly interested in the way you inhabit your characters. In East of the West you lived inside the skin of many characters for a short while, whereas in Stork Mountain you’re going the distance with just a few. And were there any changes to your writing regimen or habits in this transition?

Miroslav Penkov: I grew up reading short stories, and I’d go as far as to make the big pronouncement that in Bulgarian literature the short story takes central stage over the novel. Maybe because of how strong our oral tradition was during the centuries of Ottoman rule when tales were passed not in writing but in song. Maybe for some other reason. But I fell in love with short stories at an early age and began writing them when I was twelve. Only, the stories I wrote kept getting longer and more intricate. Or, I should say, convoluted in the number of tales within tales they contained. Over the years, I’ve written five manuscripts long enough to be labeled novels; manuscripts, which of course, no one will or should see.

What I’m trying to say is that for me there was never a definitive moment of transition from story to novel; I didn’t tell myself on some faithful day, Okay, you’ve written a collection, now try your hand at a novel, because I’ve been trying to write both since the beginning.

As far as inhabiting characters, be it in stories or this novel, I try to do so fully, even with characters whom I may not approve of in real life. It’s not that I try to understand them—what they desire, fear, struggle for—it’s that I try to be them. Writing has allowed me to come very close to that which in psychedelic literature is described as “ego death”–the complete dissolution of the self.

As far as inhabiting characters, be it in stories or this novel, I try to do so fully, even with characters whom I may not approve of in real life. It’s not that I try to understand them—what they desire, fear, struggle for—it’s that I try to be them. Writing has allowed me to come very close to that which in psychedelic literature is described as “ego death”–the complete dissolution of the self.

The only change in regimen that came with writing Stork Mountain was that I had to write every day for longer stretches of time. I can usually finish a first draft of a short story in, say, ten days and then take a break before rewriting it (though those rewrites can take, on and off, months, or even years). But with a novel, I think it’s important not to lose momentum, not to allow characters and story to go stale. So it took some discipline to carve out the time for writing every day for a few weeks without interruption. For me that’s tough to do when teaching. But I think I was most disciplined while writing the novel in Bulgarian. I knew that I had to translate/rewrite 100,000 words and that the Bulgarian publisher had given me approximately eight months to do so. So I wrote every day for months, five, six hours a day, and that commitment really surprised me. I didn’t think I had it in me, the endurance to carry out such a labor-intensive project.

Each fictional work comes to its own terms with autobiography. Is there a difference in the deals you negotiated with autobiography for East of the West as opposed to ones you negotiated for Stork Mountain? If you feel a difference, how do you account for that?

There is so little autobiography in my stories that I get a bit irritated when readers start assuming it’s my own life they see on the page. With the collection, the first-person point of view doesn’t help, of course, nor do some basic factual similarities that I included in some stories, just for the fun of it. But I really, really don’t want to write about my own life. In fact, I try to go to great lengths to imagine and experience lives that are very different from mine.

In Stork Mountain there is even less autobiography. I can think of a single bit: like the narrator’s grandfather, my own great-grandfather had resigned from the Communist Party and as punishment the Party had sent him to teach in a mountain far away from home (the Rhodope Mountains, not Strandja). That’s it. The rest I made up. I see, for example, a lot more similarity to my own character in someone like Elif, the rebellious daughter of the village imam, than in the narrator, the weak, and often confused “American” who feels like he can and should fix the lives of those around him.

In reading Stork Mountain, with its encounter between grandson and grandfather, I couldn’t help think of another recent novel by a Bulgarian—Georgi Gospodinov’s The Physics of Sorrow—in which the grandson and grandfather are essentially melded into one character. What is it about the contemporary moment of Bulgaria and its diaspora that makes this encounter with the past so important? And why that generation at this time?

Of course one could argue that like for the rest of the world the twentieth century was terribly tumultuous for Bulgaria; that Communism plunged us into forty-five years of darkness, and that to free ourselves from this yoke, to heal these wounds, to find catharsis we must not rush to move on, but instead return once more into the dark, this time armed with the light of literature, of art. But such need for coping with the past could probably be discovered in all generations, in all moments in history, and that’s why I don’t think there is anything that special about this particular moment of Bulgaria, anything that special about our generation (though, strictly speaking, my generation is not that of Georgi Gospodinov’s). All generations are special. All generations are hurt and traumatized and all generations must seek connection to and ultimately liberation from those that came before them if they are to move forward on their own accord. That’s Faulkner for you; someone whose philosophy influenced me very much while I studied and lived in Arkansas (even if I found and still do find many of his novels difficult to read). It’s impossible to know yourself, to understand the present, without first trying to comprehend, as best as you can, the past in its many iterations; a past that isn’t even past and all that shebang.

