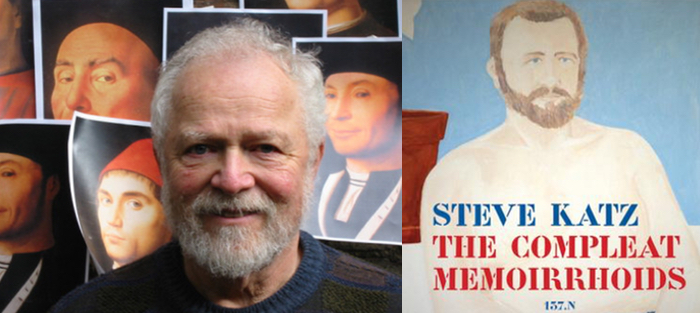

Ten years ago, I wrote the following essay [originally published here on October 12, 2009] in response to a conversation I’d had with Steve Katz. Katz, who died August 4, 2019 at the age of eighty-four, was a larger-than-life figure in the experimental fiction community. Early in his career, he published with big New York houses: The Exagggerations of Peter Prince (Holt, 1968—yes, the extra g in the title is intentional); Creamy & Delicious (Random House, 1970); and Saw (Knopf, 1972). Katz was there at the foundation of American postmodernism, and indeed helped lay it foundations.

But Katz lived by the advice he gave me, and kept reinventing himself as a writer. He left the big houses to co-found the original 1974 Fiction Collective, dedicated to author-centered publishing against the grain. This eventually morphed into Fiction Collective 2, which is arguably America’s most significant publisher of category-defying fiction; FC2 has published authors as varied as Samuel Delany, Brian Evenson, Diane Glancy, Fanny Howe, Stephen Graham Jones, Michael Martone, Lance Olsen, Diane Williams, and Lidia Yuknavich.

Katz went on to publish with these collectives through the bulk of his career, as well as releasing a trilogy of novels with Sun & Moon Press: Weir & Pouce (1984), Florry of Washington Heights (1987), and Swanny’s Ways (1995). He wrote poems and screenplays and many things uncategorizable. He closed his career with the father/son novel Antonello’s Lion (Green Integer, 2005), the story collection Kissssssssssss (FC2, 2007), and a series of essays—the first of a longer project—called The Compleat Memoirrhoids (Starcherone Books, 2013).

Though I was never Steve Katz’s student, he took me under his wing in the late 1990s while I was at the University of Colorado-Boulder, where he taught and for a time ran the graduate creative writing program. We got together to talk about writing, usually at an old-fashioned newsstand/coffee shop near his home in Denver’s Capital Hill district that I can’t find on Google maps anymore. We kept in contact for twenty years, though I didn’t get to see him much toward the end because a teaching job took me away from Colorado. But the older I get, the more important it feels to me to keep his spirit going and never stop reinventing.

It’s hard enough when the world pigeonholes you, I can imagine Steve saying in his deep, burly voice, gruff with the residue of New York’s outer boroughs. Why would you ever want to pigeonhole yourself?

I miss Steve Katz, and I hope you’ll read him so the writers of the world will remember him the way he should be remembered: as a fearless sailor willing to float wherever the current of words took him. R.I.P., Sir.

“Every book I publish is an opportunity for me to reinvent myself as a writer.” — Steve Katz

If you look for this quote in any print or electronic source about Steve Katz, you’re not likely to find it…unless someone was spying on our conversation at the French restaurant Le Central in Denver about a year and a half ago. Steve Katz has been publishing fiction for as long as I’ve been alive—he has been widely acknowledged for decades as a grand wizard of innovative form, though he is so much more than that—and I sought him out because on the eve of my first book’s publication, I was panicking. The voice that told me This is your big break and you have to capitalize on it! competed with the one that said Now you can write what you really want to write! and the one that said Now you can get a better teaching gig! There were a lot of voices, all telling me what to write about and think about next, and I felt paralyzed. I couldn’t write a line without thinking about where I could publish it and how it would best serve my careerist interests. I felt like a fraud, like a non-writer who had just happened to cobble a book together and con a few people into liking it.

So I called Steve Katz, because he has been through all the writerly wars. We sat down for lunch at Le Central, and he listened to my scattered diatribe about how conflicted I was. Then he looked up, finished chewing, and very calmly spoke the words that form the basis of this column. I’d like to say that the effect was immediately calming, but in truth I kept whining all through lunch about how indecisive I felt. When I got home, I let my mind continue to cycle through its relentless, non-productive orbits. It took a while—long enough for the ego roller-coaster of Wifeshopping’s actual release to settle and reverberate—to absorb what Katz told me and think about what it meant.

So I called Steve Katz, because he has been through all the writerly wars. We sat down for lunch at Le Central, and he listened to my scattered diatribe about how conflicted I was. Then he looked up, finished chewing, and very calmly spoke the words that form the basis of this column. I’d like to say that the effect was immediately calming, but in truth I kept whining all through lunch about how indecisive I felt. When I got home, I let my mind continue to cycle through its relentless, non-productive orbits. It took a while—long enough for the ego roller-coaster of Wifeshopping’s actual release to settle and reverberate—to absorb what Katz told me and think about what it meant.

The easy thing to do when we finish one writing project, the default thing, is to simply think about what we’re going to write next. Katz’s words, however, call us to engage in a deeper kind of reconsideration of ourselves, because what we write and who we are as writers are two crucially different things. It’s convenient to not pry open the Pandora’s Box of the who we are question, since it’s sticky and can potentially derail us from all we hope to accomplish. But if we simply move from one project to the next, tacitly assuming a static writerly identity that we do not question, then we may miss out on our best chances to set new challenges for ourselves and grow. This principle can apply not only when we publish books, but when we move from project to project.

