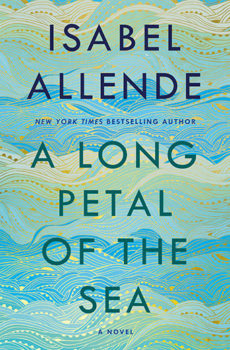

Isabel Allende’s newest novel, A Long Petal of the Sea (Random House), is a tale of love and exile, separation and reunification. It charts the history of “undesirables” fleeing the Spanish Civil War, following the story of Victor and Roser, along with over 2,000 other refugees, who embark upon a journey to Chile aboard the SS Winnipeg—a humanitarian act that the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda once wrote was a poem that could never be erased. This is a novel of love, poetry, sorrow, and hope, one that gives the reader a glimpse of the sacrifices that people make in order to survive, and the risks that people take to rebuild their lives in a foreign land.

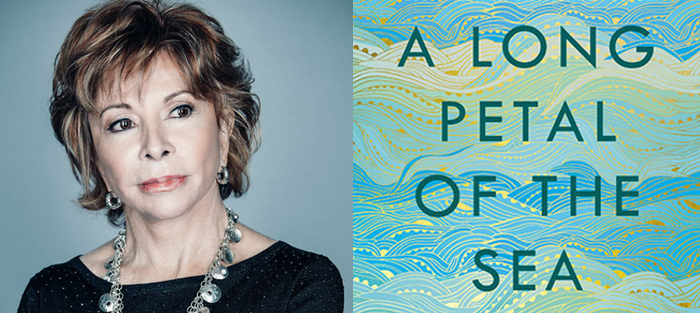

I have long been an admirer of the work of Isabel Allende. When I was in my teens, I wandered into a bookstore in California and heard her reading. Allende’s elegant presence and heartrending prose stirred something deep inside of me. My own grandmother was born in Barcelona in 1932 and was a child refugee separated from her mother and her sisters. Hers was a story I never got to know, because she died before I was born, and the loss of that connection has felt like a missing link throughout my life. Yet Allende’s voice has always helped me feel less alone. All those years ago, when I thanked Allende for the way she’d touched my own heart, she responded with grace, sincerity, and encouragement. Allende is one of those women whose elegance and strength is charismatic, and never to be forgotten.

Today, she still radiates the same beauty and compassion as when I first met her, even taking the time to ask me how I was doing when I recalled this story of our first meeting. She’s an individual who I admire as much for who she is as a person as on the page. And when I asked her how she managed to maintain her beauty and elegance, her determination and radiance, she responded by telling me it is simple: discipline. She wakes up in the morning and puts on her best, looks at herself in the mirror, and keeps going. She is a woman who lifts herself up and encourages other women to lift one another up, as well. And I am grateful to those other women who took the time to connect us for this conversation.

In addition to A Long Petal of the Sea, Isabel Allende is the author of twenty-four books, which have been translated into forty-two languages. She is the recipient of numerous international awards and accolades, and her work has been adapted for the film, stage, radio, and more. She is the founder of The Isabel Allende Foundation, which seeks to “empower women and girls worldwide.” In March of 2021, Ballantine will publish her new memoir, The Soul of a Woman, which asks the question: “What feeds the soul of a feminist?”

Interview:

Nina Buckless: A Long Petal of the Sea is a beautiful book. In the beginning of the novel, the main character, Victor, a young cardiologist—not even finished with his medical schooling—literally touches a human heart.

Isabel Allende: The heart appears several times in the book. The idea of resurrecting a dead heart—of the heart that comes back to life. It’s also my intention to touch the reader’s heart, so that’s why the book begins like that.

Later in life, Victor finds himself in a concentration camp after a political coup in Chile. He, along with many other people, are held captive and subject to cruel atrocities and oppression. Yet when the Commandant falls ill, Victor saves his life. He is a doctor, after all. At another point in the narrative, he tells his students: “…[t]he heart is a muscular organ that contains no mysteries. Those attributed to it are entirely subjective.” Then, in his later years, toward the close of the book, he says, “You know what I am most grateful for? Love. That has marked me more than anything.”

Later in life, Victor finds himself in a concentration camp after a political coup in Chile. He, along with many other people, are held captive and subject to cruel atrocities and oppression. Yet when the Commandant falls ill, Victor saves his life. He is a doctor, after all. At another point in the narrative, he tells his students: “…[t]he heart is a muscular organ that contains no mysteries. Those attributed to it are entirely subjective.” Then, in his later years, toward the close of the book, he says, “You know what I am most grateful for? Love. That has marked me more than anything.”

