Editor’s Note: As we approach our tenth year of publishing Fiction Writers Review, we’ve decided to curate a series of “From the Archives” posts that we’ll re-publish each week or so during 2017. Some of these features are editor favorites, some tie in with a new book out from an author whose worked we’ve covered in the past, and some are first conversations with debut authors who are now household names.

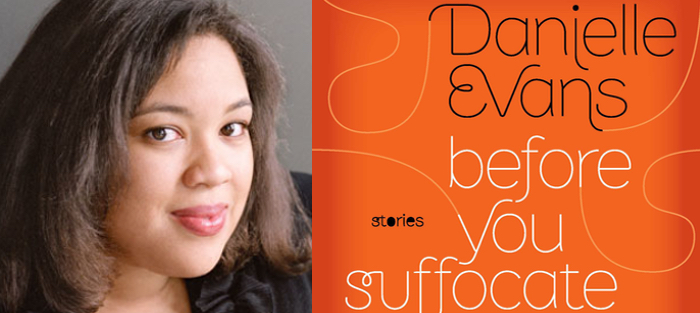

This week we’ve returned to Contributing Editor Melissa Scholes Young’s interview with Danielle Evans, which was originally published on March 23 of 2011. Evans is the author of the 2010 short story collection Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self. Her work has received the PEN American Robert W. Bingham Prize, the Paterson Prize, and the Hurston-Wright Award. She was also recognized by the National Book Foundation in 2011 as part of their “5 under 35” program. Scholes Young’s debut novel, Flood, will be published by Hachette in June.

I’ve always loved secrets, especially the juicy ones layered with details so convincing they feel like they never should have been whispered to me. The stories in Danielle Evans’s debut collection, Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self (Riverhead), are both revelatory and inviting, and the secrets that spill onto the page challenge the reader to confront complex issues. In “Snakes,” a biracial girl is sent to her white grandmother’s house for the summer and forced to cut her braids because her grandmother says she looks like “a little hoodlum.” In “Virgins,” two friends navigate the adult world of boys and men long before they seem ready. In “Jellyfish,” Evans writes about a middle-aged man examining his and his daughter’s life after his roof has collapsed on top of him. The stories are full of struggles told from the “outsider’s” point of view, and one after another they satisfied my voyeuristic curiosities and nosy lusts.

Before her reading at the 2010 Devil’s Kitchen Literary Festival in Carbondale, Illinois, Evans sat on a fiction panel and answered questions about her collection and the writing life. I had the pleasure of chatting with her afterwards and extracting even more secrets to her success.

Interview

Melissa Scholes-Young: In the article that appeared about you in the Washington Post, you called your characters “outsiders.” Why do you think so many of them are struggling to find a place they fit?

Danielle Evans: It’s funny, because I don’t actually think of most of the characters as, fundamentally, outsiders. I tried to wiggle out of that description a little bit. I think for most of the characters, the trouble comes not from a sense of outsideness, but a sense of trying to belong, or actively belonging, in more than one place at once. An actual outsider wouldn’t, for example, face the sorts of choices Erica does in “Virgins,” because a teenager who was actually an outsider wouldn’t be invited into those kinds of potentially dangerous or exciting situations, and wouldn’t have the sort of emotional entanglements that drive Erica to do what she does. Tara’s problem in “Snakes” is not so much that she’s an outsider, but that she’s inside this dysfunctional family that’s working through its own issues, often at her expense. It would be a completely different story if the racism or other trouble was actually coming from some structure that she was completely outside of, as opposed to from her own relatives. Angel’s sense of displacement and inadequacy in “Harvest” stems mostly from the fact that she’s already inside a particular kind of institution. She wouldn’t have the kind of outlook that she does if she were pregnant at home in her own neighborhood and not comparing herself to people from very different backgrounds and preparing herself for a different kind of life than the one that might have been expected of her. Eva in “Jellyfish” perhaps most neatly fits the mold of an outsider, but even she has all of these coexisting loyalties and senses of self.

Do you think the characters succeed in becoming “insiders,” meaning, do they find an identity with which they’re comfortable?

I don’t know that I would read those two descriptions in the same way. Part of finding a comfortable identity, for many of these characters, is becoming comfortable with the idea of constant transition, of code-switching in both language and behavior. In most of the stories the problem is not that the characters are trying to become insiders, but that they’ve been instructed to get someplace, and then they get there, and then, to quote Gertrude Stein, “there is no there there.”

I think the stories often end with a sense of the character discovering or admitting something about himself or herself, and even when that discovery comes about painfully, there’s some hope that the character will be able to take that knowledge and do something different in the future. Hope, of course, is not the same as promise, and some of the characters’ outcomes are more ambiguous than others. I don’t know that they all end up OK, but I hope there’s something interesting for the reader in worrying about those outcomes.

