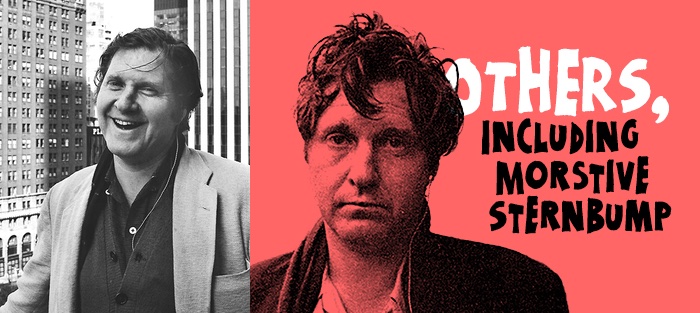

The writers I spend the most time talking about writing with are usually the ones who approach writing as a sort of “coddiwomple,” a journey with an unknown destination. As a fiction writer, I don’t see my work as the answer to a question but rather as a way to discover a question. I am always looking for writing that seems to challenge, counter, or rise above its own limitations. Lately, I have been eager to read writing that speaks intimately to me and expresses itself as a playful journey with words as the keys to unlocked doors. I picked up a copy of Marvin Cohen’s How to Outthink a Wall: An Anthology (Verbivoracious Press, 2016) and the 40th anniversary edition of the novel Others, Including Morstive Sternbump, originally published by Bobbs-Merrill and rereleased by Tough Poets Press in 2016. Known for making his “prose as poetic as possible,” I found his sentences to be a reminder of the pleasure of rubbing syllables together.

I had found what I was looking for in Marvin Cohen’s work. I fell into a whirlwind and followed his humorous and playful language to the end. Wanting more, I got my hands on a galley of The Self-Devoted Friend, rereleased from Tough Poets Press, June 2017.

Born in Brooklyn in 1931, Marvin Cohen has often described himself as one who has “risen from lower-class background to lower-class foreground.” His first published piece, “Prose Poem,” appeared in the 1960 anthology The Beat Scene (Corinth Books) alongside works by Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti. In the ’60s and early ’70s, Cohen was everywhere. His work has appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Village Voice, The Nation, Harper’s Bazaar, Vogue, Fiction, and The Hudson Review. The New York Times Book Review dubbed Cohen “a striking, fresh talent” who “stands outside current literary preoccupations” and praised his 1967 debut, The Self-Devoted Friend, as “a tour de force of serio-comedy, a sort of superb clowning in which pathos and absurdity intertwine as they do in a Charlie Chaplin film.”

Timing and chance met up, and Rick Schober of Tough Poets Press, a one-person independent publisher of “rediscovered” literary fiction and non-fiction generously set up a telephone conversation between Marvin and myself. It was one of the most memorable phone conversations I have ever had. Marvin’s wisdom, quick wit, sincerity, humor, and words of advice offered me a treasure that I imagine most writers dream of receiving.

Interview:

Nina Buckless: How does it feel to have your work back in print after so many years?

Marvin Cohen: It feels like a different person wrote the work. It was done half a century ago—maybe more than half a century ago. When I think back on it, it feels as though two men are wearing the same costume in order to make a bear perform on stage. They both get into the same bear suit together, as though one person were to play the role of the front legs of the bear and a separate person were to take on the role of the back legs of the bear. Two different people in one body. I feel isolated in a way, because a half-century has gone by. Some people don’t even have the good luck to last one of those half centuries. In a way, I am a stranger to what I did so many years ago. In a kind of a superstition, I am loath to reread what I once wrote so many years ago.

Superstition? Can you elaborate? That is an intriguing thought.

Some sort of an irrational fear. Or, simply not wanting to touch upon what was in my head and charged the writing back then. Once the act of writing is complete, for me it is done. So, I just write new things.

Let’s talk about The Self-Devoted Friend.

Let’s talk about The Self-Devoted Friend.