I think that basically he’s a very good person. He’s traumatized. For a person who has his temperament and personality, the idea of provoking suffering in another person does not even cross his mind. His job in the world is to heal. And so when he sees all this violence and cruelty and death, it’s hard for him to understand how people can do that. The model for Victor is a friend of mine called Victor Pey [Casado], who is very much like the character in the book. And in many of the conversations we had, in his later years, when he would look back at his life, he would always talk about the trauma, about how horrible people are, if you give them an opportunity—and the cruelty, the meanness, of the world. And then, together, we reflected upon what is the saving grace? What keeps us going? It’s love. He admitted that love had saved him. Often. It’s a theme in my life, really.

In your memoir Paula, you’re telling your daughter, while she’s in a coma in the hospital, about your family who is displaced and far away. “That’s what happens to exiles; they are scattered to the four winds and then find it extremely difficult to get back together again.” How does your recent novel reflect your family’s experience with exile?

Maybe I chose to write about refugees in my last three books, The Japanese Lover, In the Midst of Winter, and A Long Petal of The Sea, because I am a displaced person. There are more than 70 million refugees in the world today, most of them women and children.

Pablo Neruda made it possible for more than 2,000 people to make a new life, brought from Spain to Chile on the ship called the Winnipeg. And he once commented that the critics could erase all of his poetry (I’m paraphrasing here) but that his helping of those refugees was “a poem” itself, not just an action, and that that poem could never be erased. It will live on forever.

He wrote that in his memoir I Confess That I Lived.

In his poem “Return,” Neruda writes: “Foreigners, here it is, this is my homeland, here I was born and here live my dreams.”

Neruda has another poem in which he says he is an “eternal foreigner” because he traveled a lot—he lived abroad—and always wrote about Chile. His heart, his memory, was rooted in Chile. And in a way, that happens to me too. I have lived most of my life abroad; however, I can write about Chile without thinking. It’s in my blood. The roots of my memory are in my childhood in Chile. When Neruda presents his country and he says that this is my dream, it’s because, in a way, the country that you remember is an imaginary country. When you go back, it isn’t the country you were dreaming of.

I was astonished when Victor and his wife, Roser, go back to Spain. She turns to Victor and says, “Let’s go back to Chile, that’s where we’re from.”

They spend some time there, and they don’t find themselves at home. They can’t recognize anything. They feel that the country they left, that they remembered, is gone. There’s nothing left. I think that happens a lot to people who are displaced. The average time the average refugee spends away from home is between seventeen and twenty-five years. And that is in case they return. Because many never go back. By the time they do, they go alone—their children have grown up in another place and will not go to the old country—and when they go back they don’t have any friends, they’re older, they don’t have a job. They left something that is not there anymore.

They refer to this time in Spain as “dis-exile.” Did you invent this term?

I did not invent the word. I first heard that word in something that Mario Benedetti, a Uruguayan writer, wrote about. It means that going back (to the home you left) can be as hard as exile. The term is not in the dictionary.

We should have it in the dictionary today. Now. Because it’s very real.

It’s real.

At one point in the narration, you write: “Feelings fade; and forgetfulness slips into lives like mist.” Could you talk a little about that line and how literature works as a way to revive those feelings that fade, or to help us prevent forgetfulness?

He is talking about old age, no? And I think that literature has a very important role, because who writes history? The winners. Winners write history. Usually they’re white, male. The story of the women, of the people who’ve been defeated, the poor, the children, the displaced, that’s not there, ever, because they have no voice. And literature can give voice to stories that have been silenced. When we connect to the personal story we understand the macro-story. The history. The bigger story. Without even thinking about it, when I wrote The House of Spirits I told the story of a family, and I was also telling the story of a country. I wasn’t even aware that both stories were linked. What was happening to the family in the micro-world was happening to the country in the macro-world. Then, when I finished the book, I realized that’s what happens with history. Our personal stories are determined by the circumstances in which we live. If you have lived through the Holocaust, that has determined your life or your death. And that determines your story. So you cannot forget the big world, the big picture, the big circumstances. And that’s what I like to write about, the more epic story. For me it would be really hard to write a book that is very intimate. Let’s say a couple has a conflict that is very personal, closed. Intimate is the word. If it is not related to what’s happening outside, for me it’s like a bubble floating in nothing. I can’t tell that story.