Many of your stories reveal the struggle of living between two cultures and/or between two races. Would you say post-racialism is a theme that unites most of these stories?

Well, I think in a truly post-racial society, the idea that there exist multiple and distinct cultural and racial spaces, and that they each bring with them their own expectations and burdens, would not exist or shape the characters’ lives. Most of my characters are somehow marked or shaped by their racial identities in the present or by an experience of the past that is deeply rooted in our country’s struggle with race and racial equality. I’m not persuaded that we live in a post-racial society. There continue to exist deep inequalities, and we are actually, as a society, resegregating along both class and racial lines. There is certainly an abundance of hate crimes and hateful language, and I think the perspective of the book reflects that.

Having said that, I am slightly more persuaded by a more Hegelian definition of post-racialism, which I first heard used in a lecture by Professor Paul Taylor at Temple University. It borrows from theories about “the end of art” and “the end of history” and posits that we are at the end of a particular linear progression of race as a concept, and in an era that necessitates a more pluralistic discussion, in which we must constantly identify what it is we’re talking about when we talk about race. Some of the characters in my book are contending with a world for which they have been unprepared by the past. The possibilities and choices that they have would have been impossible in many cases for their parents. The rules of the world that their parents prepared them for have changed in some fundamental ways and remained unchanged in others. Part of what’s confusing is determining which is which.

You write a lot of strong, saucy women. What women in your own life or in literature have most influenced your writing?

Well, I don’t think I know that many women who are not, in some way, strong. In some ways, I started writing more against the portrayal of women in literature than because of it—early on, I read a lot of stories in which the female characters seemed weak or stupid or, most criminally, uninteresting or lacking credible desires, and I wanted to make sure I was always writing women who made choices, who behaved, on occasion, emphatically, even if they were wrong. I have been lucky enough to encounter, as my reading world expanded, many authors—of both genders—who do justice to their female protagonists.

I like Jennifer Egan’s work because her female characters can be vulnerable without that vulnerability becoming trite and boring. I admire Toni Morrison’s work tremendously because she doesn’t even entertain the idea that a feminine concern is an unserious concern, and the interior lives of her female characters get a tremendously respectful and eloquent treatment, plus she does a beautiful job of exploring women’s relationships to each other. In her world, men are allowed to—not required to, but allowed to—be incidental to the bigger picture. That’s rare in literary fiction, rare to a somewhat astonishing degree when you think about how common the inverse is: stories in which women are incidental to men’s experience abound.

What’s your recommended reading list from these two authors, Jennifer Egan and Toni Morrison?

You really can’t go wrong with anything Morrison, but for first-time Morrison readers, I’d recommend starting with Jazz or The Bluest Eye. I loved Egan’s A Visit From The Goon Squad enough that I immediately sought out other work of hers, starting with Look at Me, which I also highly recommend.

Yesterday on the fiction panel you mentioned your reluctance to read “Virgins,” the story that debuted in the Paris Review. I’m curious about your hesitation. Is it the audience’s reaction or something else?

I think my reluctance to read “Virgins” has less to do with where I am, and more to do with the fact that for years it was the only thing I’d written that anyone had really heard of, so when I was asked to do a reading, I was always asked to read it, and I got kind of sick of it, and also worried that people would assume it was the only kind of story I could write, and also annoyed by how surprisingly often complete strangers would think it appropriate to speculate about or directly ask about the circumstances under which I lost my own virginity, because I read a completely fictional work called “Virgins.”

Someone did that?

It’s sometimes flattering that people assume your work is true, because you want the characters you create to be that convincing, but it’s also a bit grating. As a fiction writer, your job is to make things up, so when people insist that you haven’t made anything up, it can also feel like they’re assuming you’re bad at your job.

I do sometimes say that I can’t read “Wherever You Go, There You Are” on the east coast, because my father says that if my family ever hears it I will never be allowed to go back to Delaware for a family reunion. He’s kidding. I think.

These are fictional stories, of course, but how do you both pay homage to home and reveal the delicious dysfunctions every writer observes?

I think one of the pleasures of being a writer is that you can go back into those moments where life could have been more interesting, and make it so, without actually having to pay the price in lived experience. Most of my work starts with either “why” or “what if.” I hear about something, or imagine a scenario, and I have no idea why someone would behave that way, so I write my way into an explanation, or, I think about a situation in which some sort of tension or disaster was avoided or defused, and wonder how it might have gone differently. Sometimes that means changing the outcome. Other times it means changing the entire dynamic of the situation so that it happens to a different person or so that something invented in the character’s past makes them a different enough person to make a different kind of choice.

