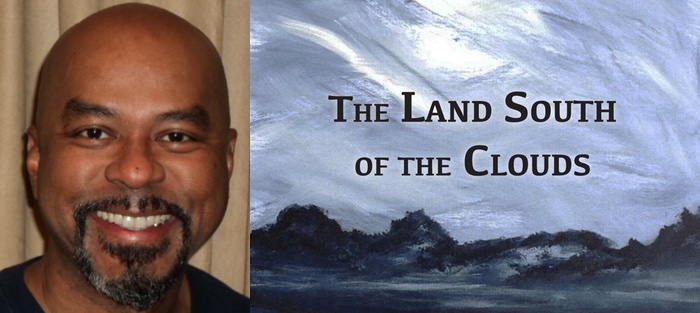

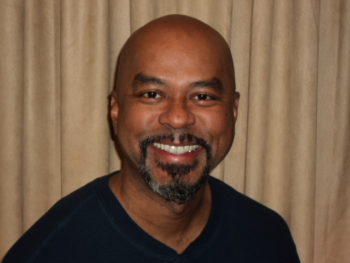

Genaro Kỳ Lý Smith, much like his work, defies easy categorization. Born in Nha Trang, Vietnam, Genaro was a child of diverse cultures, and he grew into a man of paradoxical gifts. He is warm and pathologically pleasant, quick to beam his contagious smile or release his booming laugh. Yet simultaneously, the insights in his work feel hard-fought and earned, dragged up from a place in the psyche far from laughter and merriment.

His first book, The Land Baron’s Sun: The Story of Lý Loc and His Seven Wives (UL Press, 2014) is both a moving singular narrative and a collection of lyrical poems. The narrator of Smith’s The Land South of the Clouds (UL Press, 2016) is ten-year-old Long Vanh, a biracial child attempting to make sense of the chaos world of 1979 Los Angeles. The Land South of the Clouds was awarded to 2017 National Silver Medal in multicultural fiction by the Independent Publisher Book Awards.

Smith has been teaching literature, composition, and creative writing at Louisiana Tech University for almost two decades. He is currently at work on the third book in his trilogy.

Interview:

Neil Connelly: Much of your work is set elsewhere/elsewhen, far from mainstream modern America. Can you share how setting in the broad sense influences your writing?

Genaro Kỳ Lý Smith: A good majority of my work is set in Vietnam more so than in America. I think artists, whatever medium they’re working with, owe it to themselves not to let places and experiences die. When I went to Vietnam and viewed Notre Dame Cathedral, or hiked two miles up a mountain to see the Perfume Pagoda, or rowed down the Perfume River; when I visited Sorrento, Italy and toured the Blue Grotto of Capri Island, I didn’t walk away and think, That was a wonderful experience. This vacation is great. I left knowing these places would make their way into my stories and poems. How can you, as an artist, not share just how illumined the blue water is inside the Blue Grotto? How can you let that memory die? I experienced it, so shouldn’t others who will never get to travel to Italy? Or what it’s like to row down the Perfume River, the boat parting the expanse of water completely covered by lotus flowers and lily pads? How, I ask myself, can any artist let those images, experiences die in the artist’s mind? By recreating these places on paper, I want people to be transported as though they were there themselves, and that’s one of the compliments I get from readers, that they felt like they were there.

Each of your two books, the novel The Land South of the Clouds as well as the long narrative poem The Land Baron’s Sun, were inspired somewhat directly by events in your life. When a writer fictionalizes reality, what are the benefits and how do they outweigh the risks? Why not just write nonfiction?

Each of your two books, the novel The Land South of the Clouds as well as the long narrative poem The Land Baron’s Sun, were inspired somewhat directly by events in your life. When a writer fictionalizes reality, what are the benefits and how do they outweigh the risks? Why not just write nonfiction?

What I’ve learned from John Wood is that you must tell lies upon lies to get to the truth. Tell as many until it reads like truth. The angle from which I approach any piece is not to tell what truly happened, because that would be journalism, but to tell what you wished would have happened instead. That’s fiction; that’s poetry. I don’t know if my grandfather Lý Loc’s youngest wife, Yen, came to the reeducation camp to spit in his face. But it’s believable if it evokes sadness and sympathy in the readers. I think when we fictionalize reality, it affords us the chance to reinvent our characters who are based on real people, say family members, or even us, the writers.

Too many times, and I mean every time, I get asked the same thing: how much of this is true? Did this really happen to you? Oh, you poor man, I had no idea. My aunt even texted me after she finished The Land South of the Clouds and asked if I was ever married to a Vietnamese woman before marrying her niece. Seriously. She thought I had been married before. But I did have a crush on Phuong, who was my “cousin,” and I’ve always wondered what could have been had our families still kept in contact, and so I revisited that part of my childhood, remembered my feelings for her, and brought our friendship to fruition.

However, there is some truth behind what we write and it stems from regrets and resentments more so than happy memories. The benefit of fictionalizing reality is that we revisit these memories, and however harsh or embarrassing or painful, it is those memories that entertain readers. We must lie and lie well in order to make the reader cry, or sigh, or slam their fists on the table in anger. You make them do that, then you’ve made them believe your lies are truths.