He is talking about old age, no? And I think that literature has a very important role, because who writes history? The winners. Winners write history. Usually they’re white, male. The story of the women, of the people who’ve been defeated, the poor, the children, the displaced, that’s not there, ever, because they have no voice. And literature can give voice to stories that have been silenced. When we connect to the personal story we understand the macro-story. The history. The bigger story. Without even thinking about it, when I wrote The House of Spirits I told the story of a family, and I was also telling the story of a country. I wasn’t even aware that both stories were linked. What was happening to the family in the micro-world was happening to the country in the macro-world. Then, when I finished the book, I realized that’s what happens with history. Our personal stories are determined by the circumstances in which we live. If you have lived through the Holocaust, that has determined your life or your death. And that determines your story. So you cannot forget the big world, the big picture, the big circumstances. And that’s what I like to write about, the more epic story. For me it would be really hard to write a book that is very intimate. Let’s say a couple has a conflict that is very personal, closed. Intimate is the word. If it is not related to what’s happening outside, for me it’s like a bubble floating in nothing. I can’t tell that story.

Today refugees are some of the most vulnerable people in the world. What are your thoughts about refugees living through this Coronavirus pandemic?

Well, it’s horrible. Because every country is taking care, as much as they can, of their own citizens. And no one is taking care of the refugees. I have a foundation that works with refugees. It’s something that is very close to my heart, not only because I see the suffering, but because in one way or another, I have experienced it, so I can relate to it very closely. My foundation, The Isabel Allende Foundation, works with organizations on the border of the United States, on the Mexican side of the wall, where there are refugee camps. They don’t call them that, but if you take a look at it, thousands of people live in the worst possible conditions, in tents, or in makeshift tents made with pieces of plastic. There are not enough bathrooms. There is no running water. There is no safety. If a woman goes to the bathroom, she can be raped or killed or kidnapped on the way. And also, they live close together. Many people in the same tent. How are you going to protect them from the virus? Nobody cares. Nobody cares.

But you are doing some work with your foundation and you care.

Yeah, but what I can do—what N.G.O.’s can do—is minimal compared to what the government can do. And the government is creating the situation and making it worse. They are still deporting people—hundreds of people deported in a plane to some place that will receive them maybe.

We see this repeated in history. The message back in the ‘30s is similar to what governments are saying today, and the rhetoric…

…exactly the same rhetoric.

And your novel shows how a country embraced refugees. When Victor and Roser arrive in Chile, she is a pianist, starts doing orchestras in Venezuela; he’s a doctor, he saves lives, and becomes a professor.

Well, immigrants have made the United States. If given a chance, when they are welcomed into the society, they contribute much more than they take. And that is the case even with undocumented immigrants in the United States. But it’s very easy for the government—or whoever—to stir hatred and mistrust and blame others, like the Germans blamed the Jews. In the United States, they are blaming the Latinos now. But before it was the Chinese, and before that it was the Irish. So there is always someone to blame, someone to look down on, someone to abuse.

A scapegoat.

In Chile, what happened—and this is the beautiful lesson of the story (which is a real story, I didn’t make it up)—is that people received the refugees with open arms. They were at the port. My family was at the port—my grandfather!—receiving these people with open arms, offering them friendship, food, jobs, homes to stay in the meantime while they found a life. And the descendants of the Winnipeg passengers have transformed Chile. These are the scientists, the artists, the musicians, the astronomers—you name it. You will find the Catalan surnames of many of the passengers of the Winnipeg. They were given a chance and immediately embraced, and that changed everything.

It was Pablo Neruda’s idea to say let’s embrace these thinkers, creators, doctors…

It was Pablo Neruda’s idea to say let’s embrace these thinkers, creators, doctors…

Do you know that there is a document in which the Chilean government at that time instructed Neruda to select skilled workers who would teach their crafts to Chilean workers? The document said, “Don’t bring people with ideas.”[Laughter] I mean, some of these were refugees because they had ideas. That’s why they ran away.

One last thing. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin wrote: “We are not human beings having a spiritual experience. We are spiritual beings having a human experience.”

Oh, that’s beautiful. Yes. That is beautiful. I totally subscribe to that.