I think one of the pleasures of being a writer is that you can go back into those moments where life could have been more interesting, and make it so, without actually having to pay the price in lived experience. Most of my work starts with either “why” or “what if.” I hear about something, or imagine a scenario, and I have no idea why someone would behave that way, so I write my way into an explanation, or, I think about a situation in which some sort of tension or disaster was avoided or defused, and wonder how it might have gone differently. Sometimes that means changing the outcome. Other times it means changing the entire dynamic of the situation so that it happens to a different person or so that something invented in the character’s past makes them a different enough person to make a different kind of choice.

How do you navigate that line between fact and fiction? If you’re writing a fictional character’s direct experience, does any of you as the author overlap on the page? Or is all of life just good material?

I don’t think fact ever really comes into it. Once upon a time I wanted to be an anthropologist when I grew up, and part of what deterred me from pursuing that was that I realized I have no loyalty to facts. I have a certain degree of loyalty to truth, but it would frustrate me that I was locked into working with things that more or less actually happened or things people actually said. Part of the fun in being a fiction writer is never having to feel guilty about departing from what actually happened, and also knowing that if you’re doing your job, you’ve gotten far enough away from a recognizable version of events that you haven’t just stolen the details of someone else’s life or republished your own diary, but instead you’ve used a particular experience or question or sentence or feeling as a jumping off point and ended up somewhere else entirely.

I’d love to hear a little about the process of writing this collection. As an MFA student, most of us are putting together short story collections. What advice do you have for the student of Creative Writing?

I think the best advice, trite though it may be, is to do your work before you worry about anything else. Go where the writing takes you. I cost myself almost two years of writing time once by trying to force my novel to be something it didn’t want to be. I think it’s easy to get distracted by the idea of outcome—and I realize these issues aren’t always distractions, because it’s important to feed yourself and pay your rent—but at the same time it’s generally impossible to tailor your writing for a particular market or magazine or job and not lose something in the process.

At Southern Illinois University I’ve taken workshops from both Beth Lordan and Pinckney Benedict, both of whom have written short story collections, and we’ve talked a lot about the form of the short story. When you teach the short story, what formal elements do you focus on? How do you want your students to approach the short story?

I think a lot about Vonnegut’s edict that a short story should start as close to the end as possible. Of course, in order to do that, you have to unravel the actual end of the story, and you have to define that “as possible.” I also think a lot about voice, which is a concern that goes beyond the first person, and about perspective. I’m interested in how writers fuse physical territory and emotional territory. In a good story, the physical descriptions sing, and feel completely organic to the narrative voice; in a clumsy story they feel pasted in, often because they literally are pasted in. Mostly though, I want my students to approach the short story—as readers and writers—with joy. My favorite part of my job is not when a student brilliantly analyzes a story but when a student is stunned and grateful to have read an assigned story because it changes their concept of what literature can be.

And what would you say is the value of a short story in our modern world? Is it a dying art? Or is there something unique that a short story can accomplish that a longer work can’t?

And what would you say is the value of a short story in our modern world? Is it a dying art? Or is there something unique that a short story can accomplish that a longer work can’t?

I would say the value of a short story is the same as the value of all literature—that it allows a person to confront the world in a new way, that at its best it has the power to act as a transformative experience, and to leave the reader changed—smarter and more empathetic. I think there’s something especially lovely about being able to have a complete, meaningful emotional experience in the time it takes to read ten to twenty pages. At the same time, I am a bit wary of defending or promoting the short story as a concept, rather than defending and promoting individual short stories that I love. There’s been a certain pushback to “save the short story” of late, and insofar as those kinds of projects introduce people to great writers, or resist the publishing edict that short stories don’t sell, which has always seemed somewhat defeatist and self-perpetuating to me, I’m all for it. But there’s something strange to me about the language. Good short stories are arguments for their own existence.

I’ve learned from Jacinda Townsend, another professor of mine at SIU, that the process of writing a novel is a very different animal than a story. You’re working on a novel next, right? How does the process differ from drafting the stories in Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self?

Well, by necessity, it’s a more singularly focused process. You can’t abandon a novel for as long, because it won’t be there in the same way when you get back. You can’t write a novel in a single sitting, counting on your ability to go back and fix all the problems, or toss it out altogether if it doesn’t take. You can jump around a bit once you have an outline, but I find it harder to punish the novel when it’s being unruly by abandoning it to work on an entirely distinct piece, the way I might with an unruly short story. But, it’s also new pleasure—I am loving being able to play around with different kinds of textual interventions and voices in the same book. I like finding unexpected thematic or structural connections that then become deliberate. There are people who have posited that because I tend to try to sneak three or four plots into a short story, I am secretly a novelist, but the actual secret is I just really like interconnection and plots that intersect or circle back to each other. I am trying to sneak about ten plots into the novel.

I won’t tell, Danielle. Your secrets are safe with me.