The Self-Devoted Friend is really the same person. I see one person as having a voice who thinks about what to do. Then there is a counter-voice who thinks, “Hey, wait a minute, maybe that is not such a good idea.” They may have a clash or a controversy. What approach to make about decision-making? What about if I am in a certain mood and a contrary mood is going to break into the first mood and dispel it? Then, there could be a conflict. It’s like if there is a Parliament in Britain and there is a party that is more in power and then the back bench is the loyal opposition to the party in power—so then they can have debates. In a less formal way, everybody is saying, “Well, I’ll go ahead on this,” and the other party is saying, “No. No. You better not do this, you’ll be sorry.”

It’s like we all have our true “self” but then we have a “self-devoted friend” who acts as an intercessor? Or the contrarian? Intuitive voice or conscience?

I think that all of us are bi-focal. That the brain is bi-focal in the way some leaves are bi-focal. And any idea that enters my head may cause a reaction from another part of me. Let’s say you’re invited to a party where you have had some bad relations with the host. You are attracted to the idea of going to the party but, on the other hand, your memory tells you, “Better stay away, because the conflict that you had last time was painful, and you don’t want to repeat that.”

There is something both beautiful and humorous about that which shines through in much of your poetry and prose. Why do you think such potentially uncomfortable situations, thoughts, moments can be funny?

A lot of things are inherently funny when there is a conflict and an opposition. We’re not simple people. Everybody is complex. A lot of times we just do spontaneous habitual acts. But, the times that we have conflict within ourselves, that’s the idea of The Self-Devoted Friend.

You grew up in a time before the internet and television. Today many people rely heavily on computers for their social interactions or even for dating. What was that like for you?

I grew up just before television and way before computers. Before recording mechanisms. Or, most recording mechanisms were pretty blunt back then. But now, the whole world of acoustics is available to us. We have access to theater events, movies, entertainment. I have a channel on my television called Turner Classic Movies.

Oh, I love that! I enjoy viewing a good classic film.

And, I can hear it when I’m an insomniac. In the night, when I can’t sleep, I have the consolation of hearing that station and getting a movie. It is a comfort right at the fingertips. Another thing, I grew up hard of hearing. I only have one good ear.

Wow, I did not know that. I am deaf in my right ear, actually.

Well, my right ear is completely deaf, too. I often stand close to people in order to hear them. I grew up a bit isolated and lonely because it is hard to hear the drumbeat that normal hearing people can easily hear. That drumbeat of society. And, hard-of-hearing people have to make do and make special provisions.

The drumbeat of society! Can you expand on that idea?

The drumbeat of society! Can you expand on that idea?

There is a rhythm to society or places. People with normal hearing can easily eavesdrop. If they are in situations where there is a bus, a train, or a party, and they are not actively engaged with talking to somebody, they can still hear the room or the drumbeat. It’s very hard for normal-hearing people to have an empathy into a hard-of-hearing person’s challenges. In the same manner if someone has partial blindness, it’s challenging to have empathy into how a partially blind person views the world. Because we all assume normality. So, handicapped people then have to be socially clever and tactful to compile their friends and acquaintances to give them a break. In addition to going through lifelong stages of semi-poverty, I also went through challenges with hearing impairment. My hearing impairment began at the age of three and I only have partial hearing in my good ear. It comes with difficulty and embarrassment and I have to kind of persuade people in a friendly way to go out their way for me.

That’s fascinating to me. Because, I noticed a certain sound in some of your prose poetry, particularly in How to Outthink a Wall, which I found compelling. Some of the language of your prose poetry almost sounds like code-switching. There are contradictions and it has its own sound, or drumbeat I should say, that sort of mirrors a jazz composition. It all comes together, though, sewn delicately. The sound is offbeat and humming to its own generous percussion or drumbeat.

When I use words, one word leads to another and then my mind kind of works along puns and double entendre, whereby there is ambiguity in a phrase. In poetry, a lot of phrases could be interpreted in a few different ways. You need further embellishment for the next word or the next phrases. I don’t think along journalistic lines when I write. When I write, I write and put in jazz.

That reminds me of what you talked about when you spoke of the drumbeat of society.

I miss out somewhat because of my hearing handicap. I try to compensate by having special empathy where I really try hard to make up for missing things in the drumbeat of society. I’d like to leave myself open to what other people are saying and really try hard to understand others.

Is that partly why you leave much of your work like an open door? Leaving the reader with a golden key?

Yes, but I want the golden key to be enlightening rather than impossibly difficult. I don’t want to be difficult to the point of obscurity. I want to give my friend a break when I speak with him. Make illumination rather than ambiguity.