This isn’t to say that we shouldn’t think about what to write next, because that’s completely natural. We all have our books-in-planning, and many of us have projects that we rotate through like crops in a field. The momentum that brings us from one project to another is more likely to move us forward as writers than merely stopping and thinking about the who am I question, which does very little in a vacuum. (I can imagine few things more frustrating than being forced to contemplate my writerly identity in the absence of any real work.) But without taking the time to step back and ask myself why I’m embarking on my next project, I feel like I’m taking the same approach to my material that I’ve always taken before, and in some way writing the same thing over and over again. The material alone does not determine how our fiction turns out; it’s also affected by our relationships to the material, to our readers, to our habits of mind as we work. Beyond our subject matter itself, we have quite a few other things to consider when we take a step back and re-invent ourselves as writers.

Our work habits and how we feel about them.

Transitional points are great times to think about the nuts and bolts of what we do. Sometimes we put more pressure on ourselves to produce, and other times we forget about producing and try for a greater sense of freedom. Both impulses can alter our work habits, sometimes simultaneously. After Wifeshopping, I took a break from short stories and threw myself into a novel, pressuring myself to work through my drafts more quickly so that I wouldn’t have to hang so long in the limbo of incompleteness. But I also started doing my re-writes from scratch, which I had typically avoided. This combination of habit changes gave me much more control and flexibility with the narrator’s voice than I’d ever had before. A small change in approach allowed me to find a way to write this book at this particular time, and I know that my old work habits would not have done the trick.

Our relationship with our readers.

We have readers, real or imagined, and between projects or publications is a great time to re-evaluate how we interact with them. Real readers can tell us a lot about the habits and themes that we don’t know about (such as the one who pointed out my deep interest in secondhand clothing and bric-a-brac) and bring them to the surface so that other subterranean interests can emerge. Simply having people who don’t know us respond to our work can—especially if it’s a new experience—put the reader/writer dynamic into sharper relief. After I toured around a bit I had a new appreciate for how willing readers were to invest in the emotional uncertainty of fictional characters, and knowing that gave me permission to dig down into new layers of uncertainty that I’d never been sure readers would be able to appreciate. This reader dynamic also includes support networks and how we use them. Do we show work to our first readers earlier in the process? Later? Do we add to or distill our group of early readers? For those who are coming out of workshop situations where readers are built into the program, this can be a particularly useful private conversation to have.

Our relationship to our traditions.

We all come from somewhere, and typically we learn more about where we come from the longer we stick to our writing path. It’s up to us to decide whether and how we interact with our traditions on the page, as well as which traditions we’re going to engage in our next phase. No writer is a product of a single tradition, and no tradition can be taken on without some degree of self-knowledge, so we have plenty of choices to make: challenge our old traditions, embrace new ones, engage in conscious homage, etc. We may have some traditions that we haven’t explored fully, and some that we have temporarily tapped out. If “we are what we eat” in the creative sense, then some thought to what we take in as readers is central to our writerly identities.

Our relationship to the publishing world.

Unless we lead a purely literary life, unpolluted by thoughts of the market, considerations of where we publish and how we pitch ourselves to the world are going to enter our psyches. Since they can affect our sense of who we are as writers much more than what we do on the page—tapping, as they do so well, into our sense of self-worth, success, and failure—acknowledging them, rather than letting them creep stealthily into our decisions, is a good idea. We want to make sure that we consider such things at appropriate times, though. Transforming a literary homage to La Traviata into a “more commercial” metafictional detective novel in mid-draft might crash the project forever, but there’s nothing wrong with doing that when the work isn’t actually under construction. Similarly, we decide whether it’s a good time to hold our work back from periodical venues, try only for those we most want to be part of, or publish whatever we can, wherever we can. All of those approaches will probably have their seasons for us, and how we choose to move between them will tell us as much about our writerly identity—whichever incarnation we happen to be in at the moment—as what we do at the privacy of our own desks.

Unless we lead a purely literary life, unpolluted by thoughts of the market, considerations of where we publish and how we pitch ourselves to the world are going to enter our psyches. Since they can affect our sense of who we are as writers much more than what we do on the page—tapping, as they do so well, into our sense of self-worth, success, and failure—acknowledging them, rather than letting them creep stealthily into our decisions, is a good idea. We want to make sure that we consider such things at appropriate times, though. Transforming a literary homage to La Traviata into a “more commercial” metafictional detective novel in mid-draft might crash the project forever, but there’s nothing wrong with doing that when the work isn’t actually under construction. Similarly, we decide whether it’s a good time to hold our work back from periodical venues, try only for those we most want to be part of, or publish whatever we can, wherever we can. All of those approaches will probably have their seasons for us, and how we choose to move between them will tell us as much about our writerly identity—whichever incarnation we happen to be in at the moment—as what we do at the privacy of our own desks.

It’s worthy to note that Steve Katz, who spoke the words I now extrapolate from, is in his early seventies. That’s a lot of years of re-invention, and it argues for a Trotskyite approach to one’s literary identity: perpetual revolution and continued openness to flux. Each project demands different things from us as writers, and it’s easier to meet those demands if we keep changing the writers we are. We’ll never write the same book twice, because we’ll never be the same writer twice—unless of course we don’t open up that Pandora’s Box and think about it, in which case we may end up being the same writers for a lot longer than we want to.