I was told by an audience member at a reading at the Maple Leaf Bar in New Orleans that my details, the objects that I use in my poems, are pedestrian. He went on to explain that it was not meant as an insult, but it was comforting: he enjoyed them because it was the everyday, mundane objects we use here in the U.S. are the same in Vietnam, so he felt like he was sitting at a kitchen table in Vietnam, or working in a garden using the same tools, or walking down a crowded boulevard careful not to get run over by motorists.

As a writer who enjoys such a rich and diverse cultural heritage, how much consideration do you give to audience? Put another way, do you feel like you’re primarily writing to mainstream America, showing them a world most never glimpsed? Or would you find more artistic satisfaction in that diverse reader who might see his/her own unique identity reflected in your pages?

I want to reach out to both types of audiences: mainstream America, and the diverse reader who sees his/her own unique identity reflected in my pages. But the definition of mainstream America to me has changed. In order to reach both audiences (mainstream America and the diverse audience) is through what I learned from Robert Olen Butler and John Wood: art must be universal. It took me so long to figure that out, but I finally got it. Everyone “yearns” for what is unobtainable. Everyone. It doesn’t matter where you’re from, what your race is, your religion or ethnicity or nationality. Everyone grieves, loves, worships (or not), and we all hate. The good people, the ones who are accepting of others try not to hate, but that is a universal trait as well.

You take Adam Johnson’s The Orphan Master’s Son set in North Korea, and the agents and soldiers have strict orders to carry out under the watchful eye of “The Great Leader,” but they pine for human connection. We do too here in America. The immigrants or refugees who came here and are still coming here pine for human connection and to be treated and viewed as people deserving of this thing called life. All of us have had that in-suck of air caught in our throats because we don’t want certain restraints placed upon us, we don’t want to feel rejected. These are all universal feelings. Mainstream America understands it; the diverse audience understands it.

I’d like to close by flipping the roles a bit and ask you to put your writer persona to the side. Reflecting on your formative years, do you recall when you had the experience you just referenced? That is, when did you see yourself reflected in stories, film, or anywhere in the culture around you?

I’ve always loved films, always. I’ve always had an affinity for 80s films, particularly John Hughes films like Pretty in Pink. I could identify with both female and male characters: the Molly Ringwald character attracts the attention of a student from a higher social class, but she is told it wouldn’t work out, but in the end, she gets her man. As well I identify more so with Ducky (Jon Cryer), who is interested in Molly Ringwald’s character, but of course, he loses her to the rich guy. Ducky is happy for her, that she triumphed regardless of her lower class standing. That has always been the case with me: losing someone I was dating to someone else, not because of money as is the case in the film, but because of my racial make-up.

Therefore, a film I identified with during my formative years was Map of the Human Heart. It is about a half white, half Aleut who falls for a woman who is also biracial. They grew up in an orphanage, separated, and WWII brought them together again, and though they love each other, she chooses to marry a Caucasian man because “life would be better for her than to be with another half-breed.”

That was how it was for me: losing women to other men because they feared the looks, the name-calling, and any other forms of backlash. When I saw that movie, I realized my fate. Until, of course, at age 37, I was blessed when I found Robyn.

If you read the chapters “Beautiful” and “How Is Not Important” from The Land South of the Clouds, not much imagination was used. None. It is probably why those who read the novel have called or texted and said those two chapters, “Beautiful” particularly, were their favorites because they were gut wrenching and poignant.

Given the vantage point you now enjoy, can you pick a particular point in your development as a writer and offer advice back in time to your younger self?

It would have to be in my early 20s when several of my undergraduate professors told me stop using adverbs. I didn’t understand it then, but I do now. I think back to some of my earlier publications from that time, and cringe when I come across words like “quickly,” “slowly,” “immediately,” and think, What was I thinking? One of several important things I tell my students is show, whether it’s poetry or fiction, please “show” me a story as though I am watching it on the big screen or on television. Also, never sit down and give a page count. Never sit down and say, “This story is going to be ten pages long,” because what if at nine pages in it gets really interesting? Do you short change yourself and readers and wrap everything up by page ten? What if the story turns out to be novel or novella material, or even part of a cohesive short story collection? So I go into a short story not knowing if it’ll be a short story. It could grow into something I never considered.

What I would tell my younger self is not to resort to the “Band-Aid” technique, the self-inflicting practice of salvaging or hanging on to a story because it has one or two good sections, but the rest of it is complete trash, and so you try to patch up the “bruised” and “cut” and “gashes” that make up the majority of the story. But that never turns out successful. Instead, keep the one or two sections (whether it be a sentence, a paragraph or even a whole page) and throw the rest away. Rewrite from that one or two good sections.

So many young writers will not let go of the story they feel they’ve worked so hard on, and when they’re advised to throw it away, they become defensive to the point of being clingy. That was a sure way for me not to get published. I learned that there will be hundreds of pages I will write that no one will ever read, and it’s because everything from voice and tone, dialogue to narration, description to character development, and every other aspect of fiction and poetry are not working organically to form a cohesive whole.