In your acknowledgments you thank the Bulgarian musical group Isihia. I looked them up (and loved their music) and found this in their artistic statement: “Most threatening to the Bulgarian nation today are not the political failures, the economic instability, not even the demographic collapse, but the weakness and impersonality of spirit. In such times, each nation turns to the stronghold of its traditions and history where its hidden strength lies.” How do you respond to that statement, and does your work in Stork Mountain—which goes beyond mere grandfathers to encounter a wide swath of Bulgarian history—share anything with Isihia’s project?

Isihia have been important to me and these days I write almost exclusively listening to their compositions; like a mantra, their music elevates my mind and keeps it at a certain height. But I get a bit weary every time there is talk of preserving the strength of a nation by diving into the days long gone and rescuing from them some true, proper, forgotten values. To seek strength in the past alone–a past often conveniently molded by our vantage point in the present–can be a dangerous thing in the wrong hands.

The idea of some deep ancestral connection has always been very interesting to me. The idea that blood connects us and speaks to us and through us across the centuries and generations; that one is Bulgarian by virtue of the Bulgarian blood which flows in his veins. I explored this idea in many of my stories in East of the West, and when I sat down to write Stork Mountain I was prepared to continue along the same lines–grandfathers and grandsons connected by blood. But the more I wrote, the more I sensed some even deeper, even greater connection–not one soaked in blood, but one defined by our common humanity. I don’t want to spoil a big twist, a big revelation in the novel, but by the end of it, the narrator realizes (and I with him) that his blood, his grandfather’s blood, all that means nothing of substance; that it’s all empty rhetoric. And that they share a deeper, stronger bond entirely independent of their genes, of their culture and tradition.

The idea of some deep ancestral connection has always been very interesting to me. The idea that blood connects us and speaks to us and through us across the centuries and generations; that one is Bulgarian by virtue of the Bulgarian blood which flows in his veins. I explored this idea in many of my stories in East of the West, and when I sat down to write Stork Mountain I was prepared to continue along the same lines–grandfathers and grandsons connected by blood. But the more I wrote, the more I sensed some even deeper, even greater connection–not one soaked in blood, but one defined by our common humanity. I don’t want to spoil a big twist, a big revelation in the novel, but by the end of it, the narrator realizes (and I with him) that his blood, his grandfather’s blood, all that means nothing of substance; that it’s all empty rhetoric. And that they share a deeper, stronger bond entirely independent of their genes, of their culture and tradition.

Nikos Kazantzakis quotes this old Cretan proverb: “return where you have failed, leave where you have succeeded.” And I believe the wisdom of this proverb can be extended beyond the personal level; that not just individuals, but whole families, nations, the entire humanity can be guided by the idea of failing a task, time and again, until at the end a single person resolves it for the rest of us. And then, all of us, even the ancestors who have come to pass, will be liberated, free to move on, to leave through the success of their one victorious descendent.

Imagine, in other words, that Faulkner is quite literally right; that the past hasn’t passed yet and that it exists even now, simultaneously, with the present. Of course changing something in the present affects what comes after–that’s cause and effect, that’s karma. But what if changing something in the present could affect that which has already passed? Is it possible for us to solve a problem our ancestors struggled with and by doing so liberate not only ourselves but also them, retroactively, and allow them repose as well? Reversing the direction of time’s arrow was an idea I wanted to explore in this novel.

As much as history figures in the novel, Lethe—in classical Greek mythology the river of Hades that brings forgetfulness—also gets mentioned quite a bit. It feels related to the reversal of time you just talked about, or trying to achieve a balance between remembering history and resolving it. Can you talk a bit about Lethe and how it figures into Stork Mountain?

There is a moment early in the novel in which the grandfather speaks of what he calls each person’s two deaths–the first one, that of the body; the second, that which comes when a person fades from the memory of those who could remember him. “People don’t write history books,” the old man says, “so others can learn from their mistakes. They write them so they will be remembered. And I for one will not remember.”

I’m not sure I necessarily agree with this sentiment, though it’s impossible not to think of Shelley’s Ozymandias. “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!” And all that’s left is two trunkless legs of stone in the sand. But the grandfather believes it because for a long time it was through willful forgetfulness that he tried to cope with his past. In his youth, he was terribly hurt by the Communist Party so now in old age he wishes for the people who hurt him nothing but the Cup of Lethe. “May no one remember them in fifty years,” he says. “May their children forget them. I certainly have.”