Speaking of illumination, let’s talk about solitude and how that works its way into your work as a writer.

Solitude is the breeding ground for creativity. Really, we think alone. When we write, we write alone. That’s when we come up with special ideas because we are communing with our own inner selves. When we are alone we can have post mortem in our own head. We can revisit situations and go over them in our solitude.

And what about the difference between writing prose poetry before the technological revolution and after or during it? Do you find in any ways that the contemporary environment around us today, the fast pace of technology, the internet, has altered or affected writing today?

I really love email writing. I love to receive it and to write in it. One reason that I don’t capitalize our sentences in the way that normal writing is because my brain goes quick and I want to keep up with the prose, the flow of words. It would impede me if I pay too much attention to capitalizing.

In that light, there is a playfulness in your writing that is very appealing. A feeling of freedom.

I’ve always been humorous. I’ve always had a funny bone. Entertaining people. Some aesthetic philosophers say that “creativity is play.” You are at liberty to make any sequence of words any way you want. And you take the responsibilities of how people are going to react. But in being playful, successfully playful, other people may be grateful that you have given them an occasion of humor.

I lived in very cheap apartments. In the Lower East Side in the East Village, there was a lot of drug trafficking but there were cheap apartments. I had part-time jobs. Like post office temporary during seasons when they needed more work, market research jobs, taking assessments of people’s opinions, being a messenger boy, serving ice cream from ice cream fountains. All different kinds of jobs that are not necessarily dignified. I had to take orders from people who were oftentimes younger than me. My circumstances are better now and I am happy to live in this comfortable apartment, which is in great shape, with my wife.

Going back to when we were talking about “space” and “environments” and how they affect us as writers, it sort of reminded me of H.G. Wells’s The Time Machine, from the classic film of the same title directed by George Pal and released in 1960. Because the main character, George, travels through time and place without ever leaving his living room having been confined to his time machine. So, the landscape and environment drastically change around him through time, yet he remains in the same space.

I see space as a metaphor for time. Because, it’s hard to conceive of time directly. Like it’s hard to look at the sun directly. It would harm your eyes. To use space as a metaphor, for instance the phrase, “It’s a long time since I saw you”—well the word “long” is a space metaphor. And what is being implied is “we really must shorten our absences” or “we must see each other more frequently.” That sort of puts it in a space concept. It is sort of periodical and sequential. A sequence. Wherever I am, my thinking is influenced by that place. And if you are in your own den, or personal room, where another person cannot come in. A Room of One’s Own was a Virginia Woolf title, where then the writer feels that their solitude is given the right place. Also, sometimes, if I am distracted by people, I could still carry my train of thought. For example, Jean Paul Sartre, in Paris, in the 1920s—he would be in an outdoor cafe and converse with the regulars there. That was one dimension of his activity. And in another dimension, he would have a notebook and he would write down his own thoughts so he could then multitask. Writers can multitask. A writer can serve the meal and still carry on his thought and then write it down as soon as the plates that bear food are plunked on the table.

I see space as a metaphor for time. Because, it’s hard to conceive of time directly. Like it’s hard to look at the sun directly. It would harm your eyes. To use space as a metaphor, for instance the phrase, “It’s a long time since I saw you”—well the word “long” is a space metaphor. And what is being implied is “we really must shorten our absences” or “we must see each other more frequently.” That sort of puts it in a space concept. It is sort of periodical and sequential. A sequence. Wherever I am, my thinking is influenced by that place. And if you are in your own den, or personal room, where another person cannot come in. A Room of One’s Own was a Virginia Woolf title, where then the writer feels that their solitude is given the right place. Also, sometimes, if I am distracted by people, I could still carry my train of thought. For example, Jean Paul Sartre, in Paris, in the 1920s—he would be in an outdoor cafe and converse with the regulars there. That was one dimension of his activity. And in another dimension, he would have a notebook and he would write down his own thoughts so he could then multitask. Writers can multitask. A writer can serve the meal and still carry on his thought and then write it down as soon as the plates that bear food are plunked on the table.

I’m going to ask sort of a random question if that is all right, in the spirit of thinking by association. How can writing work as petals of the flower of life?

