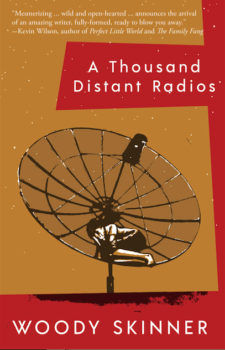

“If you’re not outraged, you’re not paying attention,” declares a popular bumper sticker. In his debut collection of short stories, A Thousand Distant Radios (Atelier26 Books) Woody Skinner’s characters can’t help but pay attention to a slough of modern-day threats: oil spills, dysfunctional families, thievery, poverty, traffic. But he arms them with something more powerful than outrage—he sets them in narrative. Story accentuates conflict but declares neither side the winner. Rather, for Skinner, it’s writing and reading that triumph: “[T]he pond robber . . . had been so stealthy and efficient as to seem made not of actions but words . . . . [H]e’d been an idea with dynamite.” Words are action, tasking us readers to wonder at the whole tale, at all sides involved, including our own. What are all of us up against? How are we subjects of our collective drama?

Skinner plays with subject-hood. The expectant dad in “Atlantic Blue,” a photographer whose name we never learn, says, “I, on the other hand, was born for sad subject matter.” When he learns he and his wife are having a baby fish, he builds a custom tank and hangs a mobile in its salt water. When paint floats off the mobile’s metal objects, this dad and his wife run for their cameras. The effect, although toxic to their new fish, is too beautiful not to capture on film. Skinner’s characters swim in destruction. They bathe in it. They’re victims and viewers of their own contemporary art.

Skinner plays with subject-hood. The expectant dad in “Atlantic Blue,” a photographer whose name we never learn, says, “I, on the other hand, was born for sad subject matter.” When he learns he and his wife are having a baby fish, he builds a custom tank and hangs a mobile in its salt water. When paint floats off the mobile’s metal objects, this dad and his wife run for their cameras. The effect, although toxic to their new fish, is too beautiful not to capture on film. Skinner’s characters swim in destruction. They bathe in it. They’re victims and viewers of their own contemporary art.

TV figures prominently in A Thousand Distant Radios. Often on in the background, its meaning is foregrounded, reflecting our contemporary distance from ourselves. We’d rather look out than in. Skinner compels us to do otherwise. When the narrator’s dad dies in “Preferred Signals,” he crawls into the satellite dish his dad put up so they could watch cable in backwater Arkansas. Or look at the TV distractedly, so as not to look at each other. The real drama is not on the screen but on the page—between dad and son and a girl they both love. In “Things in Slow Motion,” “we,” the workaday townspeople watch “you,” a doctor, with his “steady detachment” as his life spirals out of control. Who gets the last word when “our presence gives you a lonesome kind of comfort”? We readers are part of the composition, omniscient, both “we” and “you.”

These aren’t voyeuristic peeks into messed up lives. Skinner’s empathy is palpable. In “Weight,” together with Nikole, celebrating her sixteenth birthday with her boyfriend in his “hunting club,” we “swallow the world’s offer of disappointment, consume it eagerly, even.” Desire and tension dignify these downtrodden characters and make them relatable. With humor and satire, Skinner thumbs his nose at the chaotic existence with which we’re all familiar. In “Summering,” Penter, whose girlfriend leaves him for not caring enough, cares so much for his consoling neighbors that he gives them a fish that ruins their pool water.

We can’t win, but we won’t lose, either, with Skinner to tell the tale.