Of course, he hasn’t as the later pages reveal, but the idea of oblivion as the ultimate punishment was interesting to me. In the novel even Perun, the great god of the Slavs, was terrified not of the Goddess Old Age, which he knew would eventually come for him, not of Death, but of Zabrava, Oblivion, the goddess that rules all gods.

I think, however, that by the end of the book, the finality of oblivion becomes much less terrifying to the old man; in fact, by the end of the book, he willingly surrenders himself and his past to the erasing flame of the ritual fire; flame which obliterates and by doing so liberates all.

One of my favorite passages in the novel talks about the conflict between body and spirit, and it comes as your protagonist begins to get deep into his grandfather’s convoluted history. “Don’t wound me,” the body shouts, but the spirit asks to be cut because “in ease and comfort the spirit withers.” Could you talk a bit about that passage and why it’s particularly important at that point in the novel?

Practically every character in this novel, a novel which concerns itself so much with the rituals of the Bulgarian/Greek fire dancers, at some point has to make a choice–to plunge into the fire and be purified, or to remain safely outside the flame yet still impure and unchanged. The problem with fire is that it burns. And what body really wants to be in pain? This clash was interesting to me–the spirit seeking the flame, and the body resisting it. It’s a fascinating struggle–one that is very human and that so many of our myths, stories, and religions have tried to deal with–the struggle which arises when the spirit manifests in a physical body.

Toward the end, Stork Mountain reminded me of Henry James’ The American in the way its American protagonist comes to Europe and becomes embroiled in battles beyond his understanding. Yet its protagonist, though referred to as amerikanche by the woman he falls in love with, isn’t particularly American yet—being a relatively recent arrival. He became especially representative for me of the Bulgarian diaspora in the west, the many thousands who left after 1989. If he’s not consciously autobiographical, what aspects of that diaspora does he embody for you? Or to put it another way, what questions might that diaspora be asking itself that are reflected in the novel?

Yes, I really don’t think the “American” in the novel is all that American; he can’t be, not if he’s lived through the winters that came after Communism fell in Bulgaria, the lines for bread, and the hours of power blackouts. But of course in the eyes of the people in the small village he visits, he is as American as George Washington. And yet inevitably, he is influenced and changed by American culture, by its language and values and expectations. He believes, for example, that Elif, the daughter of the oppressive local imam, is entitled to freedom; and so he meddles in her affairs, always with good intentions, and causes her and himself much hurt; but in the end, like fire, he helps her take that freedom, even if it is at a great personal cost for both of them.

There are certain colonialist traits in his character, I think–a Western “civilizer” arrives in a distant place and promptly resolves to change everything around him according to his own rules. But I can’t presume to argue that this boy, the novel’s narrator, is a representative of the Bulgarian diaspora in the west. One reason I don’t write about this diaspora is that I hardly know any of its representatives. By sheer circumstance, I live in a town in which I know no other Bulgarians. My wife is Japanese and at home we’ve created for ourselves a bizarre bubble that hangs between three cultures and belongs fully to neither one of them.

There are certain colonialist traits in his character, I think–a Western “civilizer” arrives in a distant place and promptly resolves to change everything around him according to his own rules. But I can’t presume to argue that this boy, the novel’s narrator, is a representative of the Bulgarian diaspora in the west. One reason I don’t write about this diaspora is that I hardly know any of its representatives. By sheer circumstance, I live in a town in which I know no other Bulgarians. My wife is Japanese and at home we’ve created for ourselves a bizarre bubble that hangs between three cultures and belongs fully to neither one of them.

In my mind the boy (and maybe that’s one reason he remains unnamed) is a character that transcends the label of “immigrant”–he’s an epic hero who goes through the seven parts of the novel the way an alchemical element passes through seven distinct stages of purification on its way to being transformed into the philosopher’s stone.

Finally, back to William Faulkner. His Yoknapatawpha county, where he set his fiction, was a place of ancient conflicts that seem doomed to repeat. It’s a place where people take turns screwing each other over, much like the Strandja mountains in your novel. Do you see yourself returning to that place in your fiction? Does it hold more stories for you?

The world is full of stories; and who knows, maybe the world is a story. I see no reason why I shouldn’t return to the Strandja in another book if the story required it. But I must make one thing clear: the Strandja Mountains in this novel are not the Strandja Mountains that spill between Bulgarian and Turkey. The mountains in this book are my own–I lay claim to them because they arise not just from what I saw when I visited their villages, but also from what I saw and lived through in my childhood, in a village in North Bulgaria, in another mountain altogether. It’s safe to say that the Strandja of Stork Mountain is about as fictional as Yoknapatawpha county or Macondo or Castle Rock.