When I start out on a piece of writing, I may have a vague concept that amuses me and is pregnant with possibilities. I’d like to give it body. To attempt a train of words. Where one word, or one sentence, or the beginning phrase can set the stage for what may follow. I have to make the second sentence come in harmony with the first sentence, but they have a counterpoint. The second sentence may have its own track, but they are still part of the same flower. Then, the flower goes on growing. So, the sequence of words goes on and is playful. I see the sequence of writing as playful, where one sentence follows and compliments another sentence, and then you can’t stop there because now you are in a groove. Then a third sentence comes on and you are having fun and now you are in business. Now a fourth sentence comes and now you have momentum because you’ve built up a sequence. It’s like how nature builds up DNA. The DNA strands grow. A flower grows from its DNA and, as writers, our minds open up to a flow of growth that keeps the sentences in fluidity with one another. Only later you can go over what you wrote and iron out inconsistencies. Often, revision sets a new network of growth going. So, sometimes our revisions inspire us to make a departure from the initial blossoming or budding of a flower. Adding an element of humor can lighten the flower and achieve its wonderful odor, and its wonderful shape and its wonderful color.

That reminds me of the playfulness between language and memory. Michel de Montaigne, in his essay “On Liars,” speaks of memory as a playful goddess.

Yes, it is because a goddess endows us with something wonderful that we cannot get anywhere else. It’s like a muse. A muse is a gift from heaven. Memory takes on different shades. Some of our memories are banal, some of our memories are much like a self-devoted friend. Sometimes it guides us, sometimes it can misguide us—because things change. Sometimes memory can be subject to a change of attitude of people. For instance, if you have a friend who was once very nice to you and then all of a sudden seems indifferent upon the next encounter with him or her, your memory serves you in a different way. Journalism is who what when and where—that’s journalism and it has its own function. But beyond journalism is creativity when you take certain elements in your memory and try to fabricate a new being.

Where do you draw the line between poetry and prose?

Well, I try to make my prose as poetic as possible. For one thing, I don’t want to say anything trite, cliché or banal. I want to put a new slant on things. I want people to take another look at the familiar in a way that makes the familiar seem unfamiliar. One of things that Montaigne did in his essays was that he said things that everybody really knows but hadn’t appreciated and recognized. So, he tries to make what is already familiar—to convert what is already known—into a revelation.

Any words of wisdom for young writers today?

My advice is don’t get addicted to computers and computer technology. Don’t get addicted to looking up things on your smartphone, or online. Or apps. Have more emptiness whereby some kind of fertile ground can grow out of your emptiness. If you have some unusual slant on things, write about it, because people like to see things in new and individual or unique ways. If you have some sort of new twist on how to interpret some aspects of reality, to interpret human relations, to interpret what goes in in people’s selfishness and people’s kindness. What goes on in relations between friends and loved ones? What goes on when there’s envy and jealousy? Competition? A lot of writers resent when other writers get published because they feel it is an arena of competition, so try to see things in a new light and write about it. If you are bogged down or stuck, put it in other terms and get the train of associations started again.

Well, you certainly have a train of associations running through all of your work.

Well, I want to keep myself on the rails otherwise I go off the rails. See? The train of associations can take different permutations and grow into odd directions. So, maybe follow it into those odd directions and you may come up with a unique growth.

New pieces of prose or poetry that you have been working lately?

I did some new things for the anthology How to Outthink a Wall. I have a chapter on recent work. Concerning my newest work, it is difficult to publish on the internet because of the nature of the format. My most recent work, manuscripts that are in hard copy format, are a challenge to transcribe from paper to the computer. So, anybody who is interested in working with me on how to get paper manuscripts typed into a format accessible for the internet would be great. I enjoy my apartment here with my wife in Manhattan. I live near the East river, instead of the Hudson river, and the apartment is in good shape. I care for my wife and help her out a lot. The apartment has many amenities and I am active. I walk for thirty minutes a day and I play ball. I have energy and time to work on my new projects. One of my miseries is that I have a lot of unpublished work and some of that work is probably better than my earlier work. Not having an outlet is my source of sadness. I have a lot of pieces of dialogue, short stories, and humor pieces that have never seen the light of print.